Read the second part of the story of Xu He as she leaves the leprosy village—and find out why she comes back

Read Part 1 of the story here.

After being separated from her family at age 12 by traffickers, leaving her in-laws’ village, and wandering the streets of Guangzhou before being sent to a new government-run leprosy hospital for treatment, Xu He is finally reunited with her father and ready to resume her normal life. Find out what’s in store for her in the next 60 years of her extraordinary life.

6 / 9

After Xu He came home, her father wouldn’t allow her to do heavy labor out of concern for her health. She did household chores instead, looking after her younger brother, who was only a few years old at the time. One day, Xu He was by the doorway when she saw a woman heading up the mountain to gather firewood. Wanting to add to their own stocks, she followed the woman up the mountain. After she was done chopping, she bundled up the firewood and left it by the door. But her father got angry when he saw this, telling her not to do it again.

At Xinzhou, the doctors were always reminding patients to look after their fingers and toes. Because leprosy causes nerve damage, they lacked feeling in their extremities. By the time they noticed a burn or cut, it was often already quite serious. But working at the hospital, they frequently handled rough bricks, thorny wood, and knife-like grass—how could they not get hurt? Xu He would rinse the cut, bind it with cloth, and go right back to work. Long accustomed to ignoring her injuries, Xu He was touched by her father’s anger, because it showed that he cared about her.

However, the real obstacle between Xu He and her “homecoming” was the hukou system. At the time, staples such as rice, salt, and oil had to be bought using coupons, which were alloted by the state according to each person’s residence permit. Xu He’s hukou was still registered under her mother’s in the countryside, while her father’s permit was in the city. In order to stay with her father, Xu He would run down to the police station after eating each day and ask, “Why must children be separated from their parents? I am my father’s child, why can’t my hukou go with him?”

Each time, the answer was the same: “Yes, children do stay with their parents. But yours is a rural permit, so you have to go back to the countryside.”

How could she return? Xu He was a single woman fresh out of the leprosy hospital, with limited function in her hands and feet. How could she live on her own? Would unfamiliar villagers take her in? And, of course, she didn’t want to leave behind the father she had gone to so much trouble to reunite with.

But the regulations were black and white. Once, when Xu He went to buy flatbread, the cashier refused to sell to her. The two of them got into a big fight. Three people’s ration coupons were not enough to feed four; Xu He did her utmost to find ways to reduce her burden on the household. She would run errands or do household chores for her neighbors in exchange for a few meat tickets or rice.

Her father and stepmother didn’t say anything, but she didn’t want to make their lives harder. She started quietly planning—maybe the only path remaining to her was to return to the leprosy hospital.

A fellow patient from Xinzhou came to visit Xu He, and told her that a new “Taihe Hospital” in Guangzhou was now taking patients. Perhaps she could try to get admitted there, where she would be closer to her family.

So Xu He went to Taihe, a township to the north of Guangzhou, and told the hospital director that she was homeless. By all accounts, she was already cured and couldn’t be admitted. But maybe the director took pity on her, or the hospital needed new hands to work—in any case, her application was approved.

Taihe was 30 kilometers from Xiaobei. The transit system was still rudimentary at the time, so every trip home was an ordeal. There were two or three days each month that her father and stepmother had to take a night shift at work. On those days, Xu He would take leave and come home to watch her younger brother. It was a long way from Taihe to the bus station, and the road was deserted. Concerned for her safety, a wardmate would bring her to the bus station on the back of her bicycle each time, and meet her at the station each time she returned.

In the 60s, the roads were made of yellow dirt and people’s clothes were blue and gray. Xu He sat on the back of that bike, swaying to and fro as she traveled across the city. It was only after her family relocated from Xiaobei that she stopped going to see them.

Only two months had passed since Xu He left Xinzhou. She was back in a leprosy hospital, this time for good. Taihe became her longest home.

7 / 9

Taihe Hospital, also known as Taihe Village, gets its name from its location in the town of Taihe. It was officially known as the “Guangzhou Dermatology Hospital,” a name that lives on in worn characters written above the main entrance.

Like other leprosy hospitals, Taihe is located off the beaten track. A path led to the foot of Maofeng Mountain, where a few mud huts with thatched roofs were initially built. In 1974, the government built the Helong Reservoir here. The hospital entrance opens directly onto a watery vista.

Xu He was part of the second cohort to arrive at Taihe. The hospital was cold and deserted, with only about 10 residents. As new waves of patients arrived, the population reached a peak of over 500. In this once-desolate setting, these few hundred patients built themselves a little world.

