A history of cash and payment in the PRC

One-third of shoppers over the age of 60 have been rejected at least once when trying to make purchases with cash, claims a 2018 online survey of Chinese consumers. In January, a Guangdong woman in her 80s burst into tears in a China Telecom office and declared that “seniors…were being kicked out [of society],” after finding out that she could only pay her electricity bill online.

Today’s “cashless society” is a curious reversal from just 30 years ago when almost every financial transaction involved fistfuls of cash and coins in China, which had no credit system or even bank cards. In Xinhua News Agency’s China Album anthology, a man from Hebei named Cao Xianzhong recalled taking along 7,000 RMB’s worth of notes during a business trip in the early 1990s, which he hid in his underpants. “Every time I needed to use money, I had to find a washroom,” Cao reminisced.

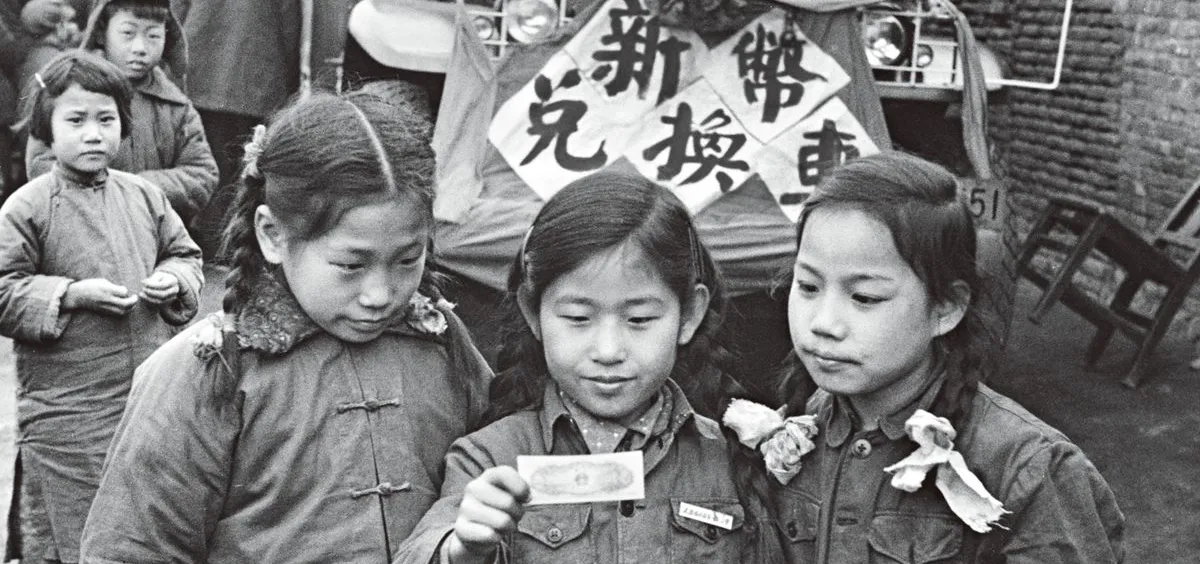

Beijing residents exchange first series renminbi notes for the second series in 1955

China has a long history of using paper currency. The jiaozi (交子), a type of promissory note issued in Chengdu in 1032, is regarded as the earliest form of paper money in the world. However, the country’s modern currency, the renminbi, has a history of only 71 years. It was first issued by the People’s Bank of China in 1948, shortly before the founding of the PRC.

Available as banknotes only, the first series of renminbi had 12 denominations, from 1 to 50,000 yuan, and a total of 62 designs. After the government brought an end to hyperinflation, these notes were replaced by the second series of renminbi in 1955, re-evaluated to a rate of 1 new yuan to 10,000 old yuan (a change that many found difficult to accept).

