From wandering the streets to living in a leprosy colony, an ordinary 93-year-old woman recounts an extraordinary century of life

Few people know that a “village” for leprosy patients has existed at the foot of Maofeng Mountain in Guangzhou for over 60 years. Even five years ago, it wasn’t marked on any digital maps.

The hospital, with its 30 elderly residents, is so quiet it doesn’t feel like it’s in the city. Sunlight streams down over the misty lake by the entrance. A few people are fishing from wooden rafts, like in a painting. Papayas, palms, camellias, azaleas, and osmanthus are scattered throughout the village. Some of the villagers are drying radishes in the sun, while others are ambling back from the field with vegetables they’ve just picked.

The first time I met Xu He was on New Year’s Day in 2017. By then, she was 90 years old and no longer able to work. She sat on the porch, bundled in a thick winter coat. Tiny in stature, she had a big belly, snow-white hair, and a toothless smile. Even though she was no longer able to leave her room unaided, she was cheerful when she spoke, with clear recollections of events from decades past.

When I walked up to her and asked her to talk about her life, she didn’t hesitate. She began her tale with a sly remark: “Let me tell you, I even sold myself to traffickers!”

The contrast between aged body and her carefree, childlike demeanor sparked my curiosity. What had happened over the course of her almost century-long life?

This old woman was like a riddle. But as her story unfolded, I came to see how certain pivotal events of her life had left their marks on her.

1 / 9

Xu He was born in 1927, the oldest child of a poor peasant family from the north of Guangzhou. Her mother stayed home to farm, while her father labored year-round in the city. Every year, her father would come home and her mother would get pregnant again. Just like that, Xu He ended up with seven younger siblings.

In her earliest memories, Xu He was already working. When she was little, she would go out to the fields with the adults to harvest sweet potatoes. When she got older, she herded cattle for other families and gathered dry branches from the fields and slopes to use as firewood.

In 1938, the Japanese army arrived. Troops occupied Guangzhou, and the battle came to Xu He’s doorstep. When the rice was ready to harvest, the Japanese enclosed the paddies with barbed wire. Unwilling to give up their harvest, Xu He’s uncle slipped into the fields with a basket. The Japanese soldiers caught him and shot him dead on the spot.

They had no harvest, and were cut off from the city. Due to roadblocks, Xu He’s father had no way of returning to the countryside, so her mother stayed home and suffered it out with her eight children. They would forage wild water spinach and boil it plain, without even a drop of oil. Occasionally they’d boil some rice. Xu He would take the liquid from the top to drink and leave the porridge for her younger brothers and sisters.

After half a year, the family was nearing the point of starvation. Xu He’s mother decided to chance an escape with the children to her own mother’s home in Foshan. She told them, your grandma’s hometown has a lot of millet—if we can get there we might not go hungry. She carried the youngest child on her back and took the hand of another, while the remaining children flocked along. Halfway there, they came upon the Japanese army closing the road under martial law. Stared down by dark gun barrels, the family had no choice but to turn back.

On the way home, her mother bought a few cucumbers—one per person—to serve as the day’s sustenance. They had no chance of making it back home before dark, so when they spotted a thatched hut by the road, they thought to spend the night there.

A strange woman saw this big family and came up to ask who they were. Her mother told the truth. After they finished talking, the woman pulled Xu He aside and quietly asked: “How about you come and be my girl?”

“Your girl?” Xu He didn’t understand. In Cantonese, this word, muiyi, could mean either “daughter” or “servant.”

The woman said, “If you come with me, you’ll have food to eat, sweet potatoes and taro.”

Twelve-year-old Xu He pondered this. She had walked all day with only a cucumber in her stomach—the temptation was great. But thinking again, she said, “I can’t leave my siblings without someone to look after them.”

“How about I give you some money in exchange?”

The woman offered her 20 copper coins. Hearing this, Xu He immediately agreed. She gave the coins to her mother after the woman left. Her mother asked where the money was from, and she only said it was from that auntie they saw earlier. She didn’t say that she had sold herself.

It was only the next day, when the woman came back for her, that Xu He came clean: “She’s taking me to be her maid.”

Her mother understood at once. Eyes welling up, she gave her consent. Xu He knew that her mother didn’t want to leave her. But with her eldest child gone, there would be one less mouth to feed, plus the 20 extra copper coins.

