The ongoing fight against discrimination for Hepatitis B patients in China

“Please do not discriminate against those with Hepatitis B,” pleads a comment on Weibo under a video about the disease by state-broadcaster CCTV. “It has been four years since I was diagnosed. My dream of joining the army has been elusive. I have been living in the darkness. Years of examination, days of medication; I’m even afraid to date.”

An estimated 70 million people in China suffer from HBV, a vaccine-preventable liver infection caused by the Hepatitis B virus. A sexually transmitted disease, the Hepatitis B virus is spread through body fluids. According to the World Health Organization, symptoms are generally mild and can come and go.

Some people, however, may become seriously ill with jaundice, and suffer liver failure and cancer. In China, HBV-induced cirrhosis contributes to 95 percent of liver cancer cases every year, and deaths from HBV-induced liver cancer in China account for over half of global mortality from such cases.

Ironically, mass vaccination campaigns for tuberculosis and other infectious diseases in the late 1970s were to blame for large-scale transmission of the Hepatitis B virus. From 1970 to 1992, when needle-sharing for vaccinations was common, the number of HBV patients increased by 80 million to a total of 120 million. Between 1970 and 1990, the Chinese population grew by more than 313 million births, with 30 million born with the virus, likely from mother-baby transmission during childbirth.

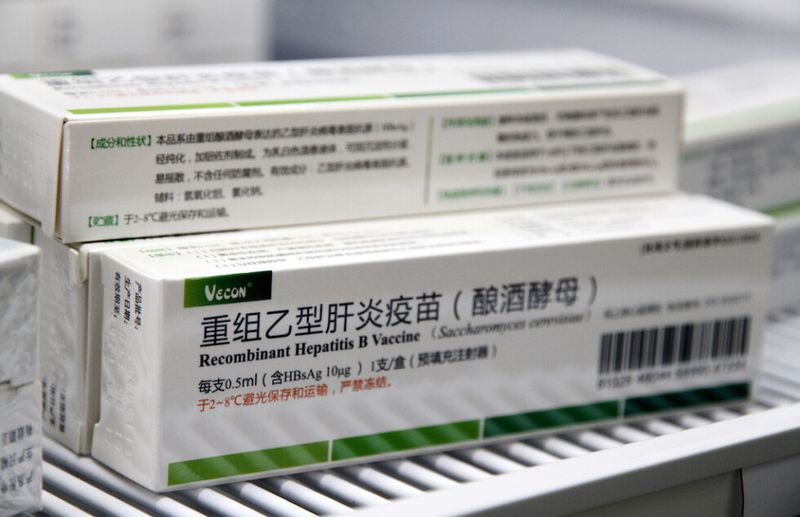

In 1992, Merck & Co., a US pharmaceutical giant, agreed to transfer its technology and expertise to China and began producing a HBV vaccine in the country at no profit. But patients had to pay for the vaccine themselves, and it was prohibitively expensive, which contributed to a vaccination rate of just 30 percent prior to 2002—far below what is required to achieve herd immunity.

Parents used to have to pay to get their children vaccinated against HBV (VCG)

The vaccine was incorporated into China’s free routine vaccination program in 2002. Between 1992 and 2014, vaccinations helped reduce the prevalence of HBV infection by an estimated 80 million among children under 15 who would have suffered from the virus without the vaccine. Vaccination also effectively blocked 90 percent of transmission of HBV between mothers and infants.

Despite increased vaccination, there is still a large number of HBV patients in China who were infected before the vaccine became available. According to a CCTV broadcast on July 28, World Hepatitis Day, about 90 percent of China’s 70 million HBV sufferers have yet to receive treatment, largely due to low awareness about the disease; some may not even know they have the infection.

Lack of knowledge about the disease also contributes to discrimination against patients, whether in study, work, or social contact. In 2015, Wu Xinyi, a college junior, committed suicide after her university forced her to live in isolation for 34 days when they discovered she was an HBV carrier—Wu and her school only discovered her infection after she had tried to donate blood. In 2018, a 61-year-old woman was rejected by multiple nursing homes due to her infection.

Stigma of the disease extends into the workplace in China, where pre-employment physical examinations are common. A 2010 document released jointly by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, Ministry of Education, and Ministry of Health stipulated that medical institutions must not include an HBV test in pre-employment examinations.

However, in 2016, an HBV patient known under the pseudonym Xiao Lin was rejected for a job by a Hangzhou mechancial technology company after his infection was discovered in his physical examination. He had not been informed that he would be tested for HBV. Xiao Lin was awarded 12,000 RMB in damages after he took the case to court.

This discrimination has even helped create a market for phsyical examination “substitutes,” who will take the place of HBV carriers during medical exams to ensure their infection is not discovered. Fees for these replacements can be tens of thousands of yuan.

Lin Fei (pseudonym), an HBV carrier, told NetEase that she sought help from a medical exam subsitute agency to ensure that she could pass the physical exam to take up a post as a primary school teacher. The agent quoted Lin a fee of 1,500 RMB for each test taken by substitute; the whole procedure would cost 8,000 RMB.

Raising public awareness of the disease is vital to avoid such unnecessary workarounds, as many in China still wrongly believe that the virus can be transmitted through casual contact, such as eating together. Activists and HBV patients have launched nationwide campaigns since 2010 to rectify these misunderstandings.

In 2012, Lei Chuang, an HBV patient, stood outside a shopping mall in Beijing with a sign that read: “I am a HBV carrier. I want to tell you that the virus cannot be transmitted from routine contact or by eating together, but there are many people who are afraid to have lunch with us. So let’s go out for lunch—my treat.”

Treatment for the disease has also been made easier in China, and is available via the National Health Insurance Scheme. In January this year, Vemlidy, an important medication for HBV treatment, was brought under the scheme. Its price was reduced from 1,180 RMB per box to 880 RMB, partially covered by insurance. Together, these measures reduce the financial burden on the typical HBV patient by 80 percent.

Zhang Wenhong, a Shanghai-based infectious disease expert who has become famous as one of the key public faces of China’s Covid-19 response, has helped raise awareness of HBV further when he spoke about the disease earlier this year for CC Forum, a TED Talk-like series of public education videos: “HBV can be easily treated…in 10 years, some patients can be clinically cured and stop taking medication. The only thing that they need to do is to have regular visits to doctor, perhaps every six months.”

“There is no difference in the quality of life of the infected group versus the non-infected,” said Dr. Zhang. “Get married, have babies, stay up late, or play computer games. Anything is OK.”

One Weibo comment underneath Zhang’s speech summed up the changes that are being made: “Before, you couldn’t work and couldn’t get married. If you walked on the street in a place where people knew you, you even had to hide your face. I’m so grateful that medicine has developed.”

Cover image from VCG