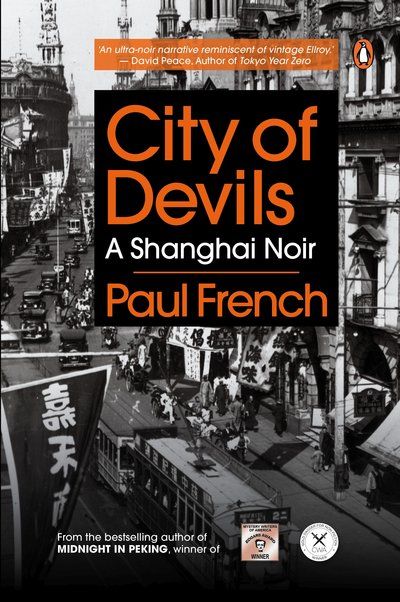

Paul French’s latest book reconstructs Jazz Age Shanghai in sin and splendor

Shanghai between the two world wars was a city of many names and reputations—both the Paris of the East and the Whore of the Orient. It was also a city of a refuge, and “a home,” writes Paul French in his latest book, City of Devils: A Shanghai Noir, “to those with nowhere to go and no one else to take them in.”

Among the “flotsam and jetsam” were European Jews fleeing Fascism, Russians escaping Bolshevism, Chinese peasants looking to get away from the grinding poverty and chaos of the Chinese countryside, and, later, the surge of the Japanese Imperial Army. There were also adventurers seeking their fortune and escaped convicts looking to evade the long arm of the state.

Shanghai was not a colony; it was a concession. In the waning days of the imperial era, it had been, at best, a lopsided and frequently improvised collaboration between the Qing state and various foreign powers. With the final demise of the Qing Empire in 1912, China entered a period of prolonged instability, including periods where the term “failed state” would easily apply. Despite the turmoil and war of early 20th-century China, Shanghai—neither a formal outpost of colonial power, nor locally governed municipality—became both a zone of stability and a refuge for the stateless.

It was also a city of opportunity and reinvention.

French introduces us to this wild world through two Runyonesque figures, born to be characters on a quirky binge-worthy BBC series. (French’s earlier non-fiction work, Midnight in Peking, is being developed for television by HBO)

Jack Riley was an escaped convict, born in the American West, who used a combination of luck and grit to move up the ranks of the underworld from bar owner and bouncer to the slot king of Shanghai. Joe Farren, born Josef Pollak in a Viennese ghetto, arrives in Shanghai to become the city’s great showman and entertainment impresario.

The Shanghai of these characters is a world of equally colorful characters including gun runners and grifters, con men, gamblers, rumormongers, madams, and drunks.

To reconstruct this world, French relies on Shanghai Municipal Archives, consulate records, documents from the US Court for China in Shanghai, contemporary newspapers, and personal interviews. This is first and foremost a story of the subaltern. The less romantic term for “criminal milieu” is “urban underclass,” and accessing such accounts through official archives can sometimes be tricky. No doubt, interpretations were made when it come to speculating about the motivations and even actions of certain characters—a similar narrative strategy French deployed to great effect in Midnight in Peking— but these decisions work for the story, and rarely seem an implausible reading of the source material.

Those readers unfamiliar with Republican-era Shanghai will benefit from the series of maps, lists of street and place names, and a glossary of key terms and slang the author has thoughtfully included. Part of the charm of this world is the polyphony of languages and accents— not just Chinese and English, but Russian, French, Japanese, Tagalog, German, and a host of others. This multicultural patois—and French’s narrative style—are reminiscent of hard-boiled detective fiction of an earlier era.

This is also a book about endings. The opening chapter, set against the backdrop of the Japanese consolidating their control around Shanghai, immediately alerts the reader that little good awaits these characters. Invasion and war, the horrors being perpetrated outside the city and concessions limits—and increasingly inside them—are a sobering backdrop for the garishness of Jazz Age Shanghai, reminding the reader that there are higher stakes here than the usual gangster tale (something Hollywood, or the local equivalent, is sure to appreciate too).

The Devil’s Advocates is a story from our issue, “Vital Signs.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.