“Don’t forget to write home.” Her mother kept repeating this phrase, gazing at Xu He through her tears.

Xu He promised—at the time, she still didn’t know how to read or write.

—

The woman took Xu He on a boat at the bank of the Pearl River. They followed the river 100 kilometers north to a ferry in Wushi, Shaoguan. There they got off, and the woman turned right around and sold Xu He to a second person. It was only then that she realized she’d been tricked—the woman had never meant to take her as a maid.

Amid the chaos of war, abduction and selling children were commonplace. Xu He wasn’t the only child being sold at the ferry market. The adults swept appraising eyes over their tender faces and bodies, picking servants, temple attendants, or child brides for their families. A woman, after looking over several children, chose Xu He. She told the trafficker: “I want to take her home as my future daughter-in-law.” With that, she paid and bought her.

Having changed hands thrice, Xu He was adopted into a Hakka family as a child bride. Since she wasn’t yet old enough to marry, she slept with the woman who bought her. The woman told Xu He to call her “mother-in-law,” or jiapo. Jiapo was raising a son on her own; the boy was a year younger than Xu He. He spent most of the week at school, and would come home on Sunday night only to leave again the next morning. The first time she saw him at home, he was holding a small rattan rack full of books, and she mistook him for a barber. She asked, “Why is there a barber in our house?” The mother-in-law said, “That’s your husband.” Xu He was silent. She was so young—how could she know what a husband was?

Jiapo had bought Xu He not just as a future daughter-in-law, but also to work around the house. Every day before dawn, she would get out of bed and go barefoot to the fields. As she bent to transplant rice seedlings, she thought of her family. Did her mother and younger siblings get home safely? Have they found anything to eat? Would they survive? As these thoughts came to her, she straightened up and stood frozen in the field, stiff as a board.

Jiapo saw her stop working and asked, “What’s the matter with you?”

Xu He said, “Nothing, nothing’s wrong.”

“If nothing’s wrong why are you standing there? Get back to your transplanting.”

“I’m not transplanting anymore.”

Seeing this, Jiapo asked, “Do you want to go home and see your mother?”

Xu He nodded.

Jiapo gently coaxed, “Alright, get those seedlings transplanted first. When there’s no more work to be done, I’ll go with you to bring some sweet potatoes to your mother.”

Xu He took her at her word and went back to work.

Even though she had to work hard every day, she never went hungry, and Jiapo had a soft touch. When she felt sad thinking about her family, Jiapo would encourage her, saying that soon she would take her back home to see her mother. Coaxed along like this, Xu He was soon 16 and eligible to marry.

The family held a wedding feast. They bought pork, killed a chicken, and invited relatives and neighbors to share the meal. With that, the marriage was official. Xu He moved into her young husband’s room, but there was still distance between the two of them. Her husband only spoke Hakka; they couldn’t understand each other.

2 / 9

Some time later, Xu He noticed that her belly was gradually swelling. She rushed to ask Jiapo, “What’s happening? How could my belly be getting bigger on its own?”

Jiapo had her walk around, felt her belly, and said, “You’re carrying!”

What could this mean? Xu He was afraid. But her belly, aside from continuing to swell, caused her no trouble. The fear receded, and she went on working, eating, and feeding the chickens.

The days passed, and eventually it was long past the time she should have given birth. Her mother-in-law fretted, “Other people give birth after 10 months, how could it be that you still haven’t? How’s the child doing?”

Xu He said, “What child?”

“The child you’re pregnant with!”

“Things are okay, it doesn’t hurt or move.”

But now that her mother-in-law mentioned it, she remembered: Her belly used to move. She once tripped and fell while harvesting sweet potato leaves—it was only afterwards that it stopped moving.

Young Xu He didn’t give more thought to the child in her womb. Innocent to the ways of the world, she didn’t lose sleep over it. Jiapo might have guessed that the fetus was dead, but in the rural Guangdong of the 1940s, what could she have done? The war raged on around them, and survival was hard enough. Who was going to keep track of when a young rural wife was supposed to give birth?

The years passed, and a succession of flags flew over the city. Xu He was now 22. She suddenly noticed red spots springing up on her body like moss, circular patches appearing on her hands and stomach. Some neighbors took notice and started spreading the rumor that she had leprosy.

