More than street snacks and brewpubs, Beijing’s hutong demolitions marks a twilight for traditional crafts

The scent of lamb chuan’r wafts up from BBQ stalls and hangs over the narrow alleyway, sweet and smoky. Groups of diners sit on low-slung plastic stools by a mountain of discarded skewers, now and then erupting with peals of laughter. Rowdy drunk chat, the clink of empty bottles, and other chaotic and familiar street scenes are being reminisced over as the Beijing government’s gentrification campaign hit the city’s hutong this past spring.

But these networks of historic alleyways are not only home to disappearing siheyuan, hip craft-beer joints, and the elusive yellow weasel. Though most aren’t likely candidates for any World Intangible Heritage Lists—and official clean-ups have put an end to illegal construction (offering a quieter life for the remaining residents)—the city’s vernacular handicrafts and pasttimes are struggling to survive the nosy process of modernization.

Here, TWOC profiles four of the last preserves of this dwindling culture.

Traditional Paper-Cutting

The once-residential courtyard home (siheyuan) is now a brewpub. But just down the street, a crowd of children gather under the halo of an orange street light, watching an old man on a saddle stool cutting shapes from a sheet of red paper. He works silently and from memory; onlookers appreciatively murmur as they watch the unerring movements of his sharp knife. He unfolds his creation and the crowd applauds. It’s a rooster motif, made with a paper-cutting technique that dates back to the second century.

Zhang Yonghong once owned a successful paper-cutting art shop in Nanluoguxiang’s Ju’er Hutong. For two years, footfall was high, and the passing trade was enough to keep the shop open, and even pay for treatment of his daughter’s congenital brittle-bone disease.

According to entertainment website Xingzuo360, “Chinese folk paper-cutting embodies the country’s rich historical culture, folk customs and traditions, and regional cultures [and] reflects the colorful special characteristics of Chinese culture.” They are particularly important during Spring Festival, when people hang motifs of the year’s zodiac animal on windows and doors. At weddings, well-wishers paste paper-cuttings of the “double happiness” character on the walls of the ceremony rooms, wishing the couple luck.

When his landlord raised the rent, Zhang was pushed out of his hutong and forced to move south, to the quieter Chaodou Hutong, where he has lived for the last three years, sleeping in the back of his shop.

There are fewer tourists here, and Zhang relied on friends’ support and donations to stay open. But in the end, he had no choice but to send his daughter to Shaanxi to live with her grandparents.

Pigeon keeping

On May 9, 2017, a Sohu blogger detailed a bloody massacre occurring in a soon-to-be demolished hutong.

Carrier pigeons (信鸽) that would normally fetch hundreds or thousands of RMB in the collector’s market were being practically given away. Breeders of the birds, bought to enter races or shows, were desperately seeking to get rid of their stock before relocating to an apartment complex by the month’s end. Some could be had for 40 RMB apiece. Any that couldn’t be sold or given away were killed.

Hutong pigeon-breeding is rumored to date from the Eight Banner Armies, allies of the Manchu invaders in the 17th century, known for sending military communications by pigeon. After the establishment of the Qing Dynasty, Manchu allies were permitted to live in in the Inner City of Beijing (where most of the city’s remaining hutong are) and continued to raised the birds for recreation, until the alleyway aviary became one of the symbols of Old Beijing.

Periodic pigeon culls have taken place in the past, mainly over sanitation and avian flu concerns. But as Chinaxinge.com, a news portal catering to pigeon hobbyists, noted in 2016, carrier pigeons are becoming extinct in Beijing.

Traditionally, breeders release their birds out to exercise twice a day at dawn and dusk (a practice that Peking Opera master Mei Lanfang called “exercise for the eyes, so one wouldn’t become nearsighted”). Now “skyscrapers and power lines cut the sightline to pieces, making the birds bound hands and feet by the broken sky.”

Relocations play a role too. “With apartment complexes, one has to think about one’s neighbors, so pigeon-raising is on the decline,” a breeder surnamed Liu, soon to be relocated after 30-years of pigeon-raising in the hutong, told Sohu. He and his neighbors are loath to massacre their flocks, particularly the chicks, but face a demolition deadline—and a dwindling habitat for both themselves and their birds in the city, even if they could manage to give the pigeons away.

