When was the term “wangmin” coined, and how did China’s cyberspace evolve from the first-generation of netizens to today?

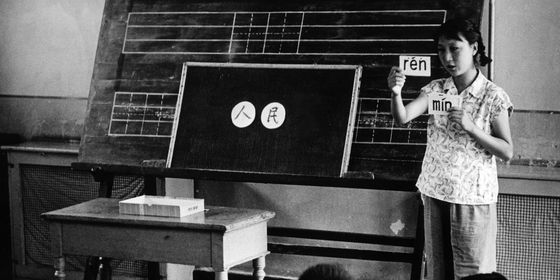

If you are reading this on any internet-surfing device, then July 8 is a special anniversary for you: On this day in 1998, the China National Committee for Terminology in Science and Technology (CNTERM) introduced the term wangmin (网民, “netizen”) to refer to the country’s fast-growing population of internet users, forever changing the way publications like TWOC have referred to public opinions in China.

China officially connected to the Worldwide Web just four years earlier, in 1994. This had opened a new window on the outside world for many Chinese. Li Jia, a 54-year-old sales manager from Guangdong province, was one of China’s first-generation wangmin who surfed the internet when it was still a novelty in the country. At the time, he had just graduated from college and taught physics in a middle school in the Pearl-River Delta Region in Guangdong.

Back then, when Li wanted to surf the internet, he first needed to dial his Internet Service Provider in Guangzhou, and then wait for his modem to connect to the websites of Chinese FidoNet (CFido). "It usually took at least 10 seconds to connect to the internet," Li recalls to TWOC. Sometimes, the lines were busy and he would set up auto-dialing on his modem. "While waiting for the connection, I would leave to do other things or play single-player video games on my computer. When the modem 'screamed,' it meant the internet was connected, and I would rush back to my computer."

Many first-generation internet users shared their experiences similar to Li’s. Since the telephone lines were usually busy during the day, they would stay up late at night to go online. Due to the high costs of internet usage, most netizens connected with one another on limited networks such as BBS (Bulletin Board Systems), the most popular online platforms at that time.

Not all internet users could afford a personal computer. A 486 computer, the most advanced at the time, cost over 9,000 yuan in 1995, and the average annual salary in China was around 5,500 yuan. Internet cafes were also still rare, and usually charged customers 12 to 15 yuan per hour to surf the net (for reference, a kilogram of pork cost 14 yuan at that time). An early internet user called Yan Yong told Science Daily newspaper that he’d saved two days’ worth of food money in order to surf the net in an internet cafe when he was a college student in 1996.

Although the connection was slow (56 kbps, compared with the usual speed of 100 mbps and even 1,000 mbps today) and most users could only communicate in words on BBS, as it would take up too much time and traffic to upload images, surfing the net was an extraordinary thrill for wangmin at that time.

“On BBS, you can find a lot of information and download useful materials you have never seen before,” said Li. He can't recall the names of the BBS and sites he visited back then, but remembers their clunky design. "There were different discussion forums where you could download software programs shared by other netizens, as long as you were willing to spend the money, since the download would use up more traffic [and cost more]," he says.

As more and more people came to know about and adopt the internet, the group of users continued to expand in China. From 1996 to 1998, in just two years, China's internet users surged 20-fold from 100,000 to 2 million. Many of these first-generation netizens were active members or even administrators of various BBS, who, like Ding Lei (founder of NetEase) and Ma Huateng (founder of Tencent), were among the first to foresee the huge internet market in China, and later set up business empires that indelibly shaped the Chinese internet landscape. It was also during this period that the three major web portals in China—NetEase, Sohu, and Sina—were established. The internet giant Tencent, which later created instant messaging tools like QQ and WeChat, was founded at the end of 1998.

In response to the growing population of wangmin, the CNTERM felt the need to offer a Chinese term for the group, among 56 new terms related to internet technology. According to a report published by the state-run China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) in 2008, the term wangmin was defined as “Chinese citizens aged 6 years and above who have used the internet within the last six months.” The CNNIC also offered another definition for wangmin as those who “use the internet for one hour or more per week.”

When netizens reshaped Chinese society

As Chinese society entered the millennium, the number of netizens in China had surpassed 20 million, 10 times more than that in the late 1990s. This included Li Jia’s 11-year-old daughter Li Huitong. When Li Huitong was in the fourth grade in primary school in 2004, Li Jia helped her register a QQ account, making his daughter one of the first millennials to access the internet in China.

Outside of China, the rapidly increasing population of netizens started to reshape the world. In December, 2006, Time magazine chose “You”—the creators and consumers of user-generated internet content—as its "Person of the Year,” a move that recognized the growing significance of the online community. Before this, social network and content-sharing websites like Facebook had launched in 2004, YouTube in 2005, and Twitter in 2006.

Three years later, the Twitter-like social platform, Sina Weibo (now usually just called Weibo), was established in China, at a time when the number of netizens in the country had exceeded 250 million and ranked first in the world. Since then, Chinese netizens have used Weibo as a forum for staying up-to-date on news and trendy topics, and participate in public discussions.

It was also in 2009 that netizens managed to influence the outcome of several high-profile news incidents. For example, Deng Yujiao, the pedicurist in Hubei province who stabbed to death a local official who tried to rape her, was released on bail and later charged with assault rather than murder after her case generated more than 4 million forum posts on the internet. Netizens decrying the corruption of officials, and even distributed T-shirts supporting Deng on the internet.

