Why do Chinese fans expect social responsibility and absolute morality from stars?

It was a fall of Icarian scale. For over a decade, actress Zheng Shuang had been a rising star, taking lead roles in popular TV shows, receiving prestigious awards and luxury brand endorsements.

But it all came crashing to the ground on January 18, 2021, when Zheng’s ex-boyfriend Zhang Heng revealed that the couple had become parents to two children in the US by surrogacy a year prior, and that Zheng was refusing to sign papers that would bring the infants back to China.

Zheng hiring two surrogate mothers in the US, while surrogacy is illegal in the PRC, drew the public’s ire as it illustrated how the rich and famous can skirt the country’s laws. But perhaps worse was a purported voice recording of Zheng complaining that the fetuses were too far along to be aborted, and her mother suggesting they “abandon” the children after they are born. The public storm was so large that the State Administration of Radio and Television waded in, issuing a statement on their WeChat account that “surrogacy and abandonment [of children] are against social morality” and, as a result, “we will not provide victims of scandal opportunities and platforms to speak out and show their faces.”

Within two days of the incident, Prada had withdrawn an endorsement contract with Zheng. Her awards were revoked, welfare activities cancelled, and her face replaced in new film releases. The offences have since started to pile up, culminating in April with accusations that Zheng has been evading taxes—echoing the 2018 scandal that dethroned megastar actress Fan Bingbing, who disappeared from the public eye for months after—and making a comeback from the 29-year-old seem impossible.

Like most celebrity cultures across the globe, China’s singers and actors, or mingxing (明星), are no strangers to scandal. But whereas tales of infidelity and drug-addiction rarely lead to Hollywood stars getting cancelled—and may even boost their notoriety—poor private conduct can destroy entire public careers in China.

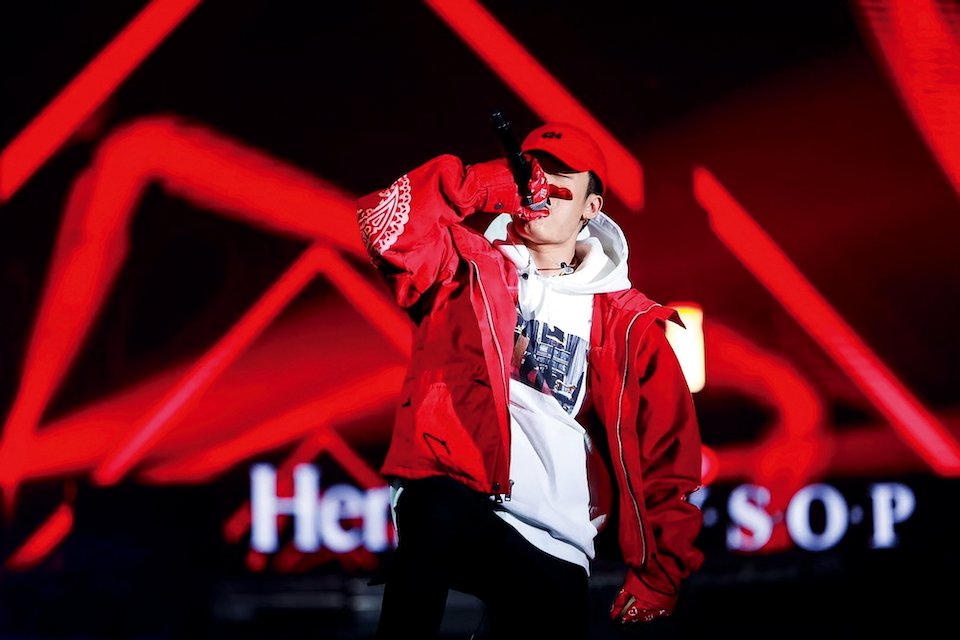

Take actress Li Xiaolu, revealed to be having an extra-marital affair with the rapper PG One in November, 2018. Although both denied the accusations, Li and her husband divorced shortly after, and the career of neither entertainer has recovered: Li has not released a movie since 2019, and PG One has withdrawn almost entirely from public life. A bar in Xi’an gave him a chance for a “comeback” last summer only on the condition that he sang offstage while another rapper lip-synched the words onstage—but he was discovered by the audience within ten minutes, and booed out of the venue.

