A new film by Guangxi-born director Yang Xiao bends an ear to the region’s dying tradition of ethnic folk ballads

For many Chinese people, the thought of folk songs from Guangxi evokes the legend of Liu Sanjie, a peasant girl of the Zhuang ethnic group, standing in a fishing boat and singing melodiously toward the southwestern region’s green hills.

The image persists today thanks largely to the efforts of the local tourism industry, which has sponsored everything from a popular 1960 film about Liu to a show staged every night by the picturesque Li River. But it’s exactly that stereotype that director Yang Xiao is rebelling against in his new short film, The Mountains Sing.

Yang, a native of the mountainous city of Guilin, previously directed the internationally screened shorts Chronicle of a Durian (2017) and Dancing Together (2015), while also racking up assistant director credits on award-winning productions like Bi Gan’s Kaili Blues. His latest work, a 40-minute documentary, received a special mention at this year’s FIRST International Film Festival in Xining.

The Mountains Sing chronicles the endangered singing traditions in remote Zhuang villages, where groups of men and women gather to sing improvised lyrics in dialogue with one another. Perhaps this makes them all the more valuable, an oasis of constancy amid a sea of change, real estate development, and poverty alleviation programs slowly encroaching upon their homeland.

Yang spoke to TWOC via the messaging app WeChat about his initiation into cinema and the inspiration behind his work. The interview has been edited for brevity.

How did you discover your passion for filmmaking?

I have loved drawing since I was a kid, but I was also tormented by the dogmatic system of graded art exams in schools. Over time, this hobby transformed into a desire to imitate the mannerisms of my friends, classmates, and teachers, or to draw them as caricatures.

As a teenager, the pressure of the gaokao [China’s grueling college entrance exam] made me hide in rock music. I didn’t know what I wanted for my future, except to make independent music and find meaning in my search for meaning. But the gaokao was approaching, and no [Chinese] universities taught rock music.

One day, I read about Chinese “indie films” in So Rock magazine. That term and the dark, hazy posters shocked me and made me think there was a parallel world to indie music. But my real enlightenment was [Chen Kaige’s acclaimed 1984 drama] Yellow Earth, which completely overturned my perception of film.

Until then, I had dismissed cinema as something that served propaganda or commercial purposes and had nothing to do with art. Yet Yellow Earth used basic elements like framing, spacing, light, and shadow to compose poetry about noble lives [during China’s turbulent 1930s and ’40s]. This majestic view of history blew my mind and convinced me that film could simultaneously satisfy my needs for sight, sound, and thought, needs that are both mutually dependent and reflective.

What prompted you to make your first film, Everlasting Violence?

That was a feature film I made at the end of high school. At that time, I knew nothing about filmmaking. I just wanted to express my grievances about the education system, and had quite a few friends who were also into films, so we made it. That’s the advantage of being young: I had only learned three guitar chords before I started a band. It’s when you grow up that you start to agonize over gains and losses.

The total budget for Everlasting Violence was no more than 1,000 yuan [155 USD], and we had a film-screening at a small bar in my hometown and made more than 2,000 yuan from the screening. Now that I think about it, it’s a miracle.

You’ve suggested in previous interviews that different creative forms are all means to the same end. You’ve said that “writing and filmmaking are essentially the same thing,” and compared the role of a director to that of a DJ. Can you elaborate on that?

I tend to talk nonsense on the fly. If asked the same question the next day, I might give the opposite answer. What I say depends on the specific context.

As for comparing a director to a DJ, that was specific to the approach [to The Mountains Sing]. However, I partly agree that while all art may not have the “same end”—after all, the starting point of contemporary art is rebellion against the “same end”—it always develops in dialogue with elements of the era in which we live, such as technology, digitization, ecological crisis, and identity politics. No creators today can claim that their experiences and creations are separate from that.

Can you explain the meaning of the Chinese title of The Mountains Sing,《欢墟》?

In the Zhuang language, the term 欢墟 or haw fwen means folk song gatherings. Haw means singing, and fwen refers to the marketplace where men and women would gather to sing.

I should explain that the Zhuang people have no written script, and [after 1949] a Latin script was invented based on the phonetics of the Zhuang language from the Wuming region, but the local vernaculars can be very different and even mutually unintelligible.

The main reason for choosing this word as the film’s title is the sense of conflict formed by these two Chinese characters. They not only evoke a pleasing image of “having fun amid the ruins,” but also suggest the structure of the film: The first part is about 欢, which literally means “joy,” as at a lively folk song gathering; the second part is about 墟, [literally] “ruins,” a modern society built from rubble.

Like many of your works, The Mountains Sing explores the boundary between reality and fiction. Why have you previously said there is no clear distinction between documentaries and feature films?

Although media archeologists may disagree, [the 1896 documentary] Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat is popularly considered as the origin of cinema. That means documentary is the archetype of film medium. The leviathan on the screen, and the shocking experience of watching it, combined to create the film. What this documentation brought to the audience was not the reality, but the strangeness of the hyper-real.

In this sense, documentaries are not about reality. They are fiction that goes straight to the heart. The sense of reality that we perceive in documentaries is constructed through narrative, editing, sound, and lighting.

In The Mountains Sing, the construction site and the cave are not actually in the same place, but I really wanted to create some association between the two, so they were juxtaposed. There are countless examples of fictionalization like this. I think that every documentary contains fictional, transcendental elements.

