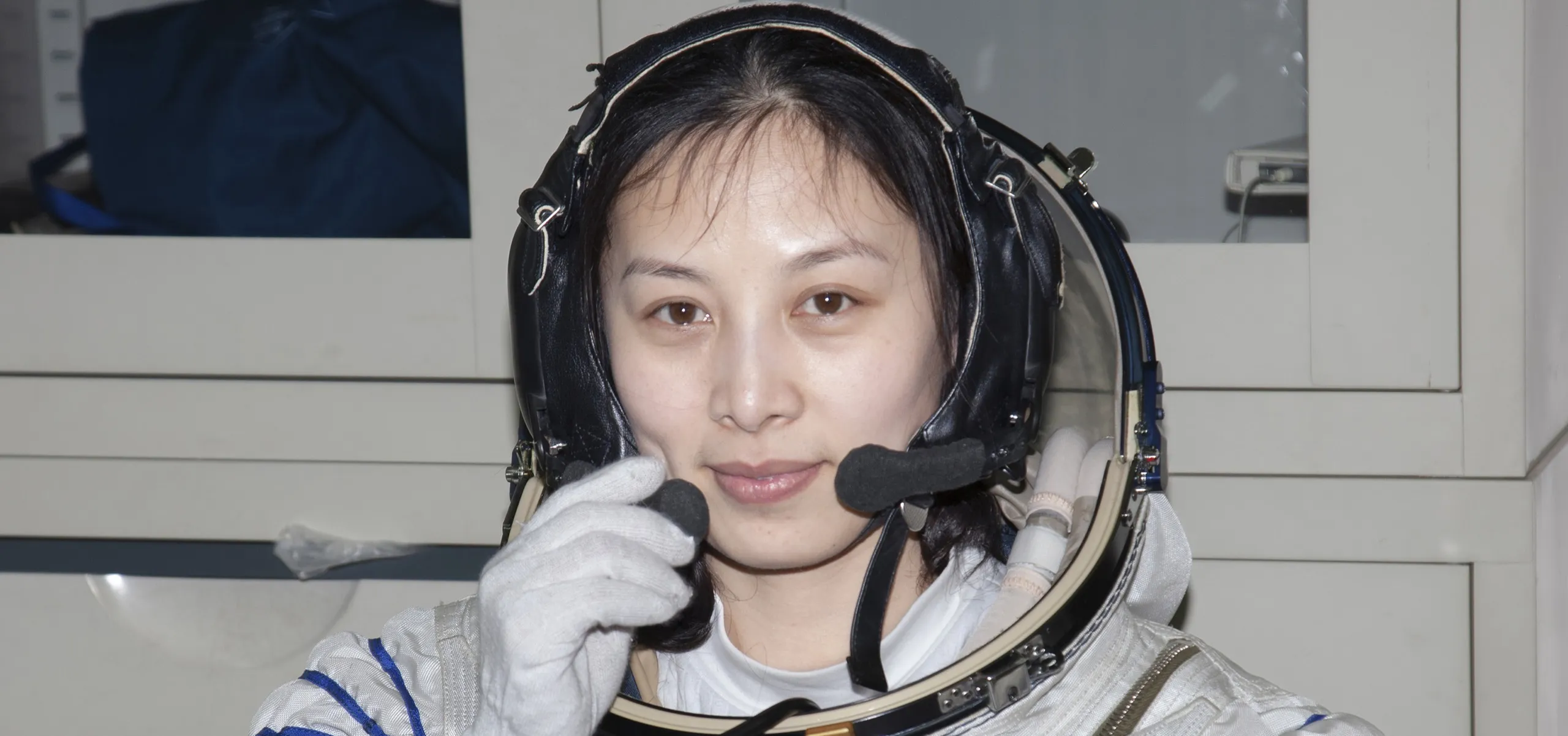

Domestic media coverage about Wang Yaping, the Chinese space station’s first female astronaut, includes talk of cosmetics and sanitary pads

At 12:23 a.m. Beijing Time on October 16, the Shenzhou-13 spacecraft blasted off from Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwestern China’s Gansu province, and successfully docked with China’s Tiangong Space Station six hours later.

Despite achieving several historic milestones for China’s space program—for example, the 183 days the crew will spend in space represents the longest duration in orbit for Chinese astronauts; twice that of the Shenzhou-12 mission completed last month—the mission has attracted the most attention for sending a female “taikonaut” (Chinese astronaut) to work on the space station and take a spacewalk for the first time.

Ever since the crew was first announced and made their public debut in Jiuquan on October 14, 41-year-old Wang Yaping has attracted far more media coverage than her male colleagues: 55-year-old Zhai Zhigang, the commander of this mission and the first Chinese to perform a spacewalk 13 years ago; and 41-year-old Ye Guangfu, a newcomer to space. CNN hailed the launch “a landmark moment for female astronauts and the country’s rapidly expanding space program,” while retired American astronaut Cady Coleman, who made a six-month stay on the International Space Station in 2010 and 2011, extended her well-wishes to Wang in a video, “When you look out the window and you see the stars and the Earth, billions of women will be looking out that window with you.”

Wang’s career path from the Shandong countryside to outer space has made her an inspirational figure. Part of the online discussion, however, soon segued to focus on representation of female professionals in media, as news reports highlighted how cosmetics were included along with feminine hygiene products and health supplements the space mission had shipped to Wang in space, along with other stereotypical items like chocolate and desserts.

