Five audacious tomb robberies from ancient history to today

“There are no unopened tombs, just like there are no immortal people,” wrote the Jin dynasty (265 – 420) scholar Huangfu Mi (皇甫谧), whose essay “Criticism of Death” lamented the futility of nobles staging elaborate burials only to profit robbers and thieves.

The custom of peizang (陪葬, “accompanied burial”), or burying meaningful objects with the dead, has existed in China since prehistoric times. In tombs dating back to the Neolithic era, archeologists have discovered valuable and practical items such as jade, pottery, bronze, and textiles meant furnish the “earth palaces (地宫)” of the powerful people in the afterlife. Some early funerals even practiced xunzang (殉葬, “sacrificial burial”) by burying horses, servants, and concubines with the deceased, though they were gradually replaced by models and figurines like the Qin Emperor’s famous terracotta warriors.

These buried treasures are now a boon to archeologists seeking answers to historical mysteries, but in the past, opening a tomb was a quick way for plunderers to get rich, or conquering armies to make a statement. Here are some of the biggest, strangest, and most destructive tomb-robbing attempts from ancient history to today:

Prince Liang’s Tomb Robbery (second to third century)

Prince Liang of Xiao was buried with his lesser-known terracotta army on Mount Mangdang in Henan province (VCG)

Though tomb-robbers have operated for as long as nobles have been burying themselves with treasure, the raid by warlord Cao Cao (曹操) on the tomb of Liu Wu (刘武), a son of Emperor Wen of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) who was posthumously known as Prince Liang of Xiao, may be one of the earliest professional efforts. According to historical records, Cao even appointed a “gold-seeking field officer (摸金校尉)” in his army to search for buried treasure to fund his military campaigns, though probably not to the extent that he could “feed his military for three years” just from one robbery, as claimed in historical accounts written by his (many) rivals. The Records of the Three Kingdoms, the official history of the period, states that “Cao Cao led his army to Mount Mangdang, broke into Prince Liang of Xiao’s tomb, opened the casket, and took innumerable gold and jewels.”

Perhaps due to his tomb-raiding experience, Cao Cao was extra-cautious about his own burial, leaving behind conflicting accounts about his ultimate resting place. A tomb discovered in 2008 in Anyang, Henan province, was finally confirmed to be his in 2018, and it doesn’t appear to have been robbed.

Zhao Mausoleum Robberies (908 – 1914)

One of the plundered “Six Steeds of the Zhao Mausoleum” on display at the Stele Forest Museum of Xi’an (VCG)

The resting place of Li Shimin (李世民), Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), has been plundered multiple times since its completion in 741. Perhaps its most famous robbery was orchestrated by Wen Tao (温韬), a military governor of the Later Liang dynasty (907 – 923) who is best remembered for having plundered 18 out of the 19 imperial Tang tombs in his territory, only excepting the mausoleum of the female emperor Wu Zetian (武则天) due to storms.

According to the New History of the Five Dynasties, Wen Tao openly used his soldiers to help him tunnel into the tombs and make off with the treasures, which he recorded in an inventory. It took thousands of soldiers and carriages a month to transport all that he looted from the Zhao Mausoleum, which held the grave of not only Emperor Taizong, but his empress and 200 other nobles. It’s believed this led to the loss of the only known original copy of the “Preface the Orchid Pavilion Collection,” the foreword to a poetry anthology written by the famed fourth-century calligrapher Wang Xizhi (王羲之). As legend goes, the illiterate Wen did not know the value of the old book in the Emperor’s crypt, so he threw it aside in order to keep the silken box in which it was kept.

The tomb was robbed again in 1914, and the thieves made off with a series of stone reliefs called the “Six Steeds of the Zhao Mausoleum,” two of which wound up in the antiques market overseas. Those are now on display at the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. The other four, which were intercepted by a patriotic antique shop owner surnamed Ma, are in the Stele Forest Museum of Xi’an.

