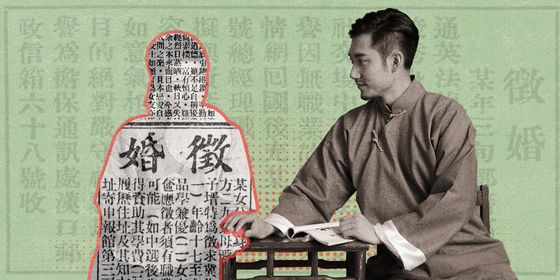

What did ancient Chinese men have to give to get married?

How much does it cost to get married in China? A couple from the Xiaoshan district of Hangzhou discovered the price the hard way last week.

The engaged couple, who had been dating three years, became the focus of public attention when their WeChat conversation was published on Weibo. In the chat, the man said that it was too much of a burden for his parents to buy an entire new apartment before their marriage, so he suggested his parents provide the down payment for a mortgage. The woman argued that all her friends had gotten fully paid-off apartments as engagement gifts, that her father had agreed to buy the groom a car worth 500,000 RMB, and was he asking her to live in debt?

Predictably, this post triggered discussion with commenters on both sides. In recent years, China has seen skyrocketing costs in “bride prices” and dowries—gifts exchanged by men and women’s families (respectively) to formalize match and give the young couple a start in their new life. This has even extended into extravagant proposals just to pop the question. Currently, a typical gift from the groom’s family is an apartment or cash payment (or both), leading to disagreement as to whether these elaborate expectations put unfair pressure on the groom’s families in today’s property market.

Yet were things really better in the past? There may have been no real-estate bubble back then, but ancient engagements faced no shortage of strange rules and rituals. According to Chinese historical records, in prehistoric times, it was the custom for a man to offer a wild goose as a betrothal gift, because these migratory birds travel at the same time each year, thus symbolizing that the couple would be faithful to each other.

Even in those times, it wasn’t long before the rich decided to up the game, with items such as a deer or deerskin. Cui Yin, a litterateur in the Western Han dynasty, wrote in his article “The Rites of Marriage (《婚礼文》)” that “To prepare the betrothal present, deerskin is the choice (委禽奠雁,配以鹿皮).” And a poem from the Classic of Poetry, the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, goes, “A deer dies in the field, and is wrapped with grass. A girl is thinking of love, and a young man uses it as a gift to propose with (野有死麋,白茅包之。有女怀春,吉士诱之).”

In the Zhou dynasty, according to the book The Rites of Zhou, there began to be six steps to preparing a wedding. First, a proposal of marriage (纳彩). Then, the girl’s name is asked (问名) and a fortune-teller finds out if the couple is well-matched (纳吉). Sending the betrothal gift (纳征) is the fourth step. Afterwards, the two families can set the wedding date (请期) and hold the ceremony (亲迎). At this time, cloth and silk were described as betrothal gifts. Another poem from The Classic of Poetry states: “The honest boy comes to me with cloth, saying it’s to trade for my silks. But the real reason he is here is not to get silks, but to talk with me about our wedding. (氓之蚩蚩, 抱布贸丝。匪来贸丝,来即我谋。)”

In the Warring States period, money began to be used as betrothal presents. But textiles remained the main gift, albeit with some special requirements. According to The Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial (《仪礼》), for the scholar-bureaucrat class, their textiles had to be in certain colors: one is called xuan (玄), black with red tints, which represents the sky; the other is called xun (纁), a yellow-red color symbolizing earth. These two were together considered the most honorable colors in ancient China.

Wedding attire in 2015’s Legend of Mi Yue, featuring xuan and xun (ifeng)

When it comes to the Han dynasty, the gifts varied even more, coming to include not only wild geese and textiles but also included sheep, polished rice, and white wine—30 different gift options altogether.

In the Tang dynasty, the list got whittled down to nine items, but the Zhou’s six-step program was still around, and so were the birds—actually, they saw a renaissance. After the man’s family completed the first step, proposal, accompanied by water fowl, they were required to take a wild goose along every time any representative from their family visited the woman’s family until the actual marriage takes place. And if nobody in the family is a good shot? Well, a video from Sohu claimed that Tang customs allowed chicken or domestic geese as substitutes.

Big birds finally fell out of fashion in the Song dynasty, when tea became the mainstream gift. According to Tianzhongji (《天中记》), a book finished in the Ming dynasty, this was because tea plants react badly to being transplanted, which symbolized the wife’s loyalty to her husband. Even the practice of giving betrothal presents became known as “下茶 (sending the tea),” and if the woman’s family accepts the gift, it’s known as “受茶 (accepting the tea).” The traditon of sending tea as betrothal gift had been passed down to the later Ming and Qing dynasties.

There has been no update so far on the Xiaoshan couple’s situation. Are Chinese men doomed to cough up their (families’) life savings or forever be in a wild-goose chase for a mate? Netizens are still debating, and likely will be for many marriages to come.