During her time with the Hakka, adults would always threaten children by saying, “Hurry up, the leper is coming!” One time, Xu He was working in the paddies when a man passed by. Someone said, “Here comes a leper!” A couple of people grabbed their carrying poles, chased him down, and beat him. Xu He was disturbed by this: “That man did nothing wrong—he was only passing by, why would they beat him? It’s truly evil.”

But she never thought that this universally despised disease might fall upon her. What could she do? She despaired, I’ve never been around anyone, how could I get this disease?

The thought came to her that it might be better to drown herself—the family lived very close to Qujiang town. During the day, she snuck off to the riverbank alone. She gazed into the water, struggling to come to a decision. If it really was leprosy, she would die a clean death. But if it wasn’t, then wouldn’t she have died for nothing?

So she didn’t jump. A few days passed, and she was wishing for death again. She cried the whole way to the river, where she stood at the edge of the dock. But she just couldn’t jump, so she cried her way home again.

The red spots on her body persisted. In spring of 1951, when her condition seemed to have stabilized, Jiapo took her to the big hospital in Qujiang for an examination. It was her first time in a hospital, and it made a deep impression. She watched the doctor use a knife to cut a piece of flesh from her finger, gently stick it on a piece of glass, and look at it through a lens. “It’s leprosy.”

“She came here so young, how could she have leprosy?” Her mother-in-law couldn’t believe it. Back then, people said that you could only get leprosy by sleeping around. But Xu He had grown up under her watch.

“So it really is leprosy.” Xu He was dumbfounded. “What do I do? I better go, then.”

“Go? Where would you go?”

“Back to Guangzhou.”

“And what would you do there? People fight to live, not to die!”

When the two of them got home, the news of her diagnosis had already spread throughout the village; there was even talk of burying her alive. When Xu He learned of this malicious plan, she ran up to the hilltop to look. Sure enough, a few men were digging a pit. Furious, she ran down to them and asked, “What are you getting at here?” The men said, “You’re a leper now, so we’ll give you two choices: Leave, or die. Your call!”

They also said that if you bury someone and pour quicklime on top, it’ll disinfect the grave. Xu He knew quicklime from using it as a fertilizer: When she touched it, a layer of her skin would come off.

As if aware of Xu He’s plight, Jiapo killed a capon and stewed it just for her. Blinking back tears, she said, “Come, eat, you won’t get to have food like this in the future.” But in her despondence, how could she eat?

That night, as everyone was sleeping, Xu He snuck out of the house alone. She spent the night hiding in the dark mountains. At first light, she followed a pig seller’s cart to the train station. But she had no money to buy a ticket. She was lucky—a kind-hearted soldier saw her crying by the roadside. After hearing her story, he bought her a ticket to Guangzhou.

3 / 9

After leaving the Guangzhou train station, Xu He asked around for directions. Somehow, she found a shop her father had taken her to when she was young. The shop matron told her, your dad returned to the countryside long ago. Xu He also wanted to go back, but she had no money for a ticket. She stood on the street and looked around, at a loss as to what to do.

The shop wasn’t far from the “Big Bell Tower,” a once-flourishing landmark on the Pearl River. Built in 1916, the tower was 30 meters tall with a 13-meter belfry. It tolled every quarter hour, and on the hour it played the Westminster Chimes. The music could be heard from five kilometers away. In the spring of 1950, the Kuomintang still flew planes out of Hainan and bombed Guangzhou, damaging the bell tower. The tower wasn’t repaired until the following July.

When Xu He arrived, there was no Western music telling the time. She saw some beggars gathered at the foot of the tower and added herself to their number. But with no experience begging, she couldn’t get anything to eat. Perhaps taking pity at the sight of her belly, a kind woman with a blind husband gave Xu He some of the food she begged. This went on for a couple weeks, until Xu He couldn’t impose any longer. She said, “How about this—you give me the supplies, and I’ll beg for myself.”

The woman gave her a clay bowl and a pair of chopsticks, telling her: “See those people standing in front of the shops? You should go over and stand with them.”

