Hukou laws, social trust, and the merits of a PKU doctorate under debate in latest controversy

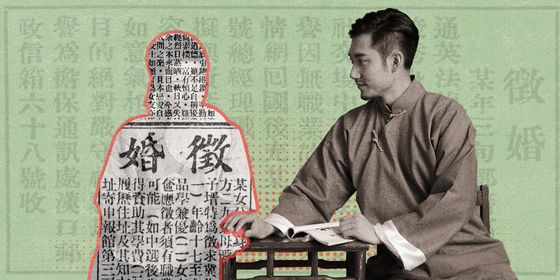

The Chinese phenomenon of “fake divorce” is back in the news once again. One of the top-trending stories of the weekend, attracting nearly 30 million views on Weibo, was a particularly shameful case—reminiscent of Feng Xiaogang’s 2016 flick I Am Not Madame Bovary—involving a Baotou-based “model worker,” academic, and Peking University graduate called Fang and his former wife, known only as Zhan.

The pair married on May 19, 2013 (ironically, the date being a homophone for “I want this to last”) and split in November 2016, ostensibly to secure a Beijing hukou for their new-born son. According to Fang’s plan, this supposedly “fake divorce”—a common strategy to evade regulations regarding residency status and property ownership—would then be annulled when the couple duly remarried, while their son would inherit Fang’s Beijing hukou and gain access to the capital’s supposedly superior education, social, and health services.

Instead, though, Zhan was left without a fen to her name, after Fang reportedly married a woman who was pregnant with his second child and retained their apartment in his name, for good measure (Zhan, meanwhile, was left with their son, and plans to sue for custody and compensation). The backlash triggered by Zhan’s story has since driven Fang out of his job. Divorce lawyers have often warned that, legally, there is no such thing as a fake divorce and no means to compel anyone to (re)marry against their will—and those who think they are safe from a scenario such as Zhan’s might be in for a nasty surprise.

The Zhan-Fang case had particular resonance for netizens because “people tend to have high expectations of PKU students,” as one divorce lawyer told Sixth Tone: As Fang was a senior academic, who had been honored by the Baotou government, the backlash against this high-status “semi-official” was partly driven by public disappointment in the hypocritical behavior of government staff in China. “There are too many men like this around nowadays,” raged one Weibo user. “They’re smart and cunning, and able to profit from society thanks to their self-serving personalities.”

Generally speaking, though, many netizens see get-rich schemes such as fake divorces as a necessary corollary to the byzantine bureaucracy that local governments throw in the way of middle-class couples who are, in many people’s view, just trying to get ahead. On the Netease news platform, the top story last week was about a bizarre “wife swap” between two Shandong couples trying to dodge real-estate taxes. Each couple divorced, and the woman from the first pair married the man from the second, so that the first couple was able to buy an apartment from the second without paying sales tax of up to 20 percent of the asking price—a staggering 12 million RMB (nearly 2 million USD) for a 400 square-meter apartment in the second-tier city of Jinan.

In this case, both couples honored their marital agreements, but the case ended up in court due to a snafu over the paperwork, and the two couples fell out over the final payment of 6 million RMB. The legal resolution, however, also backfired when the court canceled the property transfer, and fined them each for tax evasion.

But instead of piling on the wealthy foursome, many wondered how the court could justify the 50,000 RMB penalty for what was, in effect, a perfectly legal if convoluted plan to dodge the government’s complex tax laws. “This isn’t tax evasion, it’s tax avoidance” was many people’s point of view—even if state media reported the story in a harrumphing manner at the apparent disregard for the sanctity of marriage.

Legally, neither the Shandong couples nor the Beijing pair did anything wrong—but when it comes to adjudicating public morality and mores on social media, Chinese public opinion is a court unto its own.