The villagers had a funny saying: All of the mountainsides facing the hospital were theirs. They lived off those mountains—it was the source of wood for their houses, branches and leaves for tinder, as well as a place to plant bamboo groves and raise chickens and fish. They grew melons and vegetables. They built a brick kiln, roads, and houses, and dug ponds. The hands that had been so tenderly protected at home now needed to do all manner of heavy labor.

They received 9 yuan a month for food, with two vegetable dishes for each meal. The money they got from working wasn’t even enough to buy a hat with. But unlike at home, Xu He at least had her own share of food coupons. The first time she received the coupons, she bought half a kilogram of sugar and half a kilogram of biscuits. She made herself a bowl of sugar water and ate the biscuits in one sitting—keep in mind, this was her share for the whole month. When the other patients saw her, they fell over laughing. Some of them joked, “Having an appetite sure is a blessing!”

Xu He, having eaten her fill, said contentedly: “Of course it’s a blessing. When there’s food, you eat, and when there’s not, you figure it out.”

This was the wisdom she had gained from her past 30 years—you never knew what the future would hold.

There were far more men than women at the hospital. Xu He had good looks and an easy-going nature. Now with her belly unladen and body light, she took a fancy to a man surnamed Liang.

A year younger than Xu He, Mr. Liang was also from Guangzhou. His life had been just as complicated as hers. He was born into a poor family and sold himself into another family as a son. But that family resented him for eating too much, so he ran off to join the army. While in the army, he found he had leprosy, and around that time, he’d just gotten married. His wife died in childbirth, so he had no choice but to give his daughter to his mother-in-law and enter the leprosy hospital.

Old Liang was not particularly good-looking; the leprosy had left the corners of his mouth crooked. But he had a good heart. Her whole life, Xu He had a soft spot for two kinds of people: those who suffered hardships, and those with kind hearts. Adding in that she had twice been helped by soldiers when she was homeless, she naturally felt a kind of intimacy with them.

But back then, the law explicitly prohibited those with leprosy from marrying. Any relationship had to be carried out in secret. If caught, the lighter consequence was discipline, the more serious was expulsion from the hospital.