Similarly, netizen opinions overturned the conviction of Sun Zhongjie, a company driver who gave a lift to a seemingly stranded stranger who then revealed himself to be an undercover police officer and arrested Sun for operating an unlicensed taxi. The 18-year-old Sun had cut off his pinkie finger to protest his innocence, and his case started an online debate on other incidents of “entrapment (钓鱼执法)” by law-enforcement officers. During this period, people optimistically believed in the power of netizens to lead public opinion and promote social progress. A famous slogan from the era summarized this attitude: “Attention is power, spectatorship changes China (关注就是力量,围观改变中国).”

The development of regulations related to netizens

But as the internet environment became more complex, and online users more active, the government started to introduce and strengthen cyberspace regulations. In 2014, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), led by the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission, was founded. Since then, it has enacted a series of laws and regulations aiming to “clean up” online content and ensure cybersecurity, including the Cybersecurity Law (2016), the Provisions on Ecological Governance of Network Information Content (2019), and Provisions on the Administration of Internet User Public Account Information Services (2021).

Among these regulations, one of the most significant changes for Chinese netizens is the implementation of real-name registration. As of 2017, all internet users are required to provide their phone number, which is linked with their legal name and ID number, when creating an account on Chinese websites. When using online payment and playing video games (with authorities aiming to curb excessive gaming by minors), one may be required to provide further real-name authentication by submitting a photo of one’s ID card, or even facial recognition.

The content that internet users publish or spread online was further restricted starting from 2021, as new rules stated their accounts could be temporarily or permanently closed if they publish something that violates state regulations.

Li Huitong has clearly felt the changes. In 2016, she graduated from university. Gradually, she found that she could not log on use email, QQ, WeChat, Weibo, and other services unless she bound her phone number to her account. These days, she is asked to authorize they use of her phone number even before ordering food in a restaurant using a QR Code.

“Sometimes, I am worried where my data has been sent and who might follow my everyday activities,” Li Huitong tells TWOC.

Although she has not encountered problems using her social accounts so far, she knows of friends and bloggers whose accounts have been banned due sharing opinions that apparently violated rules on various platforms. She has also become used to seeing content frequently deleted online.

“It is much harder to have public discussions online now, as we can’t get the real information. Sometimes, when I go to read an article that was published just 30 minutes ago, I find that it has already been deleted,” says Li Huitong.

Chinese netizens in a new age

Despite the regulations, the number of Chinese netizens continues to grow. In 2018, China was home to one-fifth of the world's internet users. By December 2021, the number of internet users in China has exceeded 1 billion, amounting to 73 percent of the whole country’s population.

The internet landscape and netizens’ activities are also more diverse compared with that of 30 years ago. As the 49th “Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development” published by the CNNIC in February 2022 shows, the top three online activities of Chinese wangmin are instant messaging (done by 97.5 percent of netizens), watching online videos (94.5 percent), and watching short video (90.5 percent). More than 80 percent of netizens shop online, and more than 50 percent order food online, while 40 percent use online ride-hailing services.

The internet market has continued to grow under the Covid-19 pandemic, as more people are working and studying from home, and are relying more heavily on online applications and contact-free services. As shown by the CNNIC’s statistics, in 2021, netizens who worked out-of-office grew by 35.7 percent, and those using online medical services grew by 38.7 percent compared to the previous year.

Notably, as online education has been rolling out from kindergarten to high school amid the pandemic, minors today are accessing the internet at a younger age compared to their predecessors. China's underage internet users have now reached 183 million. The rate of internet penetration among under-18s is 94.9 percent, much higher than the figure for adults (82.4 percent).

On the other side of the demographic spectrum, 119 million senior citizens aged over 60 were online as of 2021, accounting for 11.5 percent of the netizen population. The number of this group continues to grow against the backdrop of pandemic prevention and management. According to the CNNIC, the first year of the pandemic witnessed a growth of 80 million new internet users, many of them seniors who had never used a mobile phone before, largely due to the widespread use of health QR codes in Chinese society.

Toward a better cyberspace?

Today, Chinese netizens spend 28 hours online on average per week, or four hours per day. The portrait of Chinese netizens has changed dramatically from the CNNIC’s definition of wangmin in 2008—“Chinese citizens aged 6 years and above who have used the internet within the last six months” or “for at least one hour per week.”

Now in his 50s, Li Jia finds himself even more “addicted” to the internet than in his younger years. He shops for almost everything online, except fresh groceries, and receives at least one parcel per week from online shopping. He also plays video games on his smartphone whenever he is free—no longer having to stare at a desktop computer and wait to dial up.

Although he thinks the cyberspace of his youth had its good points, he feels that things are better now. “It was expensive and difficult to connect to the internet in our time, so we cherished every opportunity to surf online. The way we communicated online was concise, and the information we got from others was usually helpful,” Li Jia said. “But in general, life is more convenient with the benefits and progress of the internet today.”

As a millennial, Li Huitong has more ambivalent feelings about the new changes in cyberspace. Recently, she became worried about a new rule introduced in May for Chinese netizens: In order to discourage “bad behavior” online, a number of Chinese social platforms, including Weibo and WeChat, have started displaying user’s geographic location based on their IP address when they post or comment in the platforms to discourage “bad behavior” online.

But as a netizen who has seen cyberstalking happen to several bloggers she followed in the past, Li worries that this rule might worsen the leakage of privacy and even threaten the personal safety of netizens, especially female netizens like her.

“Of course, internet technology has progressed a lot. But I think we are still far away from creating a better cyberspace for Chinese netizens,” says Li Huitong.

Li Jia and Li Huitong are pseudonyms