Xu He took the bowl and walked down the street. She saw two men standing outside a restaurant, one on either side of the door, and went over to them. She tried to strike up a conversation, but they ignored her. After some time, a woman came out of the shop with two big bowls of rice and gave them to the men. There was nothing for her. Xu He asked, “Auntie, is there any more rice?” The woman glanced at her. “You’re begging too? Where are you from?”

Xu He said she was from the countryside. As soon as the woman heard this, her tone changed. She scolded, “You villagers all got your share of land after liberation—you must be a lazy good-for-nothing to be out here begging so young!”

At the time, Xu He knew nothing of the land reforms being piloted in the countryside around Guangzhou. She didn’t dare mention her leprosy, so she could only run back to the foot of the bell tower with her empty bowl. She squatted there and wiped her tears, her cuffs drooping to expose one of the red patches she’s been trying to hide. At 23, with her long hair in a bun and a swollen belly, she still didn’t know how that little red patch would change her destiny.

—

The kind woman continued to give Xu He a portion of the food she begged. Half a month later, they heard rumors that the People’s Liberation Army was coming to clear out the homeless and keep them from sleeping on the streets. In the early days of liberation, it was common to “clean up” a city’s appearance. Rough sleepers were dragged off to work in state-run factories, while those too young to work were sent to children’s homes. One way or another, there was always a place to go. The beggars decided to leave the bell tower and hide out in the alleys for a few days. The woman urged Xu He to come along, but Xu He wouldn’t go—if they took her, it would at least be better than roughing it outside.

Sure enough, the army came. A soldier came up and asked Xu He about her situation. She didn’t hide anything, saying that she had gotten leprosy and fled the countryside. The soldier didn’t seem convinced. He had her walk a few steps, but she had no limp; he had her extend her hands, but she wasn’t missing any digits.

Xu He was wearing a long-sleeved dress, so the red patches on her arms and legs were covered. There was only one spot visible on the back of her hand. The soldier still didn’t quite believe her. He took her to the hospital for an examination, where leprosy was confirmed.

He said, “Alright, let’s get you on the boat.”

“Are you putting me to death?” Xu He asked.

“No, we’re taking you to get treated.”

Was it too good to be true? Half-believing, Xu He followed them onto the boat. As soon as she got on, two soldiers flanked her, saying they worried that she might fall. Xu He said, “No need to pull me, I’m not going to jump in.”

As they went along, the landscape grew more remote. She saw crumbling buildings on river islands overgrown with weeds. The further they went, the more anxious she felt. She asked, “Is this where they do ‘target practice’?”

The soldier said no, it wasn’t.

Xu He said, “Look at how tall the grass is! And you’re saying this isn’t a shooting ground? I’m okay with dying, but don’t try to fool me!”

The soldier was caught between anger and amusement. “It’s not, I promise we’re not going to kill you. What have you done to deserve that? Thieves, murderers, and arsonists are the ones who get used for ‘target practice,’ stupid!”

Having been tricked by human traffickers from a young age, Xu He wasn’t reassured. But she was already on the boat—there was no turning back, and nor could she jump overboard.

At last, 50 kilometers upriver, they pulled to shore. The soldier said, “We’re here.” Xu He got off the boat and looked around. “There really is a big hospital, how bright and beautiful! So they really were telling the truth.”

This little island, totally unknown to Xu He, was on the Dongjiang river in Shijie, a township in Dongguan city. Encircled by the river, the island was covered in reeds. Several two-story buildings rose from the lush vegetation.