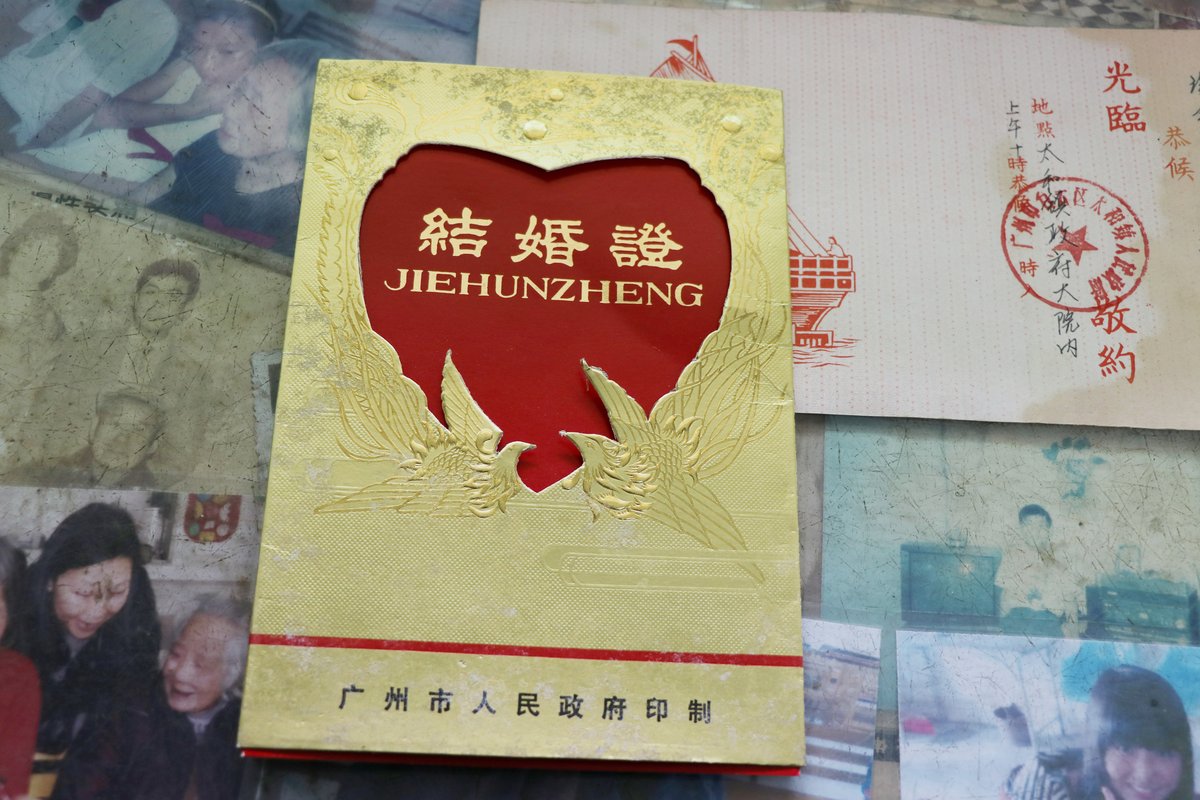

It was only in 1985 that a new marriage law lifted the ban. Taihe told its now middle-aged patients they could have a marriage ceremony. In 1987, the hospital acquired marriage certificates for ten couples, including Xu He and Mr. Liang, and hosted a joint ceremony for them. Aside from one couple that had already been married, the rest had met in the hospital. The day of the wedding, each couple was given new pillows, sheets, and plastic chairs. Wearing red flowers pinned on their chests, they received their blessings in the auditorium.

Xu He and Mr. Liang were a good match. After marriage, they never bickered. After a few years, the hospital built new quarters on flatter ground, reserving the row closest to the entrance and dining hall for the married couples. It was called “Yuanyang Row.” Not long after moving in, Old Liang took a fall outside their house. He’d suffered a stroke, and became hemiplegic. There were no home care workers back then, so Xu He did it all: Feeding him, bathing him, washing his clothes, cleaning up after him. Old Liang was paralyzed on one side, so Xu He would roll him over on the bed, panting heavily the whole while. She never complained, although she was already losing function in her hands.

Xu He spent half of the marriage taking care of her bedridden husband. One day, a few years later, she had just finished feeding Old Liang a breakfast of boiled eggs when his body seemed to give out. By the time the doctor came in, he had already passed. All Xu He could do was go on without her husband—but she did keep their wedding photo up on the wall.

Old Liang had a good friend in the hospital called Mr. Lai. Their friendship went back several decades. Mr. Lai was blind and had an amputated leg; he often went around with aluminum crutches, moving with surprising speed. After Old Liang died, Mr. Lai bought some paper money and burned it with Xu He. From then on, he helped Xu He out whenever he could. She got carsick easily and rarely went out, so every morning Mr. Lai would take an electric wheelchair to the market three kilometers away to do her shopping. He’d often bring her back a rice noodle roll. The two of them would often chat outside their houses. Often times, they’d talk about Old Liang, and they’d say, “He really was a good man, and a hard worker too.”

It was also during those years that Xu He’s younger brother called to say her father had passed away. But it was a long way away, and Xu He didn’t go back for the funeral. She had gotten carsick since she was young, and it had only gotten worse the older she was.

The trees planted back when Yuanyang Row was first built—palm, papaya, longyan—grew taller and taller. And gradually, the men among the couples housed there began to die. It was always the women who lived longer, who clung on to life.

—

Just like that, the 90s were half over, and one of Xu He’s friends was leaving the hospital. This friend wanted to transfer to another leprosy hospital called Jinju in Dongguan. Xu He had heard that a fellow patient from Xinzhou had taken a minor leadership role at that hospital, so she went along to put in a good word.

Xu He was carsick the whole way, arriving at Jinju with her head spinning. Just as she was talking to her old friend from Xinzhou, the friend suddenly pointed out a middle-aged woman, saying, “Hey, that’s your deaf girl!”

Xu He was surprised and delighted. She walked up to the woman and called out her name. At first, the deaf woman didn’t recognize her, looking at her blankly. That’s when Xu He made the motion of scrubbing her back with a washcloth, meaning: Don’t you remember? I used to help you take baths?

With that, Ahnü finally recognized this “adoptive mother” from over 30 years ago. Radiating excitement, she tugged furiously at Xu He’s hand, wanting to take her home to eat. But Xu He couldn’t leave her friend, so she waved her hand saying, next time. Ahnü seemed a little put out, sticking out her bottom lip.