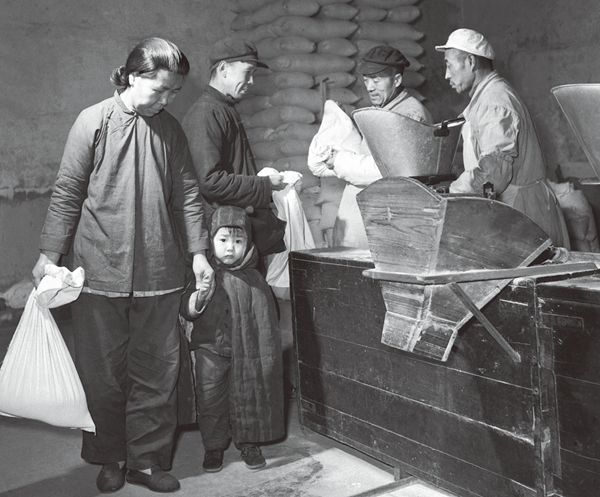

Cash alone, though, was not enough to purchase goods in the planned economy. Under China’s grain rationing system, introduced in 1955 in response to food shortages, purchasers had to present coupons that showed how much of an item they were allowed to buy—whether food, fuel, or consumer goods like bicycles and televisions.

A Tianjin woman buying rice with coupons in 1958

Coupons were allocated to each household based on its productivity. The number and ages of family members, and the physical demands of the labor they performed, all factored into the calculation. Many households also bartered with their coupons for surplus items from their neighbors, though this was illegal.

According to the Dahe Daily, in the summer of 1993, a mother in Henan province died and left behind her lifelong savings in grain coupons, worth over 600 kilograms, believing that this could guarantee that her children wouldn’t starve. Unfortunately, the ration system had been gradually phased out during the market reforms of the 1980s as China’s food and commodity supply caught up with demand, and even created surpluses. Coupons officially stopped circulating in January 1993.

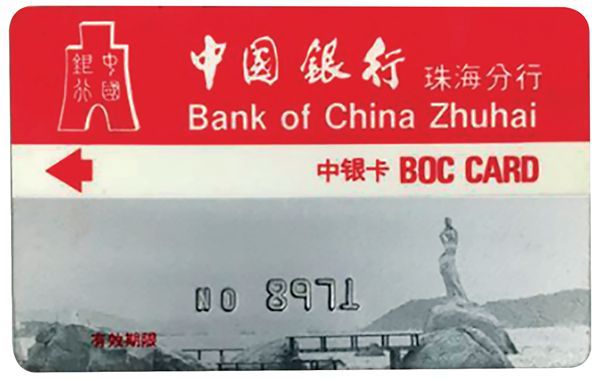

China’s first credit card

In 1985, Bank of China employee Zhou Bingzhi went to visit relatives in Hong Kong, and saw people using credit cards for the first time. Amazed by the convenience, Zhou shared this discovery with the bank branch in Zhuhai, Guangdong, where he worked. China’s first credit card was born two months later. Known as the “Bank of China” card, it had no magnetic stripe and no chip, and only worked in Zhuhai; every time it was swiped, the user had to call the bank to authorize the transaction.

Renminbi banknotes saw three more redesigns in 1963, 1987, and 1999. The second series is the most sought-after by collectors, as it contained a unique 3 RMB denomination. Since some denominations were printed in the Soviet Union, the second series was recalled by the government in 1964 at the nadir of Sino-Soviet relations—thus making any surviving notes worth tens of thousands of yuan today.

Two tourists to Hangzhou experience cashless payment in 2017

Online and mobile payment began developing in the late 1990s. In 2004, the Alibaba Group established Alipay, which overtook PayPal as the world’s largest mobile payment platform in 2013, the same year that Tencent launched WeChat Pay. The People’s Bank of China states that China saw 60.5 billion mobile payment transactions in 2018, compared to 1.7 billion in 2013, suggesting that cashless payment is an irreversible trend.

Alipay is now accepted at many stores abroad

However, China’s central bank also stepped in to defend the sanctity of the historic paper currency that year, after a 67-year-old man went on a tirade in a Heilongjiang supermarket that refused his notes: “Renminbi is China’s national currency. It is illegal to refuse cash.”

Cash Back is a story from our issue, “The Good Life.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.