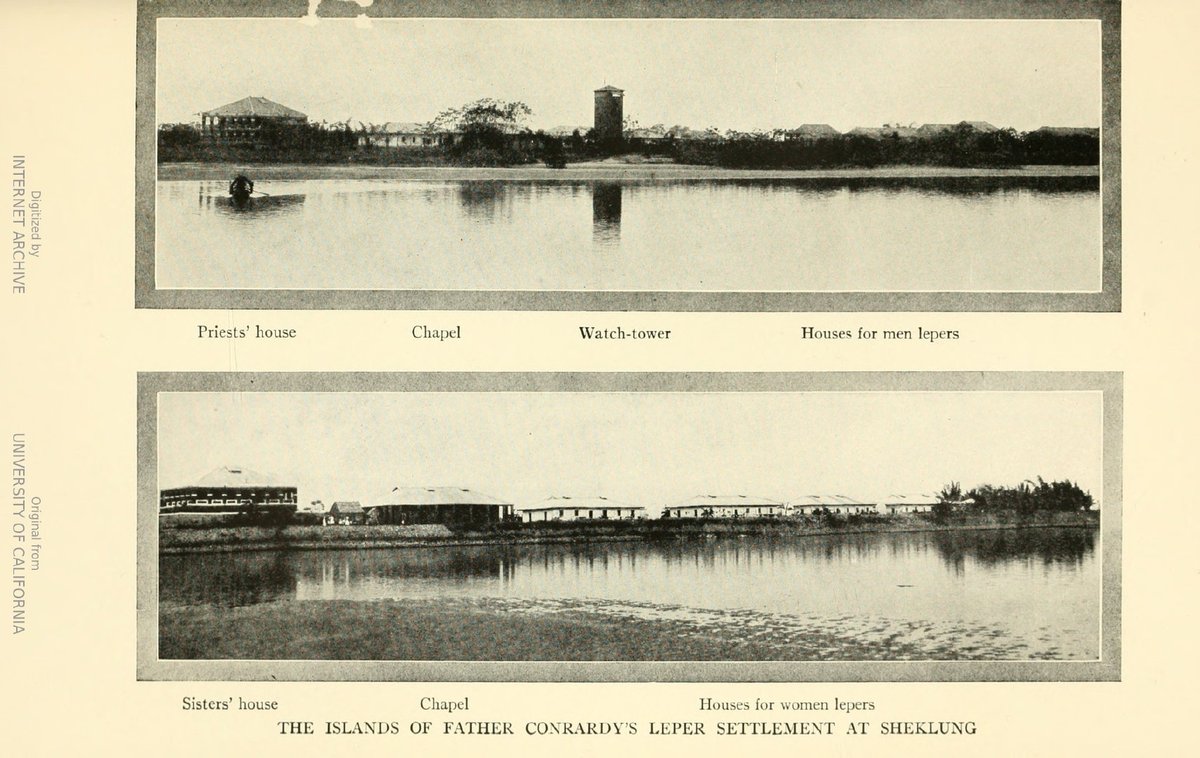

This was the “Joseph’s Island Hospital,” built in 1907 by Father Conrardy, a Parisian priest from the French Foreign Mission. The hospital housed homeless leprosy patients. When she arrived, the hospital was run by foreign doctors and nuns. Although the nuns were covered head to toe and spoke in an indecipherable patter, she found that these “foreign devils” were much kinder to leprosy patients than people on the outside. The nuns didn’t fear or shun her. If a patient was hurting, they would go straight up and feel their skin with bare hands.

Back then, there were around 300 patients living on this scenic little island. This was Xu He’s first time seeing so many leprosy patients of all walks of life: male and female, old and young. Under the nuns’ management, men and women were strictly separated. If she wanted to go buy something from the kiosk in the men’s quarters, she had to make a request. The women occupied four wings, each with 40 residents. The bottom floor was for cooking, and the upper floor for sleeping.

“You have to try to live, not to die.” Xu He remembered these words from her mother-in-law. Carrying a child that floated between life and death, she stayed in the hospital. Like a grass seed tumbling onto the island shore in the wind, water, and sun, she somehow survived.

4 / 9

At the end of 1951, the Guangdong provincial government took over the hospital and “invited” the nuns to leave. Reluctant to see them go, the patients gathered by the riverbank and tearfully begged them to stay.

The nuns were weeping as well. “We don’t want to go either, but your government wants us to go, so we must.”

By then, Chinese doctors had already established themselves in the hospital. Seeing their tearful patients, they said: “Don’t cry, we Chinese can take care of ourselves better than the foreigners can.”

This was true—they were in fact the best leprosy doctors in Guangdong at the time. The government put the hospital under the supervision of the health department and changed its name to “Guangdong New Island (Xinzhou) Hospital.” The resources they had were the best in the province.