It was only at this meeting that Xu He learned of all that had happened since the two had parted ways in 1960. Ahnü had stayed at Xinzhou until it closed in 1975, after which she was transferred to Jinju. There she married, and had two daughters and a son. The son had fallen into a pond when he was young and drowned, while the daughters were already in their teens. Ahnü’s husband had fallen gravely ill. When on his deathbed he had begged a friend to take care of his wife, so this friend became Ahnü’s second husband.

Around this time, a Hakka woman heard of Ahnü’s life story and came to claim her as kin. She said she was Ahnü’s mother, that she had left her on the streets after finding out she had leprosy. Ahnü didn’t have any recollection of her childhood, and took the woman at her word. She gave this woman the tens of thousands of yuan she had saved in over a decade raising chickens at Jinju. But as soon as the money changed hands, this “mother” disappeared without a trace.

When Xu He heard this, she felt both anger and pity. She said, “You fool, do you believe everything people tell you?” Ahnü had no comeback for this. She only blinked her eyes, looking like a child again.

The anger didn’t last, but the delight was real. Xu He took heart at being able to find the girl she had taken care of several decades apart. It was hard for Ahnü to go out, so despite her carsickness, Xu He went to Jinju twice to visit her. After Xu He lost her ability to walk, Ahnü’s husband began bringing her to Taihe on visits. During the Lunar New Year of 2018, the couple bought a padded floral jacket for Xu He, purchased meat and vegetables, and made her a meal in the dining hall.

On the Lunar New Year of 2019, Xu He waited and waited, but Ahnü and her husband didn’t turn up. She had no mobile phone, and couldn’t get in touch with them. When I came to visit in April of that year, she told me about this. I knew a social worker at Jinju, and was able to get the phone number of Ahnü’s husband. When we called, he explained that he had had surgery last year and spent several months at the hospital. Come next spring, he would be sure to bring Ahnü to see her adoptive mother. Xu He couldn’t stop saying yes—it was only after hearing this news that she was able to put her heart to rest.

After the phone call, Xu He took out her padded jacket for me to see. She also rummaged up a photo she took with Ahnü. Sitting next to the bed, head bowed, she examined the woman with graying hair standing next to her in the photo. After a while, she seemed to suddenly notice something astonishing. She laughed and said softly, “Look, Ahnü is already so old…”

Ahnü was 70, and a grandmother. But in Xu He’s eyes, she was still that skinny 10-year-old who would look up at her, who had bundled up her clogs and clothes and begged through tears to go with her on the day she left.

At the time, none of us could have anticipated the pandemic that would arrive the following year. And so the promise that Ahnü’s husband made to see Xu He was never fulfilled.

8 / 9

Gradually Xu He’s world began to shrink. Eventually, she couldn’t even go to the dining hall across from Yuanyang Row. Sometimes, charities would organize trips for everyone at the hospital. Xu He couldn’t go, so she would sit outside and watch them leave early in the morning, see the calm settling over the village. At dusk they’d return, chattering and full of energy. Night would fall, and another day would be over.

Leaving aside her physical health, Xu He was quite satisfied with her life at age 90. She didn’t need to work anymore, and the government provided a monthly stipend, while kind-hearted people would donate them supplies. This was baffling to her, as someone who had once carried 50-kilogram loads of bricks every day in exchange for six work points. How could life be so good? It was a pity she could no longer eat like she used to—she’d already lost all her teeth, so when she ate she could only suck on the food to get some flavor.

But Xu He continued to live happily. She had a stash of Shuanghongxi cigarettes a care worker had bought for her, and kept them on her table. She could smoke two packs a day. Since she couldn’t use her fingers anymore, she had to put the cigarette in a special bamboo tube. Another constant companion was the little blue packets of painkillers she took to reduce the nerve pain and rheumatoid arthritis that came along with leprosy. The instructions say to use three packets a day, but Xu He said, “When the pain gets bad, I take at least 10 packets a day.”

When people get old, their whole world changes: Floorboards are as slippery as ice, spoons and scissors jump aside like they’ve grown feet, bodies feel like top-heavy rag dolls, and feet like cotton. Before Old Liang died, Xu He could take a machete up the mountain and bring home a bundle of firewood. Now, she couldn’t even tie her own hair up or hold a comb, so she cut her hair.

Due to the long years of manual labor, her fingers shrank and curled up year by year, until she was left with a pair of fists with only the thumbs distinguishable.Sometimes when she sat quietly outside in the corridor with others, she would look down and see her withered stumps resting on her knees. She’d lift her hands gently and say, “Oh, how did these damn hands become like this?”