Eastern Qing Mausoleum Robbery (1928)

It’s believed that every tomb in the Eastern Qing Mausoleums has been plundered at some point (VCG)

Like Wen Tao, warlord Sun Dianying (孙殿英) saw the usefulness of an army in raiding tombs. An occasional ally of the Nationalist government of the Republic of China, Sun was ostensibly defending the Nationalists’ northern borders in June 1928 when he garrisoned his private troops near the Eastern Mausoleum of Qing dynasty emperors in Jixian county, now part of Tianjin. There, under the pretext of doing military exercises, he all but emptied the tombs of the Empress Dowager Cixi and the Qianlong Emperor.

Sun’s methods were crude to the extreme: His soldiers blew open the entrance to the tombs with dynamite, and threw the imperial corpses into the dirt in order to steal the treasures they were buried with. They also desecrated the Empress Dowager’s mummified body, pried open her jaw to extract a pearl from her mouth, and left the body out in the sun for over 50 days, causing untold damage. In the Qianlong Emperor’s tomb, the robbers destroyed valuable paintings and calligraphic works while scrambling for precious stones and metals.

In all, it reportedly took 30 trucks to carry away all of Sun’s plunder. The public was outraged by his actions, and the last Qing emperor, Puyi (溥仪), demanded punishment for Sun. However, the story goes, Sun gifted Cixi’s pearl to Soong Mei-ling (宋美龄), wife of the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石), and tried to send the Qianlong Emperor’s “Nine Dragon Jeweled Sword” to Chiang himself (though it disappeared en route), and smoothed over his crime.

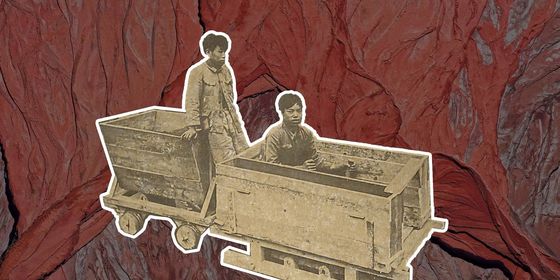

Beiping “Feng Shui” Robberies (1935 – 1936)

Tomb-robbing was common in the relatively lawless days of Beijing in the 1930s and 40s (VCG)

In 1936, reports of strange characters coming and going from a house outside Xuanwu Gate in Beijing (then known as Beiping) led the police to capture a gang that had plundered an unknown number of graves belonging to prominent families in the city. The criminals had help from an unusual quarter: a well-known feng shui “master” named Liu Runzhai.

Liu, who was in his 60s, had already made a name for himself among the Beiping elite, who paid a considerable fee to ask him about potential locations for their family tombs. Unbeknownst to them, Liu discovered he could profit further by selling this information like a proto-data thief. After inquiring minutely into the objects that the deceased would be buried with, Liu reported both the location and contents of the tomb to robbers for another handsome commission. The gang eventually confessed to 11 robberies, and its leaders, including Liu, were put to death.

Hongshan Culture Site Robberies (1980s – 2015)

The C-shaped jade dragon, believed to be a religious object, has become emblematic of the Hongshan Site (VCG)

Known as the “biggest tomb-raiding case since the PRC’s founding,” the robberies at the Niuheliang Hongshan Cultural Relics Site in Liaoning province were led by the notorious Yao Yuzhong, who was nicknamed the “Grandmaster of Tomb-Robbery” for his prolific 30-year career. Yao learned looting techniques from his father, used feng shui and astrology to estimate the likely location of ancient tombs, and made no secret of his trade, even offering Hongshan relics in lieu of cash when he gambled at high-end casinos. He boasted of being the “reincarnation of the original builder” of the Hongshan tombs, and claimed he was performing a public service, as his skills made him “better than 100 archeologists.”

In total, police rounded up a network of 225 criminals spread across seven provinces, including four archeologists, when they finally cracked the case in 2015, and recovered estimated 500 million RMB’s worth of artifacts dating from the Neolithic period, such as a semi-circular jade relic that may be the prototype of a dragon. Yao was given a suspended death sentence for his crimes.

Cover image from VCG