Fierce, majestic, tame: Depictions of tigers have changed over centuries in Chinese art

“Even the tigers know you can’t be happy when you don’t know when the pandemic will end,” one Weibo user commented on a post about the controversial “depressed”-looking tiger stamps released by China Post this January for the upcoming Year of the Tiger, winning thousands of likes on the microblogging platform.

The two stamp designs, named “Prosperous Nation” and “Auspicious Tiger,” depict “an inspiring tiger that climbs high and looks into the distance” and a gentle tiger mother with her two cubs, to convey good wishes to the nation and all families, for their prosperity and happiness, China Post claimed on its website. However, many netizens complained that the tigers look anxious and not like the majestic, brave, or mighty symbols these big cats generally are in Chinese tradition.

In response to the criticism, the 72-year-old artist, Feng Dazhong, stated that animals could show a variety of emotions. Some art experts also pointed out in an interview with the Changjiang Daily that the tigers on this year’s stamps, painted in the “claborate” style (a common style in ancient Chinese art using fine brushwork to make realistic images), were more realistic compared with the stamps released in previous Years of the Tiger since the 1980s. Tigers have appeared in Chinese art works and ritual objects dating back to the Neolithic Age, and have taken on a variety of appearances and symbolism throughout the centuries—not always as the majestic or ferocious “king of all beasts.”

According to archaeological findings, such as a clamshell pattern of a dragon and a tiger unearthed in Puyang, Henan province, in 1987, the history of tiger worshiping can be traced back at least over 6,000 years ago in China. Honored as “the king of all beasts,” which represents bravery, strength, and authority, tigers have been featured on various objects, such as bronze ware and jade and gold ornaments. Some of these symbolized the owners’ status, such as the tiger-shaped tokens, or “tiger tallies (虎符 hǔfú),” used in ancient China to command troops.

Compared with the imposing tigers on those ritual objects, folk art works often depicted the big cats as cute and sprightly. Paper cuttings, clay figurines, and articles of everyday use incorporated tigers in order to help people dispel evil spirits, prevent disaster, and bring good luck.

When it comes to paintings, however, some creations have gone against those conventions, and featured sad, sick, weak, or docile tigers.

For instance, the painting “Awaking Tiger (《醒虎图》)” by an unknown artist in the Five Dynasties (907 – 960) depicts a huddled tiger with tears in its eyes. With little information about its creator and background, the work is believed to depict a tiger overcome by sleepiness.

Similarly, a famous work by artist Shi Ke (石恪) from the same period, features the Buddhist monk Fenggan (丰干) from the seventh or eighth century dozing on the back of an equally sleepy tiger, which is as meek as a cat.

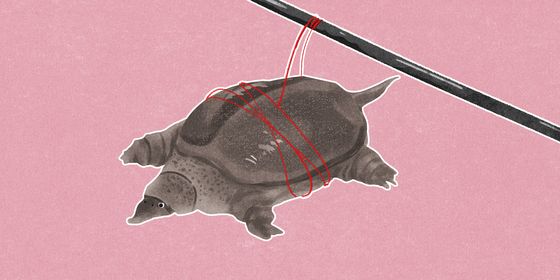

A more popular work of this kind may be the “Wasp and Tiger (《蜂虎图》)” by Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) painter Hua Yan (华喦), which is now kept in the Taipei Palace Museum. The thin and pitiful-looking tiger raises its paw to its head, anxious to ward off the attack of a wild wasp. In an interview with Yangzhou Daily this January, Liu Nanping, former president of the Yangzhou Chinese Painting Academy Art Museum, suggested that the painting reflected Hua’s own life. Drawn in Hua’s later years, the tiger embodies the painter, whose great talent went unrecognized for most of his career.

Perhaps, then, Feng’s depiction of the sad tigers was not such a break from tradition after all. Indeed, some netizens agreed that the tigers on the stamp are “realistic.” As one popular comment on Weibo reads, “The tigers I’ve seen at the zoo bear the same expression.”