She wasn’t really waiting for a response—only mumbling to herself, bewildered at the turns of her fate.

She became reliant on the help of care workers and neighbors, which made her feel guilty. Wanting to do spring cleaning before the Lunar New Year, she tried to stand on her bed and clean the cobwebs off the ceiling with a broom, but she lost her footing and fell. She used an aluminum walker to move around her room, but because she didn’t have strength in her hands, she could only push the walker across the floor, making an ear-splitting screech. At night, she wanted to turn off the light switch by the door, but didn’t want to wake her neighbors with the walker. So she gingerly felt her way to the door, supporting herself on furniture. She ended up falling and getting purple bruises on her arms.

Feeling trapped in her body, Xu He started to think of death. She didn’t want to keep waiting. She asked the worker responsible for distributing meals whether they might be able to get her some rat poison—there were too many mice in the room. The worker refused, saying that mouse traps would be sufficient. She knew that the worker had guessed her intentions, so she let it drop. She could only keep on living.

Death was like an old friend with an unpredictable temper; it really was impossible to guess when it would come. She was envious of Mr. Lai. His old illness had flared up at 90 and taken him suddenly. No need to suffer, and no need to be a burden to others.

She started sleeping less and less, as if saving up for her eternal rest. She lay awake many nights. Then she would fumble upright and turn on a little yellow lamp, light a cigarette, and sit at the edge of her bed.

During her sleepless nights, she would think back to the day she parted from her mother in the countryside at age 12. That was the begining of her life. In all her decades she’d been adrift, she had never been able to find her mother and younger siblings. Her sixth uncle later told her that, in the end, starving, her mother had walked to the edge of the well to draw water, and fallen dead. “Why didn’t you look after her?” Xu He demanded in her grief. “I couldn’t even look after myself,” her sixth uncle had said.

At the foot of the mountain, Taihe was so quiet at night you could hear the wind blowing through the dense trees. Xu He sat lost in her thoughts in the still dark of night until a dry leaf fell from the palm tree outside her window, jolting her out of her reverie.

9 / 9

As a witness to Xu He’s twilight years, I hoped she could live a little longer. I was 23 when I met her—the same age she was when she was homeless beneath the clock tower. Over the next three years, I took down her oral history. I would come to Taihe every few months to spend a few days visiting her. Our relationship was built over the course of daily interactions and meticulous record-keeping.

Before every visit, I would call the director at Taihe to confirm that Xu He was still alive.

In the fall of 2018, I was sick of taking public transit, so I biked the 30-some kilometers to Taihe. I left in the afternoon, and it was already dark by the time I got to Taihe. The streetlights were dim, and truck after truck whizzed by on the provincial highway. As I turned onto an unlit village road, my tires slipped and I took a bad fall. I pulled myself upright and saw a nasty gash on my elbow.

The next morning when I saw Xu He, I didn’t mention my fall. But she told me that, not long ago, an older man had taken his electric wheelchair out and suffered a fatal collision with a truck on the highway right outside the village gates. After this, Taihe started providing three meals a day to the elderly in order to reduce the frequency with which they went out.

The residents at Taihe needed electric wheelchairs because of the amputations they had due to leprosy. This frequently put them in the blind spots of truck drivers, and made them invisible to this rapidly developing society. To die in a traffic accident after surviving everything else in their lives—it seemed like a cruel joke.

Due to her mobility issues, I was always thinking about what I could do for Xu He when I visited. For example, I might wrap the feet of her walker in cloth to reduce the screeching, wash her stained jacket, or comb her tangled white hair. When I cleaned out her ears, she sat still, the picture of contentment. She told me that when she had used scissors to pick her ears, she’d hurt herself, ending up with an earful of blood. In times like this, I would feign anger: “Come on, get someone to help you! Don’t do this to yourself!”

Xu He never troubled anyone with these little things, but was always delighted if you helped her with them. She sometimes asked me, “Why are you so considerate, always coming to see me?” I didn’t know how to respond, so I told her I came here on vacation.

It’s hard for me to describe how I cherished those times—just sitting there next to her, I felt an immense peace. When Xu He was still alive, Taihe was my spiritual home. We often sat together on the veranda, sunning ourselves. Xu He was tiny; she would sit with her hands on her thighs and her feet gently swinging in midair.

I liked to listen to her piecemeal recollections: How, when she was starving as a child, a landlord’s daughter once gave her a bag of rice; a memory from one of the hospitals when another female patient helped wash her hair with a tea-seed bar; or, when she took the bus with her mother into the city to see her father, she got carsick, and her mother gave her a Chinese olive to suck on and held her on her knee.

