Idioms about royalty from China’s imperial past

After their interview with Oprah Winfrey last week, Prince Harry and his wife Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, have the whole world talking about the dysfunction in the British royal family. But the controversy and ceremony of the House of Windsor are nothing compared to the intrigue in the extended households of imperial China.

Imperial courts were so ripe with mystery, backstabbing, and power politics that they gave birth to a whole TV genre—the gongdouju (宫斗剧), or palace drama. China’s own monarchy fell in the Revolution of 1911, though the last emperor Puyi stuck around the Forbidden City until 1924 and died in 1967. Still, the prestige and intrigue of the palace live on in idioms that still refer to it today.

九五之尊 jiǔ wǔ zhī zūn

The imperial throne

This term literally means “as honorable as the number nine and five.” Though every Chinese can tell you this chengyu refers to the office of the emperor, it’s not widely known why these two numbers were chosen. A simple explanation is that ancient Chinese divided numbers into two different categories according to the yin-yang system: odd numbers are believed to contain yang energy, while even numbers were yin.

Nine, as the largest single yang number, symbolized the highest position, while five was in the middle, meaning neutral and impartial. People took these two numbers to refer to the emperor, who was believed to occupy the highest position under heaven.

His majesty was in the most honorable position under the heaven. Why would he put himself in such a danger?

Huángdì bìxià shì jiǔ wǔ zhī zūn, yòu zěnme huì yǐshēn-fànxiǎn?

皇帝陛下是九五之尊,又怎么会以身犯险?

母仪天下 mǔyí-tiānxià

Be the motherly model of the nation

The empress, as the wife of the emperor, was often addressed as “the mother of a nation (一国之母 yì guó zhī mǔ).” Such a title bestowed not only lofty status, but demanding requirements. An empress was required to be dignified, elegant, generous, loving, and always obedient to the rites. As the noblest woman in the empire, the empress must be a model to all her subjects—especially female subjects. This chengyu summarized what an ideal empress should be like:

The empress should be the motherly model of the nation, so the emperor had to marry a women who is both virtuous and talented.

Huánghòu yīnggāi mǔ yí tiānxià, suǒyǐ huángdì bìxū qǔ yígè décái-jiānbèi de nǚzǐ.

皇后应该母仪天下,所以皇帝必须娶一个德才兼备的女子。

六宫粉黛 liùgōng-fěndài

Beauties in the imperial palace

There could be only one empress to the emperor, but that did not mean the emperor restricted himself to one woman. The imperial household would normally contain numerous concubines too.

This chengyu refers to those imperial concubines and maids. 六宫, literally meaning “six palaces,” refers to the six sleeping chambers of the emperor. The term 粉黛 originally referred to cosmetics, and later was used as shorthand for beautiful women. The chengyu refers to all the beautiful women living in the imperial harem.

In his “Song of Everlasting Regret (《长恨歌》),” poet Bai Juyi (白居易) used the phrase to describe the beauty of Yang Yuhuan (杨玉环), a famous concubine of Emperor Xuanzong during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907):

Turning her head, she smiled so sweet and full of grace; that she outshone in six palaces the fairest face.

Huímóu yí xiào bǎi mèi shēng, liùgōng-fěndài wú yánsè.

回眸一笑百媚生,六宫粉黛无颜色。

金枝玉叶 jīnzhī-yùyè

Gold branches and jade leaves

This phrase used to literally refer to beautiful foliage, but later became a metaphor for imperial descendants, especially the emperor’s daughters and sons. Today, it is sometimes also used to to refer to spoiled children.

Today’s kids are all like gold branches and jade leaves; who among them can handle a tiring job?

Xiànzài de háizimen dōu gēn jīnzhī-yùyè shìde, shéi néng gàn de liǎo zhè zhǒng lèirén de huó?

现在的孩子们都跟金枝玉叶似的,谁能干得了这种累人的活?

A similar phrase is 凤子龙孙 (fèngzǐ-lóngsūn), literally “son of the dragon and grandson of the phoenix.” In traditional Chinese culture, both the dragon and the phoenix are symbols of royalty, so this chengyu also refers to descendants of the royal family or to aristocrats.

Once a descendant of the dragon and phoenix, he is now no different from a beggar.

Tā yuánběn shì ge fèngzǐ-lóngsūn, xiànzài què hé qǐgài méi shénme liǎng yàng.

他原本是个凤子龙孙,现在却和乞丐没什么两样。

皇亲国戚 huángqīn-guóqì

Members or relatives of the royal family

This phrase generally refers to those related to the imperial family, by blood or by marriage. Royal relatives were often very powerful, so this chengyu is now used to refer to someone of influence and power, and is frequently used in an ironic way:

He is the boss’s brother-in-law! Don’t displease a relative of the royal family!

Tā shì lǎobǎn de xiǎojiùzi! Búyào dézuì zhè zhǒng huángqīn-guóqì!

他是老板的小舅子!不要得罪这种皇亲国戚!

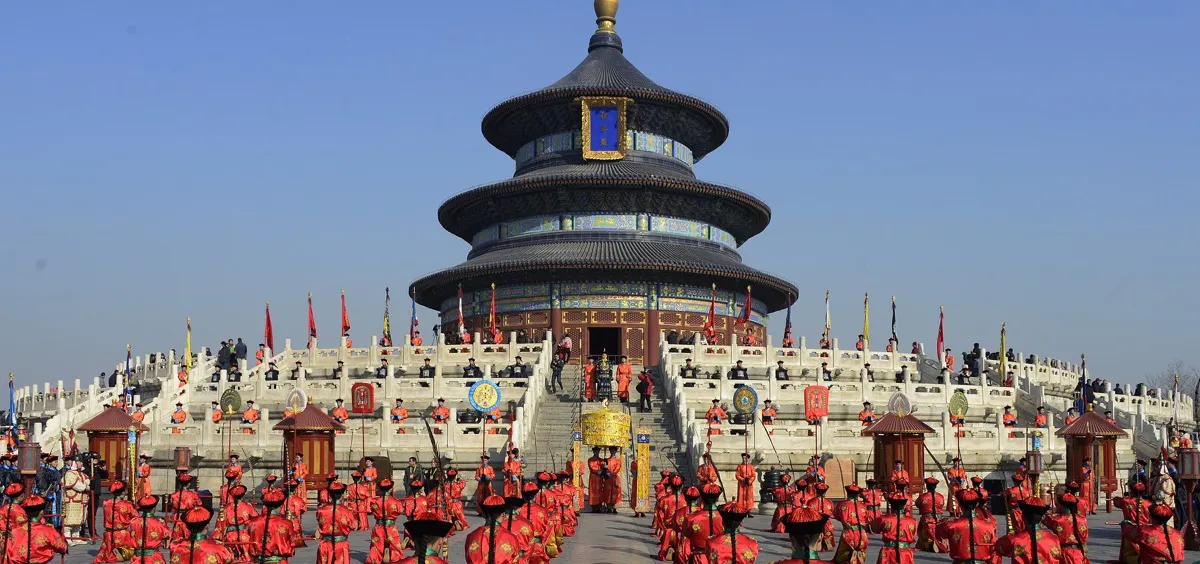

Cover Image from VCG