Stefen Chow and Huiyi Lin measure the poverty line in photos

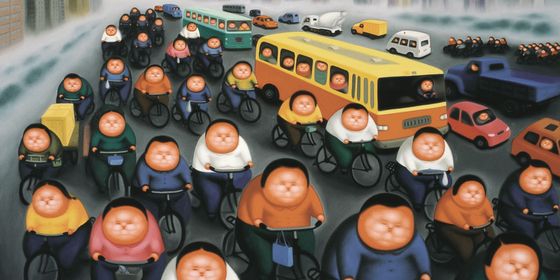

In 2010, photographer Stefen Chow and economist Huiyi Lin, originally from Singapore, were living in Beijing and witnessing society undergoing one of the biggest economic transformations of the last century.

The fast pace of change in their adopted home inspired the couple to turn back to basics—food. They came up with the idea of purchasing items at the market for 3.28 RMB (0.48 USD), a daily budget equal to what someone living on the national poverty line that year could spend. Arranging the meats, produce, and steamed buns they brought home on the day’s newspapers, the husband-wife team snapped photos which they uploaded to their website.

A decade later, their award-winning project The Poverty Line has documented food choices that can be purchased at the poverty line in 35 countries, and the couple’s photographs have been exhibited worldwide. As they prepare to publish a book titled after their project in 2021, Chow and Lin sat down with TWOC at their Beijing studio to discuss their inspiration.

“Lagos, Nigeria,” October 2015

How did the project start?

Lin: Due to our experiences living in Beijing and traveling the world, we were constantly discussing issues associated with poverty, social development, and the happenings of our local community. I am a facts-and-figures person, viewing everything from a public policy and economic lens, whereas [Chow] likes to talk to locals and focuses on big-picture ideas.

Things were happening so quickly in China in the 2010s; so we decided to document it. We came up with the idea of photographing the food which could be purchased at the poverty line to show that even though things were moving fast for the people at the top in China, it didn’t mean that it was moving fast for the people at the bottom.

Chow: In 2011, our works focused on China’s poverty line were published by NPR. In the United States, most of the comments centered on how people were able to survive on so little food. But then it went viral in Europe—our website even crashed because of an influx of visitors from Russia. Many of these people commented on how fresh the foods looked and how good the vegetables must taste in comparison to what they could get in their home countries for that price. These comments really opened our eyes to the topic of food security and prompted us to expand it into a multi-country project.

How do you add a new country to the list?

Chow: So far, we have documented The Poverty Line in 35 different countries and territories around the world. We just finished up four countries in Africa.

Lin: Before we start, I do the research to make sure that all the numbers are accurate. To me, it is very important that everything is correct. My husband focuses on the way it looks, so we complement each other well.

Chow: Once we get on location, we will end up buying anywhere between 6 to 200 different items for that country. We now have a formula to it; but it didn’t start out that way. Sometimes, it just takes a couple of days, but it can take up to a week. In developed countries, it is simpler because the prices are clearly listed in the supermarket. But for some countries where the prices aren’t fixed, we pay trusted people to go into the markets and buy as much as they can on our poverty line budget. There is a lot of production work on the ground.

“Sydney, Australia,” August 2011

What is it like collaborating with your spouse?

Chow: We met as undergrads at the National University of Singapore and we were quite opposite from the start. Lin became a public servant for the Singapore government, whereas I joined a team and trained for three years to climb Mount Everest, which I did in 2005. Afterward, I became a commercial photographer.

Lin: For us, coming to Beijing together was an opportunity to take a risk and explore. We were originally only going to stay for two years, as I did my MBA at the Tsinghua-MIT Sloan program. Coming to China was also a way for us to understand our Chinese roots and see the world from a new perspective. Because of my background in public policy, I often think about social issues from a top-down approach and Stefen forces me to think about things differently.

Chow: It has definitely been an interesting and positive experience to work on this as a couple. We have been married for 12 years and now have two children. Our career paths are completely different and, in general, our viewpoints are also different. For The Poverty Line, we debated and argued and put our brains together. We still do critique each other a lot, which I think allows for the refinement of ideas.

What have you learned through The Poverty Line?

Lin: I think that sometimes the more you focus on the numbers—and the more you know about a subject in general—the more difficult it can become to get to the heart of the matter. Working with vast amounts of data can sometimes become immobilizing. The Poverty Line has forced me to simplify the message.

It has also forced me to reflect on what can catalyze change. I realize that art is definitely a platform for change. Through our exhibitions at places like the United Nations, I have met experts in the field who know the subject backward and forward, but when they see the poverty line presented in this way, it becomes something new and it sparks new ideas and thoughts.

Chow: Focusing on these cross-border food security issues has expanded my worldview. One of my underlying thoughts through this whole project is that the human species is complicated. Where there are humans, there are problems. It doesn’t matter if you are rich or poor; in a developed country or in a developing country. But when you have problems, you also have solutions.

“Delhi, India,” December 2011

Why do you think the project has become so poignant?

Chow: Focusing on poverty through a series of food choices is poignant because eating is something that is universal. If you are alive—whether you are poor or rich—you have to eat. Everyone has a relationship with food and The Poverty Line taps into that.

The project is self-funded, not grant-based. We’ve been doing it because we felt like it was important to us. I think that it is going to end up becoming a work that will last a lifetime, because the poverty line and economic circumstances are always changing. For us, art has become a platform to work together and communicate about the issues that we are concerned will negatively affect the future world of our children. The two of us have a synergy and art has become the way to combine both of our voices.

“Seoul, South Korea,” October 2012

“New York, USA,” October 2011

Drawing the Line is a story from our issue, “Contagion.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.