When we first met, she was in a stage where she could clearly remember her childhood while forgetting what she had for lunch. One time when I visited, I asked, “Do you remember me?” She said, smiling, that she remembered my face but not my name. The next time, I said, “I’m Ah Hong, do you remember me?” She smiled and said, “I remember your name, but not your face.”

All at once, I realized that she didn’t recognize me at all—she was just playing along.

It was only the day that I rode my bike to Taihe that she finally remembered me.

—

In the winter of 2019, I came to visit Xu He again. As I was preparing to leave on the third evening, Xu He called me into her room. She had me open the drawer of her bedside table and told me to take two bills from within. This was a game we played each time we parted. As always, I said, “I have a job, there’s no need to give me money.” Thinking that I had convinced her, I left the room to go wash my hands. When I came back, I saw that she had somehow moved herself from the bedside to where my backpack was. She was trying to slip the bills inside, cupping the two bills between her fists, trying to stuff them into the side pocket. When they fell under the chair, she tried again.

She was so focused she didn’t notice I had already returned. I rushed over and caught her hand: “You really don’t need to give me anything, it doesn’t cost much to come here…”

She glared at me, “Do you want me to to live to 100?”

I said, “Of course, but…”

“If you do, then take it!” Xu He didn’t let me finish.

Then Granny Yao from next door shouted, “It’s getting dark out, why haven’t you left yet?” The residents worried that it would be dangerous for me after dark; they started urging me to get going at 4 in the afternoon. Hearing this, Xu He stuffed the bills into my hand. I didn’t know what else I could say, so I embraced her and told her I’d come back and visit her again after the New Year.

One of the caretakers gave me a ride to the newly-opened subway station five kilometers away on his electric scooter. We made our way through heavy traffic as night fell. The highway was full of trucks, the sound of their horns never-ending. We left Taihe in this cacophony.

That was the last time I saw Xu He.

—

Two months later, in the spring of 2020, the coronavirus pandemic broke out. The leprosy village was closed to visitors—even family members of the patients.

Even after the pandemic came under control that summer, Taihe remained closed to the public. I waited at home until July, when I heard from a caretaker that Xu He was severely ill. Unable to wait any longer, I called a Taihe doctor in a last-ditch attempt to visit.

“Sorry, that’s not possible.” The doctor’s response wasn’t unexpected. “The city health department says we must be especially careful in nursing homes, leprosy hospitals, and such. Even doctors like us need to quarantine for 14 days to go in. You can have her come meet you at the entrance instead.”

“But Granny is bedridden and can’t come to the entrance,” I said.

“If she can’t walk, you can have a caretaker set up a video call instead.” He responded quickly, as if he’d had this kind of conversation many times already.

After hanging up, I stood frozen in the alley for some time. The caretaker sent me a photo. The person in it was shriveled and pale, like a sheet of paper. I didn’t dare ask about Xu He’s condition again.

Xu He passed away on the last day of September. Her illness had dragged on for three months. Maybe her will to live was too strong, her body hardy like a weed. This wasn’t the death Xu He had hoped for, nor was it the farewell I expected. She never saw Ahnü again, and I never saw her again either. All of her things were cleared away and burned, which I regretted deeply. I didn’t have a single memento of her—no letters, photos, marriage certificate, or old food coupons.

The day after I received news of her passing, I slept until noon. Upon waking and opening the front door, I was greeted with brilliant sunshine. In the dazzling light, a black butterfly danced through the air toward me before flying away again. I was shocked: Back home, they said that black butterflies were the spirits of deceased loved ones. Was this Xu He coming to say goodbye?

A year later, after I had stopped crying whenever I thought of her, I wrote down Xu He’s story. Sometimes I wondered what she thought about in her last days. Did she dream of her long lost mother and siblings? Did she dream of Ahnü when she was little, struggling to climb up the bed? Did she dream of me? Of the warm afternoon sun in Taihe in April?

We spent many such afternoons on the veranda, with the mountain breeze blowing, leaves rustling, and the filtered sunlight dancing brightly. She would sit next to me, swinging her legs—innocent as a child, seemingly never-aging. When she talked about herself at age 12, about her long and storied life, it was like it all happened yesterday. It was as if the sunshine separated us from all the suffering and regret of life, never to touch us.

Written by Hong Mengxia (洪梦霞)