The history of indoor heating in the PRC

“Northerners rely on their radiators to survive winter, while southerners rely on integrity!” Every year around November 15, the date when central heating systems around China are typically fired up, this self-mocking mantra is chanted by millions of southern residents that continue to be left out in the cold.

In the 1950s, when China began to install central residential heating with assistance from the Soviet Union, serious energy shortages meant that it did not have capacity to heat the entire country. Premier Zhou Enlai suggested that the colder area north of the Qinling Mountains and Huaihe River, or about 34 degrees above the equator, should be prioritized under the new heating policy.

Over 60 years later, this policy persists, often creating arbitrary divides between heating haves and have-nots. The city of Xinyang, Henan province, which straddles the Huaihe, is frozen out of the heating policy because more than 75 percent of its population lives south of the river. Yet just 66 miles north in Zhumadian, where the climate is not discernibly different, citizens can stay cozy indoors all winter long.

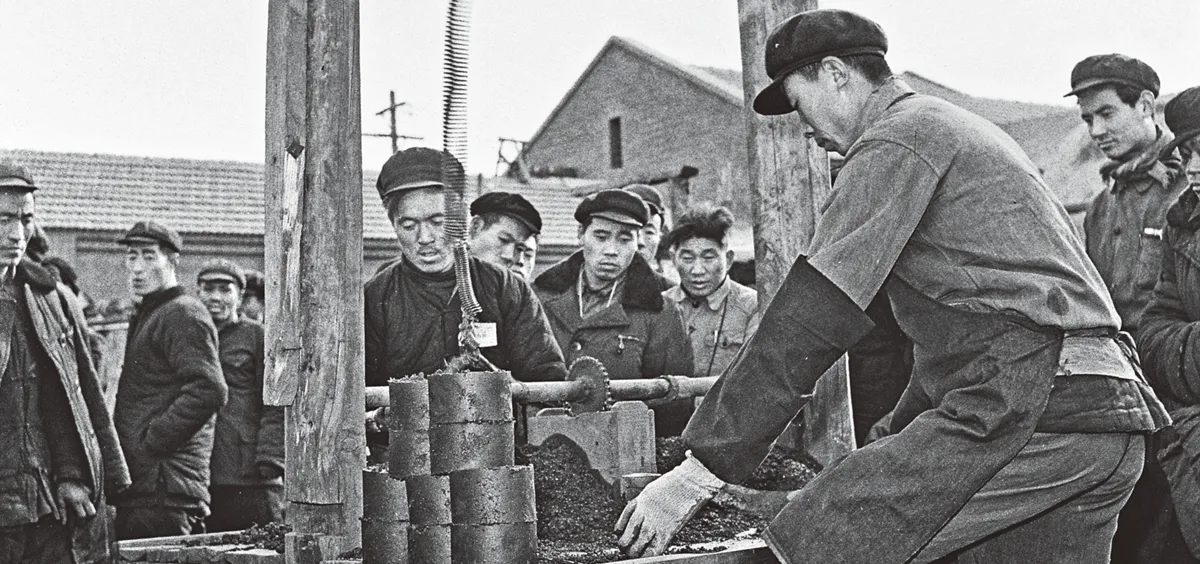

Members of a people’s commune build a new kang in Ninghe county, Hebei province, in 1958

Such inequities trigger fierce policy debates almost every year. In 2012, Zhang Xiaomei, member of China’s top advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, proposed during CPPCC’s annual meeting to push the heating line southward, since the gloomy, humid winters of the south can be even more miserable than the “dry cold” common in the north.

It would be a mammoth undertaking, though, to install central heating in all of southern China’s residential neighborhoods that have been designed without this system in mind. The realities of carbon emission also make the heating policy unlikely to change, at least until the country finds alternative energy sources. Jiang Yi, a professor from the Building Energy Conservation Research Center at Tsinghua University, told the Beijing News in 2015 that if China provides central heating to all the residential urban areas in the south, it would need to burn an additional 50 million tons of coal each year.

Before there was central heating, northerners traditionally slept on the kang (炕), a heated brick bed that burned wood and coal underneath. Archeological findings show that the kang already existed by the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). In later centuries, the device was improved and popularized by the northeastern Manchu people, and continues to be widespread in northeastern villages today.

