Young, middle class collectors are bending China’s art market to their own tastes

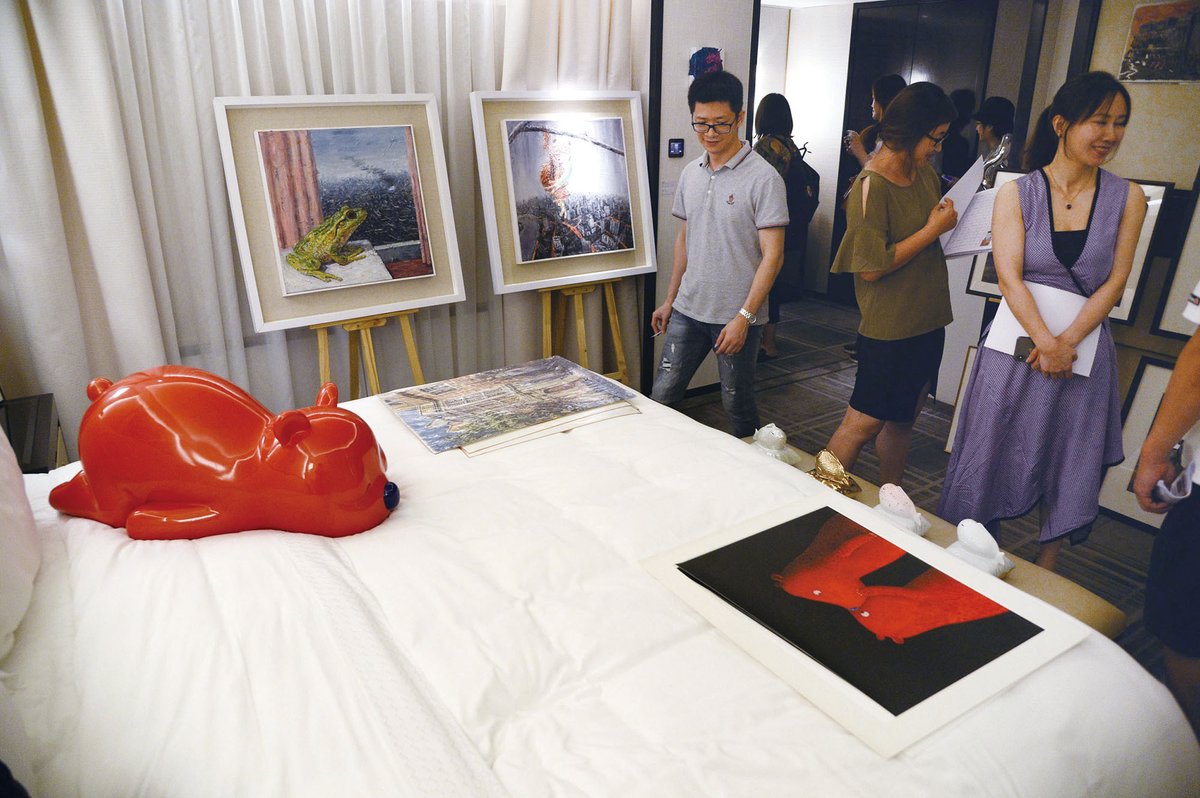

Every summer, the fifth floor at the five-star Peninsula Hotel in the heart of Beijing transforms for a weekend-long extravaganza. A few dozen suites open their doors to visitors who walk in to discover colorful diptychs above headboards, abstract sculptures on window sills, glittering jewelry in drawers, and ceramic figurines by bathtubs, all curated by galleries who temporarily occupy these suites as their booths at Art Fair in Hotel (AFIH).

Unlike most art fairs, where galleries promote and sell their works inside convention centers, “AFIH feels more approachable,” Wang Di, a visitor, tells TWOC, “Although there are expensive items, the overall vibe is more like hawkers selling paintings.” While some price tags show a longer string of zeros, the fair has a wide selection of items priced between a few hundred to a few thousand yuan, affordable to those who might not want to spend more than a fraction of their monthly income on these works.

According to AFIH’s survey in 2021, 55 percent of the fair’s visitors identify themselves as white collar workers, part of a rapidly growing demographic of middle-income individuals who now make up 30 to slightly over 50 percent of China’s population, according to various definitions including from China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

These individuals, who earn 500,000 yuan (80,000 US dollars) per year, are largely urban, past worrying about necessities, and tend to have funds for non-essential spending such as travel, entertainment—and now art. While they might not be striking headline-making bids at art auctions, they are slowly forcing the art market to adapt to their demands.

Once a novelty, art fairs have mushroomed in China, and galleries are adopting strategies to cater to newcomers. Dayu Yang, Founder of Beijing gallery PIFO, told Artsy, an online art trading platform, that the gallery made an effort to bring small-scale works to Art021 Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair, including a painting that sold for 4,000 yuan (about 650 US dollars).

