What do wacky bathroom signs have to do with political reform?

It’s widely known that paper was invented in China. Less widely known is that China also invented toilet paper. But while China has contributed much to world history in the realms of both printing and pooping, it has preferred to keep some toilet things to itself.

Toilet propaganda is one of these things.

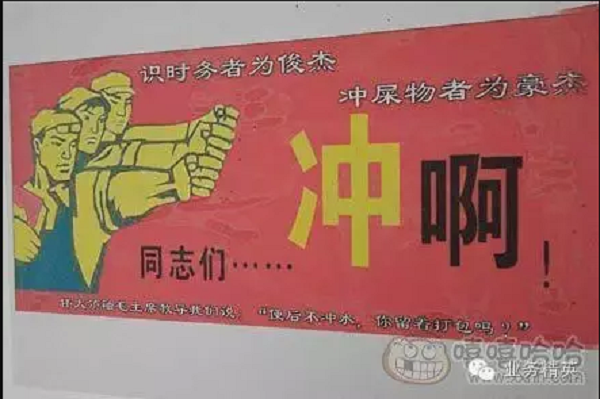

“Comrades, flush!” (WeChat)

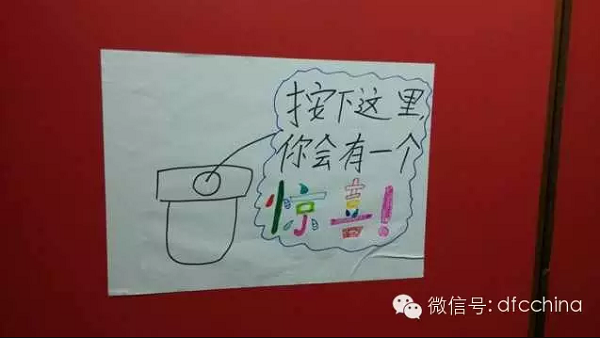

In 2014, third-graders in Class One at Shenzhen’s Nanshan Experimental Elementary School embarked on a quest to solve their school’s toilet troubles by, among other things, creating hand-drawn signs and slogans. Hitherto, many children and parents had complained about bad smells and poor sanitation in the school’s bathrooms, with lack of flushing and toilet paper littered on the floor. With markers and construction paper, the students created illustrated slogans and short stories teaching the moral of “increasing one’s civilized toilet consciousness.”

“Press this and you’ll get a surprise!” says handmade toilet sign courtesy of Shenzhen third-graders (WeChat)

Toilet sanitation problems, nor the school’s solution to it, aren’t particularly Chinese—in bathrooms the world over, there are probably small reminders about flushing and turning off taps. But like socialism, debt, aircraft carriers, and many things, these signs are not without Chinese characteristics. They are not simply bathroom bulletins but biaoyu (标语), a type of educational sloganeering related to political and social reform in Chinese history.

Originating as a form of political resistance towards the end of the Qing Dynasty, biaoyu are short slogans with simple language and concise meanings, generally distinguished from corporate slogans by the fact that they’re meant educate or give ideological encouragement. Sometimes conflated with kouhao (口号), or spoken slogans, biaoyu aren’t necessarily chanted, but employ elements like rhyme, repetition, and wordplay that make them easy to remember and say.

Biaoyu served a variety of purposes throughout Chinese history. In 1905, reformers of the Tongmen Society had 驱除鞑虏,恢复中华,建立民国,平均地权 (“Drive out invaders, revive Chinese civilization, build republic, equalize land ownership”), which later became Sun Yat-sen’s Three Democratic Principles. TWOC has also previously compiled PRC slogans that cheered on the nation from the Great Leap Forward to the modern day. Wenqian Kouzhu, in an article about biaoyu for Modern Chinese magazine writes, “whether the New Culture Movement, the Agrarian Revolutionary War, civil war, or the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, during the political struggle of one group opposing another group, slogans have always become real weapons.”

Chinese philosopher Hu Shih, who died in 1962, once wrote “our China has already become a world of slogans.” Today, slogans are everywhere, painted on houses to extol the Family Planning Policy (in rural areas) or demolitions for urban development (in cities), written on signs to deter crime, and hung on banners on college campuses during holidays. Xiang Debao a communications scholar at Shanghai International Studies University, has written that “slogans have already become a type of unique Chinese culture, become a formative part of the Chinese nation’s collective identity, have become China’s quintessential quintessence.”

Therefore, in honor of World Toilet Day, TWOC has ventured among Chinese urinals to bring you the world’s first investigation into the meaning behind the words in Chinese restrooms.

While China is infamous for its sometimes sloppy English translations, many biaoyu are as odd in their original language. An English translation that reads, “You can enjoy the fresh air after finishing a civilized urinating,” for example, in Chinese says, “Be civilized when using the toilet, and nature will be pure and fresh.” The sign “Urine into the pool you short; The urine to the pool you soft,” says “if your pee doesn’t reach the bowl, it means you’re short; if you pee outside of the bowl, it proves that you’re flaccid.”

You wish this was mistranslated (WeChat)

Actually some of the wildest 厕所文明标语 (literally, “toilet civilization slogans”) aren’t even given translations. Signs such as “don’t pleasure yourself” leave it up to the non-Chinese speaker’s imagination to try to figure what could be meant by a blue elephant with his trunk around his penis. Signs like “this is something that I’ve always wanted to talk to you about: urinate into the bowl; the civilized you is the most beautiful” only give non-Chinese speakers a picture of a peeing stick person and the English words “this is what I’ve always wanted to talk to you.”

My personal favorite is “take one small step forward and civilization will take one large step forward.” This is exactly the kind of curt and clever wordplay characteristic of Chinese slogans from those in the street about “Comrade Xi Jinping” to those in the stalls that say “comrades, flush!”

Slogans in China are, in fact, valued as exemplars of good writing due to the difficulty coming up with a concise, cleverly worded message. In many high school literature classes in China, students will be graded on the quality of slogans that they write out on tests. Even for civilized toilet slogans, there are articles comparing the effectiveness of certain slogan phraseology over others in getting men to properly pee in the toilet bowl.

Some signs also reach into the past to give their biaoyu some extra Chinese characteristic: See the sign below, which plays on double meaning from a quote from the I Ching. Others use classical Chinese duilian (对联, antithetical couplets), including those written by famous Chinese artists like Xu Beihong, to encourage toilet-goers to maintain a good restroom environment.

“Gentlemen wait for the right time to deploy the hidden weapon” – the I Ching (WeChat)

The authors of most of these slogans though may forever remain anonymous. It may never be known who exactly came up with such toilet civilization classics as “come in a hurry, leave in a flush” or “cherish the facilities, save water” (which sounds much more poetic in Mandarin—lai ye cong cong, qu ye chong chong, and ai hu she bei, jie yue yong shui respectively).

However while no attribution may be given to these lavatory literary works, which can be downloaded and used online for free or requested on websites like Sogou Wenwen and Baidu Zhidao, the next generation of toilet civilization slogan writers is being raised out of the swirling waters.

Even at Tsinghua University, students are slathering the toilet stalls with self-made slogans. In one of the country’s most prestigious universities, short messages above the toilets encourage users to “trust me then give me a hug” or “cherish today which is the youngest day in the rest of your life.” These slogans and their accompanying illustrations, not created with toilets specifically in mind, are the works of the winners in the biaoyu category of Public Classroom Building Space Original Design Competition, put on by Tsinghua’s property management center.

This year’s contest is still accepting submissions, so for all aspiring wordsmiths, there’s a chance to get your creation in the annals of toilet civilization.