After the government took over the hospital, Xu He fell sick. The doctor prescribed her Western medicine, instructing her to take one pill after a meal. When she was little, she had always been given a dark liquid herbal medicine when she was sick. The pills were smaller than her finger. She didn’t understand how one could be enough. After the doctor left, she decided to swallow an entire packet of pills. Not long after, she started shivering uncontrollably. The other patients quickly wrapped her in blankets, but even so, she couldn’t stop shivering. The woman in the bed across from her ran to fetch the doctor. The doctor came, gave her an injection, and saved her life. “And where’s the medicine I gave you?” he asked. Xu He said, “I ate all of it.” The doctor was gobsmacked. “No wonder! No more of this in the future—however many I tell you to take, is how many you have to take.”

The story made its rounds in the hospital, and for a time, Xu He was a laughingstock. From then on, she followed the doctor’s orders.

—

The provincial government funded several rounds of improvements to the hospital, including new wards, staff quarters, and additional medical facilities. The hospital also organized the patients into farming and brick-making units so they could work while they received treatment. Xu He started working in the brickworks.

In 1953, villages started to be organized into “mutual aid teams.” The hospital followed suit, allocating “work points” to the patients and dividing them into several tiers according to the difficulty of the job. Xu He could only do third-class labor, carrying bricks from the kiln to shore and then onto a boat for six work points a day.

Back then, the bricks were larger than the ones used today. Freshly fired bricks were around 4 kilograms each. Xu He carried four sets of bricks at a time, four bricks to a set—50 kilograms in total. At the time, she weighed under 40 kilos, belly and all. With the carrying pole over her shoulder, she had to walk up an elevated plank to get onto the boat. When it rained, the plank would get slippery and flip over, and she had to lug that pesky belly of hers up the ramp, risking disaster with every step.

Every day at dawn, the entire ward of patients would get up and go to work. At the end of the day, they would come back and eat together. All of the female patients ate in the same canteen, a clay pot for each person, all in a row. Xu He would cradle her dish, often unable to keep from crying. She had hot food for every meal now, but what about her mother and younger siblings? She had been away for so long, and didn’t know when she might see them again.

For the young Xu He, as long as there was food to eat, she could endure any kind of toil. When the work points were totaled, her fellow patients would reward themselves with a few tasty dishes. For her part, Xu He would only buy the cheapest black bean sauce to mix with her rice. She was loathe to spend the money she earned, saving every cent for the day when she could leave the hospital and bring her savings home. Even though she had been separated from her family for over a decade, she still held out a shred of hope that they might someday be reunited.

—

It was on this little island that Xu He experienced her first meaningful friendships. Aside from working together every day, the patients learned to read together, chatted and joked together. New faces also started showing up at the hospital.

One day, about two years after entering the hospital, Xu He came back to the ward after finishing work and saw a very small girl sitting on the bed. Surprised, she asked why such a small girl would be there. Her wardmates replied that she was new. Xu He asked the girl, “Do you want any water? I’ll get you some.” But the girl didn’t react. The wardmates explained that the girl couldn’t speak or hear. So Xu He made a gesture for drinking. The girl nodded, so Xu He poured water in a clay bowl and gave it to her. The girl took the bowl and drank, then nodded several more times to express her gratitude.

Xu He had always liked children, and felt fond of the girl. She heard others saying that the girl had been abandoned by her family after she got leprosy, and it was the government that had picked her up. Because she couldn’t speak, everyone called her Ahnü, or “Mute Girl.” She looked to be only 4 or 5 years old, not even tall enough to climb onto the bed. Xu He thought it was a pity that such a young girl had nobody to look after her, she got a little step stool for the girl to use. Every day after work, Xu He would bring the girl food from the canteen. When she helped the girl bathe, she would make sure to scrub the leprosy spots well. The other patients joked that Xu He had taken in an adoptive daughter.

The hospital provided a fixed allowance to the patients who couldn’t work, a few yuan a month for food expenses. Xu He got another patient who used to be a teacher to help with the accounting: she recorded every cent of her food and living expenditures and kept track of how much was remaining. Even though she was helping the girl out of her own goodwill, she had to make sure others didn’t think she was after her share of money.

Toward the end of the year, Xu He saw how much money there was left on the ledger. She thought, it’s almost the New Year, and the children outside all get new clothes—why don’t I make Ahnü a new skirt? She gestured to the girl and put her hands around her waist: “I’m making you a new skirt!” On New Year’s Eve, she dressed the girl in a red skirt she sewed herself, and put her hair up in two pigtails topped off with bows. The patients were passing around fish and meat; Ahnü flitted through the crowds in her new skirt, like a butterfly flying through the fields for the first time. Although she couldn’t speak, she was smiling more brightly than Xu He had ever seen before. This joyful scene has stayed with Xu He her whole life.