China isn’t alone in setting high moral standards for their stars. Retired table-tennis star Ai Fukuhara was branded “selfish” and “flippant” by Japanese netizens after being spotted allegedly cheating on her spouse in March this year, and publicly apologized for her “reckless behavior.” At around the same time, several prominent South Korean pop and film stars were accused of having been school bullies—actress Seo Ye-ji was dropped by numerous brands she endorsed and by the upcoming K-drama Island over the allegations.

Why do East Asian fans take such transgressions so seriously? A 2019 study from Erasmus University, Rotterdam, sampled 15 well-educated Chinese respondents from both genders and a variety of ages, from eight different regions. All respondents expected celebrities to “fulfill social responsibility.” The study concluded that although the state had no clear guidelines on celebrity behavior (at the time), the collectivism of Chinese society, as with most East Asian cultures, played a substantial role in driving public ire toward misbehaving idols.

A collectivist society emphasizes the duties of an individual with social influence. “To put it simply, [citizens] have a responsibility toward society, and if you’re famous then you have more responsibility,” says Sun Jiashan, a researcher of fan culture at the Chinese National Academy of Arts. Traditional kinship bonds extend into wider society (hence why it’s acceptable to call a stranger “auntie” or “uncle”), and historically, authority figures were not just doing a job, but acting as a “parent” with the duty of guiding the populace. “Celebrities are supposed to represent the best of the industry, so they are expected to take on a level of responsibility to match” their high position and salary, according to Sun.

Tradition is now being combined with Western concepts of celebrity in numerous East Asian cultures. Hollywood-style stars with big personalities and public presence are now placed in positions of social power, while social media has allowed fans unprecedented access to celebrity private lives. “The Chinese celebrity industry has been working in recent years to exploit the imaginary social relationship between celebrities in the mass media” as a way to boost sales and online traffic, according to Lin Ping, a researcher on pop culture at Beijing’s Capital Normal University. Fans are encouraged to view a celebrity as their lover, spouse, or trusted family member.

“The problem is, in Chinese society, family and intimate relationships often bring with them an excess of control and intervention over another person’s private life,” Lin tells TWOC.

Shows that portray celebrities in this light include Tencent Video’s Let Go of My Baby, a reality series broadcast from 2016 to 2018, where several male idols spend time looking after small children. For 27-year-old Yang Yuchen, the show was the reason she began to follow 20-year-old Jackson Yee of the boyband TFBoys. “He was so patient and was a caring brother. All those babies loved him. That was really impressive,” she tells TWOC.

Since then, Yang has bought products Yee endorses and even tried to get tickets to his birthday celebration in Shanghai, which were sold out within seconds. Yee is a “good role model in my life,” says Yang. “He does really well in his professional undertakings…He’s also involved in many public welfare projects.” For Yang, it's important for idols to model good behavior as “fans or followers may imitate them.”

Online celebrities now have to tread carefully lest their real private self jars with their public image or renshe (人设) in Chinese, short for renwu sheding (人物设定, character setting). In the past, Yang stopped following several male celebrities (whom she declined to name) when she found they had committed adultery. “Maybe it was because they pretended to be good husbands on screen,” she says.

In January this year, fans were shocked and outraged by the Tibetan influencer Tenzin (Ding Zhen in Chinese), beloved by millions in China for his innocent, untarnished rural persona, expertly puffing on an e-cigarette in his hotel room. Two days later, Tenzin’s studio issued a statement: “Smoking is a personal choice of adults, but public figures must pay attention to their public influence. Mr. Ding Zhen apologizes and calls on everyone to care for their health and not to smoke.”