Street Food

Beijing’s hutong are rich in food culture. Yet the “renovations” have also shuttered many restaurants, especially the affordable and open-air variety. “One of our favorite fermented mung-bean milk stalls fell victim…the locals who live in the hutong are devastated,” Jamie Barys, CEO of UnTour Food Tours, told TWOC.

Meanwhile, hutong that receive government support for conservation have become “‘Disneyfied’…misrepresenting the local culture in order to provide a more commercialized area that can cater to tourists and their pocketbooks.” Barys added that “finding places that are not under threat of being bulldozed, but are [also] still home to locals, is becoming increasingly difficult.”

The government point to the necessity of the changes, especially regarding food safety. At the start of National Food Safety Publicity Week, Yan Jiangying, the Director General of the Information and Publicity Department of the China Food and Drug Administration, argued that “with the rapid evolution of the industry, food safety management has become a complicated cause that requires the concerted effort of the government.”

Speaking at the same event, Chinese Vice President Wang Yang emphasized the community aspect of the problem. Xinhua reported that Wang “urged local government, enterprises and the public to work together to ensure food safety.”

Yet not all are convinced by the licensing and food safety arguments. The Economist reported on several businesses that were “up to date with all [their] paperwork” and had “passed inspections for years,” but were “mysteriously declared to be illegal” when the renovations started.

Barys agreed that “the unclear government regulations seem to leave residents and business owners with the most confusion. No one knows when rules that have been lax for decades will suddenly be enforced.”

Al fresco eating in a Beijing alley (ifeng.com)

Oscar Holland, a former editor of That’s Beijing magazine, claims that the government’s actions were financially motivated. “If you follow the money trail, you’ll find that small businesses and shops make about 30 percent of the city’s GDP, but they’re only contributing 7.5 percent of the tax. So it’s not particularly beneficial to have small businesses operating there,” Holland told SBS.

The BBC’s Stephen McDonell also argued the “renovation” had an economic angle, and said that most of the owners of small bars and eateries are economic migrants who do not hold the correct hukou (household registration document), and thus operate of the fringes of legality. McDonell described the government’s actions as “tidying up the neighborhood.”

Architecture

Some citizens and NGOs have taken the matter into their own hands. In 2010, the Telegraph reported that conservationist protests against the redevelopment of the historic Gulou area—whose main attraction is a pair of Ming-era (1368-1644) Drum and Bell Towers—saw initial plans to building a shopping plaza shelved.

NGOs such as the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center (CHP) have been working on projects that assess the state of the hutong areas since 2006. The group also collaborates with local residents, developers, and architects to share expertise and appreciation for traditional architecture.

To the east of the Forbidden City lies historic Shijia Hutong. Half way down is the No. 24 siheyuan, one of the beneficiaries of CHP’s efforts. In 2013 the courtyard was expertly renovated with 5.3 million RMB ($78,000) from the Prince’s Charities Foundation China and the local municipal government, and turned into the Shijia Hutong Museum. The building feels like a bubble stuck in time, as sound recordings of Old Beijing echo off the smoke-gray walls.

But the austere and sterile surroundings of a museum are no substitute for the real, dusty, natural and imperfect city. Barys told TWOC he believes that “the design of the hutongs influences so much of the city’s intangible cultural heritage.” To him, “they are more than just buildings—they represent an entire way of life.”

In this sense, the hutong problem—the unanswered question of conservation: “renovation,” or redevelopment?—may best be understood as the difference between seeing an animal in a zoo and observing one in the wild. It is both the people and the hutong themselves, the winding and intersecting streets where you might bump into a friend and squat down for an impromptu beer, which imbue the city with its special character—a character that may soon exist in memory alone.

Hatty Liu contributed to this report

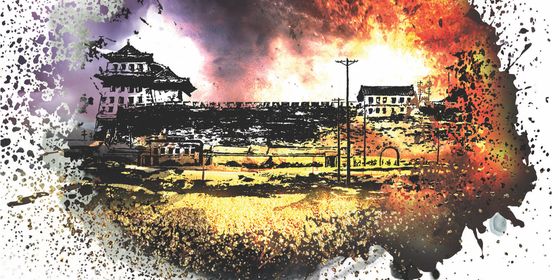

Cover image from ifeng.com