For admirers of big-name artists, economic alternatives exist. For those who can’t afford original works by the Chinese-French painter Sanyu (1901 – 1966), whose oil painting Goldfish sold for more than 170 million Hong Kong dollars (about 22 million US dollars) at a 2020 auction, prints of Sanyu’s works are sold at art fairs for 10,000 to 50,000 yuan (1,500 to 8,000 US dollars). These licensed, high-quality reproductions of paintings satisfy collectors’ need for both originality and scarcity. “A lot of living artists now accept this form. So do galleries, which might help [painters] find good printing studios to work with,” says Ashley Qin, an employee of an online art trading platform.

However, some differences of opinion still exist. “In the West, prints are a [widely accepted] form of art,” Xu Mengchen, an independent art advisor, tells TWOC, “whereas in China some [buyers] might associate prints with [cheap] replicas and have prejudices against them.”

One of the most popular sections in auctions nowadays, “trend art (潮流艺术),” also contributes to the rise of the middle-income market. A classification coined in China, the term “trend art” has no exact definition, but encompasses a wide range of artworks and artists, usually colorful, bold, and figurative. Works that found their way into this section include Japanese artist Takashi Murakami’s kaleidoscopic murals of smiley faces and American designer Kaws’s clown-like figures.

In an interview with Hi Art magazine, art collector and critic Mao Zhuang summarized a few features of trend art: The artists incorporate pop-culture elements into their works, interact frequently with fans on social media, and collaborate with trendy brands to produce merchandise. The merchandising aspect is further blurring the boundary between trend art and consumer goods: If Daniel Arsham’s plaster sneaker sculptures and Jeff Koons’s balloon dogs have a place in museums, then there are good reasons to count Adidas x Arsham sneakers and miniature balloon dog pendants as artworks, too.

AFIH features small, reasonably priced oil paintings and sculptures suitable as home decoration (VCG)

Other partitions are slowly dissolving as well, spurred by the pandemic and the expanding clientele. Traditionally, collectors like to see works of art in the flesh, but galleries and auction houses are now embracing technologies that help them establish their presence in the virtual world. “Online viewing rooms” facilitated by art fairs use augmented reality for clients to browse works in gallery settings and interact with artists.

Galleries and auction houses are also creating a copious amount of relatable content on social media. The Chinese auction house Guardian’s WeChat account, for example, features an article titled “How many steps does it take for a newbie to become an emerging collector?” which gives tips including “focus on the media you like” and “buy an artwork as a reward for yourself.”

A significant number of galleries and auction houses have also partnered with online sales platforms active in China, including Artsy, Yitiao’s online auction platform, and online auction app ArtPro. These digital tools allow users to buy or bid with a few clicks and to access the price database of past sales, which brings some transparency to the market that can appear esoteric to buyers without expert knowledge or prior experience. “Five years ago, there just wasn’t a possibility to do art sales online,” says Qin. “But now, putting works on [online] platforms or into online viewing rooms shows that [galleries] are open to welcoming new collectors to join the game.”

Apart from the size of their wallet and the amount of collecting experience, high net worth and middle class individuals might take different approaches to their purchases. According to a number of sources in the art industry, the former, often professional collectors, might be more concerned about the growth potential of artworks’ market value, while middle class, amateur buyers tend to prefer works that they identify with.

“Some professional collectors put their purchases directly into tax-free storage facilities and might not even look at them before the works change hands to another owner,” observes Qin, “whereas [middle-class buyers] might take a more personal interest in the artworks, because they often purchase them to decorate [their living space].”

TWOC spoke to a Shenzhen resident in her mid-20s who is pursuing a career in consulting about her decision to collect her first artwork after visiting an art fair. “At the time, my family was renovating our apartment, so I thought about buying a painting that would match it,” she shares with TWOC, preferring to remain anonymous.

After learning about artists through galleries and consulting friends who work as art advisors, she decided on a work by Chinese artist Wang Tiande, who is known for his innovations on Chinese ink painting and calligraphy. “He uses incenses to burn [paper surfaces] in order to create,” she explains, “The process of destruction is given a new life. I like that idea.”

Others have taken an alternative approach to harvest an artwork’s aesthetic value. China has long had a robust market in making copies of artwork, with “painting workers” in Dafen village in Shenzhen well-known for supplying homes, hotel chains, and other businesses around the world with replicas of famous oil paintings. These days, hundreds of venders on Taobao, where copyright is not the priority, are ready to render onto canvas any work desired by clients, with prices calculated based on the image’s complexity and the canvas size.

A Shanghai-based designer educated at China Academy of Art, who does not want to be identified, saw a large 1-meter-by-2-meter painting at an art fair that impressed her with its opaque green and blue colors. But the painting, priced around 150,000 RMB (about 25,000 US dollars), was well beyond her budget. “So I took a photo of it and sent it to a painting supplier that I work with and ordered a copy [for a few hundred yuan],” she says.

The painting now hangs in the living room of the designer’s Shanghai apartment, and she seems surprised when TWOC asks her whether she sees a difference between her copy and the original. “What do you think? The difference is of course the money.”

Collecting Trends: How Middle Class Buyers Influence China’s Art Market is a story from our issue, “State of The Art.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.