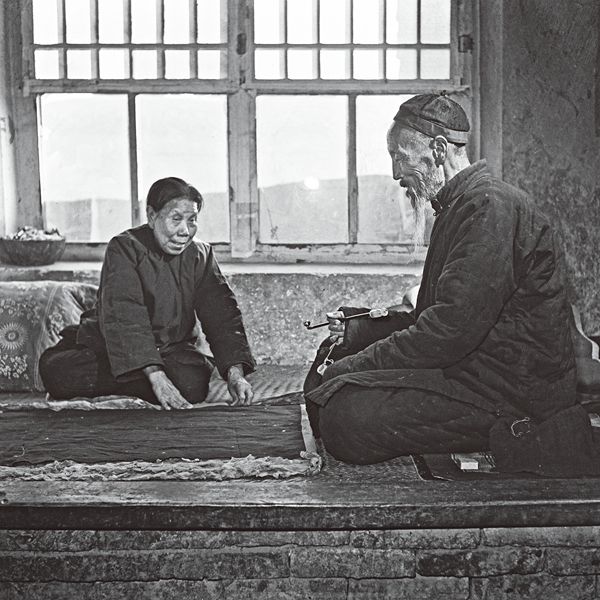

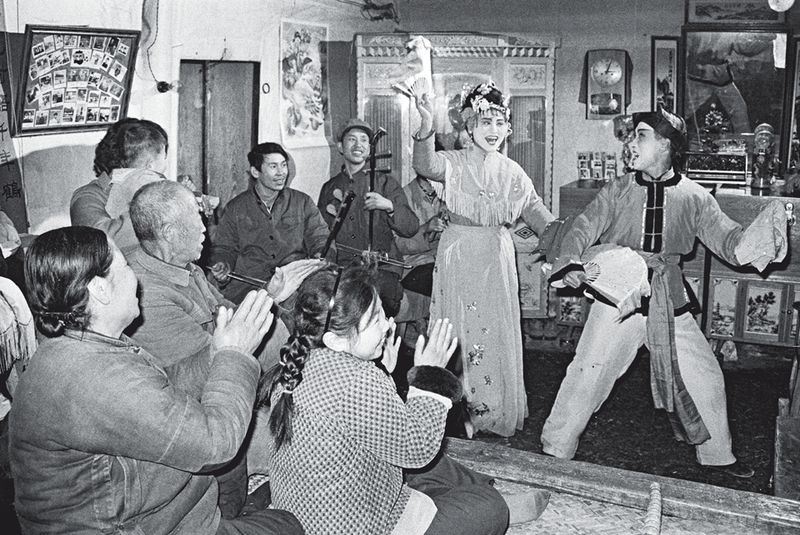

Socializing on the kang may have inspired the errenzhuan folk duet in the northeast

A northern folk saying goes, “a kang makes up half of a house (一间屋子半间炕).” The kang is usually the biggest heated structure in a northern dwelling—it may just be a heated part of the floor, as in the traditional homes of Chaoxianzu, China’s Korean minority—and serves as a bed, dining area, and living room in one. At mealtimes, a low table is placed on the brick bed, giving the family a toasty place to gather around and eat. When guests enter the house, the host typically greets them by saying, “Come sit on the kang and get warm!”

“On the kang, neighbors talk with each other amusingly, smoke, and sing,” according to the Xinhua Agency’s China Album, which goes on to call kang-based banter the “prototype of errenzhuan” (二人转), a genre of song-and-dance folk duet popular in the northeast.

Southerners, rather than the kang, historically preferred to heat rooms with braziers, which resemble a cooking wok filled with coal heated in the kitchen fire. In Ningxiang, Hunan province, a brazier is quite literally a housewarming gift traditionally given to families when they move.

Central heating kicks in north of the Qin-Huai Line in mid-November every year

Neither the kang nor the brazier can exist without coal. China has been burning coal for over 3,000 years, and it became a widespread source of fuel after the Han dynasty. Prior to 1949, coal usually came in the shape of round balls, which were hard to heat—it might take about half a kilogram of firewood to ignite them, and they usually burned out before they were all used up, creating waste.

To improve coal’s combustion efficiency, a Beijing coal dealer named Guo Dewen came up with a new design in 1949: He compacted the coal into small cylinders and drilled holes in the middle, which allow the coal to “breathe” while it burns. The new form of coal, called the “honeycomb briquette (蜂窝煤),” saved an estimated 30,000 tons of coal for Beijing every year.

Guo cleverly advertised his product in cinemas, and newspapers soon wrote editorials to promote his invention. “Whenever I mentioned my father, people knew his name, saying, ‘That’s the guy promoting honeycomb coal in the cinema,’” Guo Chunfu, Guo Dewen’s son, recalled to China Album.

Temperatures are usually no lower than 18 degrees Celsius in homes with central heating

As with other commodities under the planned economy (1953 – 1992), Chinese citizens needed ration tickets to buy coal. Each month, coal dealers pulled carts stacked with cylindrical briquettes through the neighborhood, which they would distribute to each household according to their allowance by the state. “One coalman was in charge of one or two hutongs. We drew a cart with a ton of coal every time, six times a day,” former Beijing dealer Wen Danqing told China Album. “Sometimes we had to carry the coal upstairs. It was really difficult to climb to the fourth or fifth floor.”

In 2016, three years after Guo Dewen’s death, the honeycomb briquette was nominated for awards at Beijing Design Week, along with projects like the Beidou Navigation Satellite System and Nanjing’s Yangtze River Bridge. “I was very surprised to hear this news,” Guo Chunfu said. “It proves that people recognize the contribution of the honeycomb briquette to the country and the people.”

Since the end of 2016, though, China has been turning to natural gas and electricity for winter heating to improve its air quality, with some northern cities making residents quit “cold turkey” by confiscating coal-burning stoves. By 2018, 50 percent of winter heating was produced by clean energy in the north, and the figure is expected to rise to 70 percent by 2021, saving the nation 150 million tons of coal. As with fires under beds and energy-efficient briquettes, China is once again looking for an innovative way to turn up the heat.

Hearth Warming is a story from our issue, “Grape Expectations.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.