Online classes and closed campuses: What was life like for Chinese university students during the past three years?

Ji Yunfei has not left his university campus for four months. For the first two he washed himself with a basin of water, as students were confined to their dorm rooms for fear of cross-infections; an experience he describes over WeChat to TWOC stoically as “self-sacrifice for [society’s] greater happiness.”

In response to an outbreak in the surrounding city of Changchun early this March, Jilin University, where Ji has been studying for his Master’s degree since late 2019, ramped up Covid restrictions that had been present since January 2020. Elevators were disconnected, classes put online, and students were told not to leave their dormitory floor. Each day, they filled out a form declaring their temperature and took a self-administered covid test, but were also woken up at 8:30 each morning by medical staff to do another test.

Ji was relatively lucky—the four years of his bachelor’s degree were Covid-free, filled with travel and dining out with friends. But for those who entered university for the first time at the end of 2019, the experiences of online learning, intermittently closed campuses, and routine health checks have been constant inconveniences during a period that traditionally offered young people their first taste of adult freedoms.

Given the constant disruption and restrictions to their university experience, “I think [students who entered after 2019] are really in a bad mood right now,” says Qian Dashu, a 23-year-old postgraduate student who wishes to use a pseudonym, pursuing a master’s degree at a major university in Beijing he doesn’t want to name (as his teachers has told him he needed the university’s permission to participate in interviews).

When the pandemic first broke out in early 2020, most students from Ji’s university had already returned to their hometown for the Lunar New Year holiday, and were not allowed to return to the university until September of that year. Initially, organizing classes online was chaos. At that time, China’s online meeting software was not well developed, so universities used platforms like Zoom. “Many older teachers were not skilled in operating computers,” recalls Ji, and were unable to read the platforms’ English instructions.