Public scandal, though, isn’t guaranteed to bring down a celebrity. Actor “Michael” Chen He is widely believed to have had an extra-marital affair back in 2015, cheating on his wife (and childhood sweetheart) Xu Jing with big-name actress Zhang Zixuan on the set of a TV show. When he was announced as a guest on Season Two of the female-centric idol show Sisters Who Make Waves in September of 2020, the hashtag #BoycottChenHe started trending on Weibo. Chen’s role in this year’s Spring Festival box office hit Hi, Mom also led moral crusaders to call for a boycott on the film in the comment sections on review site Douban (later taken down by the site), on the grounds that Chen is a “cheating scumbag.” But despite netizen anger, Chen still gets regular film roles—and Hi, Mom still made Chinese film history as the highest-grossing female-directed movie of all time.

Although state regulators have not set explicit rules for celebrity behavior, they are keen to publicize and moralize on celebrity misbehavior to promote core socialist values. Shortly after Zheng Shuang’s downfall the China Association for Performing Arts, a trade union backed by the government, published a series of measures to ensure entertainers “abide by social morality.”

The guidelines are unprecedented in giving a detailed blueprint for regulating performing artists’ actions, both on and off camera. Artists who commit dark deeds like drunk driving, gambling, drugs, pornography, and violence, and other acts “that violate ethics and morals” will be blacklisted from working with association members and banned from taking part in promotional activities for a period of one year to a lifetime. There are also some guidelines of a political nature, such as “love the motherland,” “support the Party’s line and policy,” and “consciously practice the core values of socialism.”

To resume work, blacklisted artists must apply to an ethics committee three months before the ban ends, and those approved will enter a rehabilitation program that might include vocational education and public welfare projects to restore their public image. It isn’t clear how effective this list will be at bringing about change, however, given that previous attempts at industry clean-ups didn’t prevent Zheng Shuang repeating Fan Bingbing’s misdemeanors.

A combination of government regulators and public anger can result in successful cancellation on a case-by-case basis. “Firstly, there has to be a large enough level of public anger at a celebrity’s actions,” says Chen Caiwei, a former producer at Tech Buzz China and co-founder of Chaoyang Traphouse, a newsletter on internet culture. “But then the public are often waiting for condemnation from a government body, which is the green light to release full-on cancellation.”

Another factor is proof of guilt: There are videos of Li Xiaolu and PG One kissing, and Zheng Shuang was damned by the leaked recording, whereas no one has found ironclad evidence—shichui (实锤, “solid hammer”) in Chinese social media parlance—of Chen He’s transgression to date.

But the damage inflicted by netizens’ cancel culture can be a heavy burden. Both Li Xiaolu and her ex-husband Jia Nailiang have claimed the scandal damaged their mental health. “My family was almost destroyed,” said Jia in a Weibo post, relating how his parents had been “crushed by rumors” and were afraid to leave the house, while his little girl came down with a fever (which he links to the pressure the family faced). Li wrote on Weibo condemning the endless online abuse by “piranhas” over the winter of 2018, and indicated suicidal thoughts. Zheng’s cancellation was so thorough that she was even temporarily blocked from using food-delivery app Meituan. “Murderers on death row [now] have more rights than Zheng Shuang,” noted one Weibo user.

For now, Yang takes a protective stance over her idol Jackson Yee, telling TWOC that if Yee aroused public anger, “I will tell people around me to please give him some time and that I trust he will be back on the right track very soon.”

On the other hand, she feels some violations of basic moral principles are non-negotiable. “If Jackson Yee acted in a similar way to Zheng Shuang, I definitely would have approved of him getting similar treatment,” says Yang. “People like [idols] because they are outstanding in some aspects, but that doesn’t give them an excuse to do something bad.” The higher you climb, it seems, the harder you can fall.

Additional reporting by Hatty Liu

The Moral Burden of Being a Chinese Celebrity is a story from our issue, “Something Old Something New.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.