—

Ahnü’s presence added tenderness and cheer to the monotonous days of laboring at the hospital. As the grass grew, birds fledged, and the seasons turned, Xu He watched the girl grow from barely the height of the bed into a young lady.

One day, the patients were sitting around, idly chatting, when someone suggested that Xu He feign sickness to see what Ahnü would do. Xu He thought it was funny, so she went along with it. When it was time for the afternoon shift, Xu He didn’t go out with the rest. Seeing her lying on the bed, the girl came over and nudged her. Xu He gestured for her to let leave her there, that she wasn’t going to work. The girl signed, “Where does it hurt?” Xu He pointed to her head, meaning that she was dizzy.

There was a kind of plant that grew along the island’s shore, shuiyonghua. It had a sour flavor, and Xu He and the others used it to brew herbal tea. The clever girl immediately ran to pick some of the flower, brewed up a batch, and poured it into a bowl. She even used her hand to check the temperature, waiting until it was warm to bring it to Xu He. At this, the other patients, who had been surreptitiously watching, laughed and exclaimed: “How endearing! She even knows to brew tea for Xu He!”

Xu He liked her more and more.

But no matter how home-like it was, Xinzhou Hospital was not a real village. After Xu He had taken aminophenol for 10 years, the doctors did a slide biopsy and said that the leprosy bacteria had dropped to a level where she could be considered cured. If, after a period of observation, there was no recurrence, she was free to leave the hospital.

By then, Ahnü was already a preteen. When she learned that Xu He was leaving the hospital, the other patients teased her, “Your adoptive mother is leaving, hurry up and get your things together so you can go together.”

The girl took them at their word. The day of Xu He’s departure, she was ready with a pair of clogs and some clothing in a bundle, which she carried on her back.

Xu He didn’t understand. She asked, “Why are you carrying all that?”

The girl signed, “I’m coming with you.”

Xu He was reluctant to leave her, but she said, “You can’t come. I might not have a place to live out there. I might have to sleep on the streets. If you stay here, the government will take care of you.”

But the girl still wanted to come, and Xu He had to reject her three more times. With no way to speak, the girl could only stand there with tears streaming from her eyes.Who knows how long the girl cried after Xu He left? Or how she felt untying that bundle, getting accustomed to eating alone, to life without Xu He.

5 / 9

Xu He left Xinzhou Hospital in 1960. Her leprosy was more or less cured, and the hospital might have also needed to make room for many new patients they were taking in. After the leprosy quarantine policy took effect in 1958, Xinzhou Hospital received a large share of patients. At its peak in 1960, the hospital housed over 1,000 patients.

Xu He’s journey out of the hospital was not all smooth sailing. She had asked around her connections in Guangzhou and learned that her parents had moved away from their hometown. After being apart for 20 years, how would she find them in this sea of humanity?

One of her wardmates had been reunited with her own long-separated family by writing letters. She told Xu He she might as well write a letter home, “So long as you know of a place, you can send it there, and the person who receives it will forward it to your father.”

Xu He did in fact have an address: A shop in the countryside her mother had once mentioned. She’d held onto this piece of information ever since she left her family at age 12. In those days, lacking means of electronic communication, the little shop was like a lighthouse in the ocean. Though her family may have moved, might someone be able to pass a message to them?

Xu He had neither paper and stamps, nor the ability to write. A kind wardmate supplied the paper and took dictation from her, writing down the events of the intervening years. She wrote the address of the shop and the names of Xu He’s parents on the envelope and mailed it off.

Amazingly, the shop still existed. And even more amazingly, the shopkeeper recognized the names of Xu He’s parents. The owner gave the letter to Xu He’s sixth uncle, who then took the letter into Guangzhou and gave it to her father.

After some time, Xu He received her father’s reply. He said in the letter that he would come see her on a certain date at the riverbank by the hospital. Xu He was overjoyed. When the day came, she walked to the riverbank alone, hoping to meet him there. A middle-aged couple came walking toward her. Xu He kept walking past them, but the middle-aged man suddenly stopped and called out, “Are you Ah-He?”