You have emphasized the concept of “heteroglossia” in explaining the sound and music treatment of The Mountains Sing. What do you mean by that?

Heteroglossia, or polyphony, is a theory proposed by [the Soviet literary critic] Mikhail Bakhtin for Fyodor Dostoevsky’s literature. It’s an important characteristic of Zhuang folk songs. Men and women sit in groups under big trees, on paths between rice paddies, at the mouth of caves, in groups of two or three. They serve as each other’s background wall of sound and construct an undulating, wavelike soundscape. For this reason, Guangxi is nicknamed the “Sea of Songs,” which I find very accurate.

Heteroglossia is also a characteristic of all public space, including the internet. It’s both decentralized and pluralistic. It contrasts with top-down, monotonous official discourse that, in the case of the Zhuang, is represented by the [state’s] progressive discourse of poverty alleviation. Heteroglossia is both the film’s method and its attitude.

Four More Must-See Movies

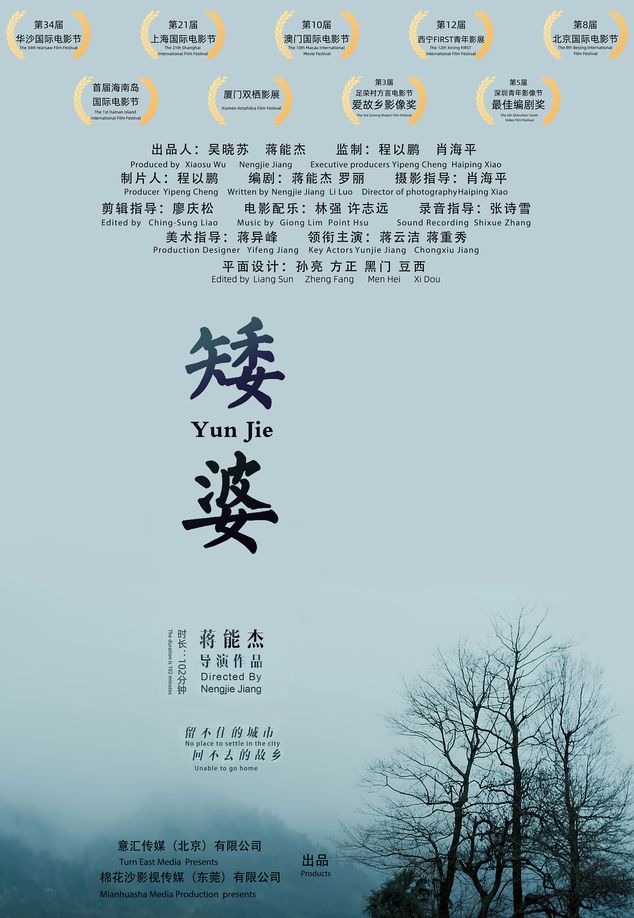

Yun Jie

The fiction feature debut of director Jiang Nengjie, previously known for documentaries, is a paean to China’s 60 million “left-behind” children. The 12-year-old Jiang Yunjie lives with her grandmother and two younger sisters in rural Hunan province. A bright and sensitive child, she balances schoolwork with helping support the family. When she helps her grandmother in the fields and then falls asleep in her exam from exhaustion, she is chastised and told that her low scores suggest little academic promise. Meanwhile, Yunjie’s friends begin dropping out of school to find work in the city. A coming-of-age story, Yun Jie premiered at Beijing International Film Festival in 2018 and is finally getting a theatrical run.

Remembering 1950

“If you came a few days later, maybe I would no longer be alive,” an elderly woman, who served in the Chinese army in the war in Korea in 1950, says to the camera. This big-budget documentary collects the oral histories of 26 elderly Chinese veterans, many of whom have never granted interviews before, who share their stories of sacrifice and survival on the battlefield in Korea. Even as the patriotic tones of the film run high, the individual stories of ordinary fighters are emotionally honest and self-contained. Many audience members have hailed the documentary a tearjerker.

Invisible Alien

When a Chinese space base receives communications from what they believe to be an alien civilization, a spacecraft with 93 crew members is dispatched to investigate, and then disappears. Now, 150 years after its disappearance, the spacecraft reappears in Earth’s orbit, and the sole survivor—Captain Yuan’s lover, Yin—recounts the harrowing tale of what happened. A suspense-thriller interweaving state-of-the-art computer graphics, Invisible Alien is an achievement for the growing body of Chinese science fiction movies.

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings

The first Asian superhero to enter the Marvel universe, martial artist Shang-Chi confronts his past—and his father—when recruited by the Ten Rings organization. Highly anticipated for its global all-star cast, this blockbuster film puts young Chinese American actors like Simu Liu and Awkwafina beside the established Hong Kong legend Tony Leung and Malaysian star Michelle Yeoh, as well as Chinese actress Meng’er Zhang and British actor Benedict Wong. It is also the first Marvel film with a director of Asian descent, Daniel Destin Cretton.

– Tina Xu (徐盈盈)

This is a story from our issue, “Upstaged” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.

The Mountains Sing: Yang Xiao on Documenting Guangxi’s Fading Folk Music is a story from our issue, “Upstaged.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.