The hashtags “Tianzhou-3 [cargo spaceship] sent cosmetics to the female astronaut” and “Female astronauts can apply cosmetics on the space station” had received 26 million and 110 million views, respectively, on the microblogging platform Weibo at the time of writing. According to Xinmin Evening News, the zero-gravity environment, closed space, and radiation on the space station is harmful to astronauts’ skin, making it age faster and become more susceptible to infections and allergies. The cosmetics, consisting of toner, serum, and cream, were made by a Shanghai-based company that has worked with the Astronaut Center of China since 2015, and also provided products for the all-male crew of the Shenzhou-12 mission earlier this year, according to news site The Paper.

While many netizens applauded the space program's consideration for astronaut well-being, some took umbrage at their excessive focus on the topic in Wang’s case, echoed in media coverage. Some netizens were particularly infuriated by the statement that female astronauts “may feel better psychologically after applying cosmetics,” by Pang Zhihao, a spaceflight researcher and former analyst at the China Academy of Space Technology, in an interview with China News after Shenzhou-13’s launch. To some extent, this controversy is part of the growing debate in Chinese society on female representation, gender norms, and gender-based equality in the workplace.

The current mission is Wang’s second spaceflight, after her first one in the Shenzhou-10 mission in 2013. She is China’s second female space traveler, after Liu Yang, a member of 2012’s Shenzhou-9 mission. Ever since Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin entered space in 1961, men have dominated the field of space exploration worldwide. According to NASA, as of March, 65 women have flown in space, including astronauts, payload specialists, and space station participants, compared with 500 men. Only 15 out of all 225 spacewalks in the last 60 years were performed by women, with Wang’s slated to be the 16th.

The world’s first two female astronauts, Valentina Tereshkova and Svetlana Savitskaya, who went into orbit in 1963 and 1982 respectively, were both supposed to be the Soviet Union’s “political weapon.” In the US, NASA did not admit women into its astronaut training program until 1978, and sent its first female astronaut and astrophysicist, Sally Kristen Ride, into space three years later. 2013 saw a new record of four female recruits to NASA, equaling the number of male recruits for the first time in history. But the percentage of male recruits overall ranged between 74 and 89 (mostly over 80), before 2013, with the latest figures in 2017 showing men were 55 percent of all recruits.

Female astronauts currently account for 10 percent of all astronauts in the world, according to Pang, which is also the case in China’s space program—two female astronauts and 19 males—though the latest recruitment information from June of this year has not been released. Begun in 1992, the China Manned Space (CMS) program, also known as the “921 program” after the date of approval by the central government, recruited its first 14 astronauts from over 1,500 pilot candidates in 1998, who were all males. It recruited its second batch of trainees, including Liu and Wang, in 2010. Since 2003’s Shenzhou-5 mission, which saw Yang Liwei become the first Chinese in space, 14 taikonauts have traveled to space.

Wang, who became a pilot in 2001 upon graduation from the Aviation University of Air Force in Changchun, Jilin province, told the state-run Xinhua News Agency this October that she was inspired by Yang’s 2003 space trip. “China has male and female pilots. Now that we have male astronauts, when will we have female ones?” she said were her thoughts at the time.

There is still division of labor down gender lines in the profession, according to experts. Most female astronauts are mission specialists responsible for tasks within the spacecraft. Pang alleges this is due to the “the biological and mental condition of female astronauts, such as a higher percentage of body fat, smaller average stature, lower weight, and slower metabolism” that make them less suitable for becoming pilots. Similarly while discussing the cancellation of NASA’s first all-women spacewalk due to an insufficient supply of medium-sized spacesuits in March 2019, NASA administrator Ken Bowersox made clear the ideal astronaut body is still male, blaming women’s smaller average stature for making them less able to “reach in and do things a little bit more easily.”

Yet Pang notes—and Wang has confirmed in interviews—that there is no difference between the recruitment and training regimen applied to male and female astronauts. NASA scientist Dr. Randy Lovelace, who had conducted the official physicals for America’s first manned Mercury 7 spacecraft, had also concluded that females astronauts who receive the same training as males outperformed their male counterparts on many metrics, based on his tests involving 25 female aircraft pilots between 1959 and 1961.

Even proponents of greater inclusion of women in space exploration tend to highlight differences between the sexes, and make their case according to gender norms. In a 1962 US congressional hearing intended to challenge NASA’s exclusion of female astronauts, Jerrie Cobb, one of Lovelace’s test subjects and the first female astronaut candidate in the US, declared based on supposed scientific findings that women are “less susceptible to monotony, loneliness, heat, pain, and noise than the opposite sex, [which are] vital facts…for space exploration of increasingly longer duration." Similarly, Pang cites unnamed scientific studies to state female astronauts make “more acute observers, more considerate problem-solvers, and better communicators…and fit better for long duration in space.” According to Pang, Wang Yaping “can bring more vitality to the crew, help the team work more smoothly and efficiently, and make more complete space medical experiments [on women].”

Even Wang made similar comments: “A manned space program without female astronauts would be incomplete...It is like a woman’s role in the family. Women have responsibilities. We also make serious missions more lively and pleasant,” she told CNN. With women gaining visibility in the field, the question of how their competence and professional skills are portrayed will become more and more relevant when, as pointed out by space studies scholar Alice Gorman in Cosmos magazine, “The future of space may be female.”