Xu He replied yes.

The man asked, “Why didn’t you greet me?”

Xu He said, “I don’t even recognize you, how could I greet you?”

“I’m your father!”

It was only then that Xu He looked at the person across from her like she was waking from a dream. This was her father, someone she hadn’t seen since she was 10 years old. She’d almost forgotten how he looked, but he had recognized her from a facial mole she’d had since childhood.

“And who is this?” She asked her father.

“This is your auntie.”

When he said this, Xu He understood that he had remarried.

She took her father and stepmother back to the ward, where they sat down and shared their stories with each other. Her father said it was only after the Japanese surrendered that he was able to get back in touch with the family members in the countryside. Xu He’s sixth uncle said that among her mother and seven younger siblings, most were dead. There might have been one sister remaining, but they didn’t know her whereabouts. Later on, her father and stepmother had started a new family, raising a son together. They now lived in Guangzhou, and worked in a coal shop.

At first, Xu He worried that her stepmother would be afraid of her. She didn’t expect that the other woman would take up her hand without any hesitation, saying, “I’m not afraid, I know it’s not contagious.”

“She’s not afraid of me.” As soon as their hands touched, Xu He’s first reaction was a rush of astonishment, followed by relief.

Reuniting with her family after 20 years apart was like being in a happy dream. After Xu He’s father learned that she was leaving the hospital, he also rejoiced, telling her to come home. After they were done talking, Xu He reluctantly walked them to the boat and saw them off.

It was a day of immense grief and joy for Xu He. She was overjoyed to see her father, but she began to feel sad as soon as she had seen him off again.

—

Before leaving the hospital, Xu He had another major problem to deal with: her belly. People had asked her about it before, and she would joke that it was just her stomach fat. When the government first took over Xinzhou, the doctors gave her an x-ray and found that there was a shadow in her abdomen. It was only then that Xu He mentioned that she had once been pregnant. The doctor knew there was no way the fetus could still be alive, and said that she ought to have it surgically removed. Xu He was terrified. She had never heard of people’s stomachs being cut open like that; she had also seen a fellow patient die of surgical complications. No matter what the doctor said, she refused to agree to the procedure.

Before she was discharged, the doctor entreated her once more to consider the surgery, listing our the benefits: “It’s free to get it done here, but it’ll cost you on the outside. And you’re still so young—if you find someone to marry? You might want to have another baby.”

Her wardmates also urged her to go through with it. Xu He pondered for a while, and, finally readied herself, like a warrior going into battle: “It doesn’t matter; if I die, I die!”

The surgery was scheduled for a Saturday. Her father and stepmother took a boat back to the hospital to sign the consent forms. She laid down on the operating table, got her dose of general anesthesia, and was out like a light. When she came to, she was amazed to see that her belly was flat now.

After a week, the wound was more or less closed and the stitches removed. A nurse took Xu He to see what had been removed. The fetus may have lived only a few months, and then remained in its mother’s body for over ten years. It was now little more than rows of bones and a skull-like form. The remains were in a glass bottle. Xu He was astonished.

The operation left a scar on her abdomen. Xu He was glad to be relieved of this burden. She had a much easier time walking. Thinking back to all those years, she felt some regret: If she had known, she would’ve gotten the surgery done earlier.

Everyone said that you had to eat well to heal after an operation, so Xu He got to eat eggs. She was very pleased with this. She only needed to eat six eggs to feel better—she could consider herself a warrior.

—

The day of her departure, Xu He said her goodbyes to the doctor, Ahnü, and her friends on the ward. She took her things onto a boat to Guangzhou, then got a ride to Huangsha Station, where she found a rickshaw to take her to Xiaobei. The address her father gave her was right by the road. This was to be her new home.

She wasn’t yet 33, with a thick head of black hair. After washing her hair carefully with tea seed powder and coiling it up in a bun, she looked quite nice. And she was a good worker—like the doctor said, maybe she really would find someone to marry.

For a time, it seemed like a new path had opened up for Xu He, one where she could be with family and end her wandering—no longer an orphan alone in the world.

But none of this came to pass. Fate had the last laugh. A power beyond human will intervened, making sure her dreams would stay unfulfilled.