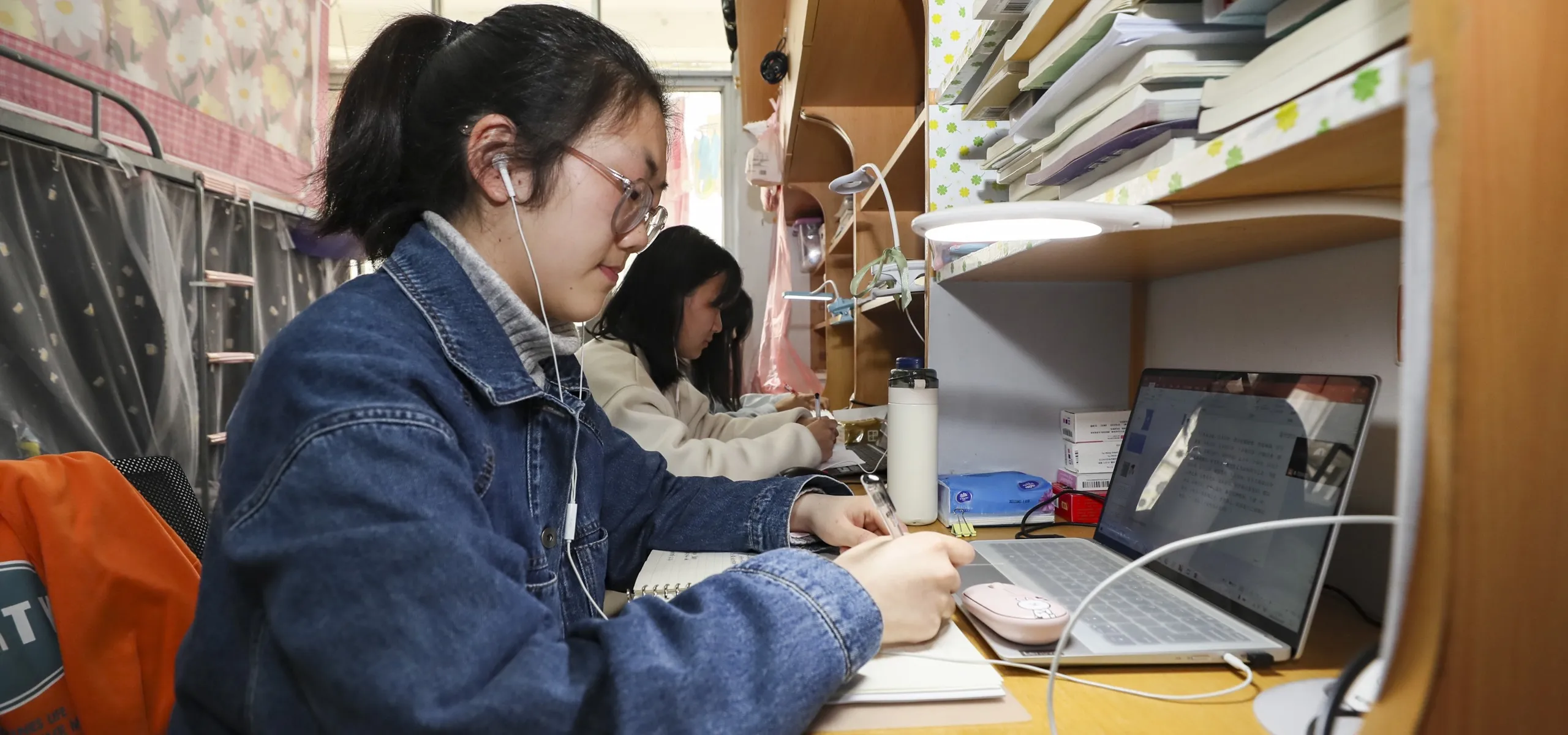

Since then, though, students have gotten used to spending extended amounts of time doing classes online, even for exams. Qian took all of his exams this year at home. He and his classmates had to place a camera on their laptops and another camera behind them so teachers could supervise them.

Others have been able to take exams offline, but that came with inconveniences of its own. “I was screaming to get in,” says Ernesto Hunziker, a student who has just finished his second year of a bachelor’s degree in international relations at Peking University, who had to retake a course last year because he was barred from entering the examination hall for his finals. The entry rules had changed only a day before, requiring students to fill out a temperature declaration form a day in advance of their exam. Teachers told Hunziker over WeChat that there was nothing they could do.

While rules were relatively relaxed in 2021, recent outbreaks in 2022 have seen them tightened again. In early April, students in one dormitory in Shanghai’s Tongji University complained on Weibo that they had to book in advance to use the bathroom, and even indicate what their “business” was, to ensure that no more than one student used the bathroom at a time. In March, Ludong University in Shandong province expelled one postgraduate student for demonstrating with a sign protesting rules that banned students from leaving campus (while faculty and staff were free to come and go).

For some, the pressures of extended confinement and getting good grades have been taxing. Qian claimed to have had anxiety attacks in his bedroom, due to the stress from taking courses online and four days of lockdown in his own compound. The university administration tried to alleviate student’s mental health challenges with a compulsory psychological test and frequent reminders that they could get a free appointment with a campus therapist. Qian chose not to book the appointment out of privacy concerns, and, as private therapy proved too expensive, he found solace in talking to friends and family.

Still, some students tried to recreate the college experience with the resources they had. Confined to his room, Ji kept himself occupied with video games, practiced his photography, and occasionally played board games with the students next door. His roommate rested regularly in a hammock he’d strung in between the beds. “Maybe it helped him relax,” Ji muses. When the case numbers began to go down, groups of students were let out to stretch in the fresh air. Ji also found some on-campus internship opportunities, like revising research papers from teachers in other disciplines.

When outbreaks were less severe, rules could be relaxed in practice, even if they didn’t change on paper. “For most of the students in our university, we share a sense that it’s OK to break the rules a little,” says Qian. To avoid being locked down on campus, Qian has been renting a small one-bedroom apartment in Beijing to take his online classes. This means he isn’t able to return to campus, but he admits to using a friend’s student card to sneak in and play games of volleyball.

Many universities have issued warnings about students neglecting epidemic prevention rules, with punishments ranging from a scolding from their teachers to an official “demerit,” which could impact their future employment opportunities. One graduate student from Shanghai was reprimanded by his university in November 2021 for writing a computer script that automatically filled in his daily health information, and sharing the script for others to use.

But the students TWOC have spoken to all say the bark was worse than the bite. For Hunziker, who had to fill in a form declaring his destination every time he left campus, a late form meant he would be put on a “blacklist” for a week, requiring him to ask for permission to go to class every day. But it’s not crippling, just an “inconvenience,” he says. Qian also notes light punishments, like a poster on a public notice board on campus calling out a student who had sneaked out to visit family in Sichuan province. “But it’s not written in your personal file,” he says, meaning future employers won’t see it.

Rules, or students’ observances of them, have ebbed and flowed with local case numbers. “It’s pretty much normal,” Hunziker told TWOC on April 22 of this year. He was allowed to leave campus, visit malls with friends, have offline classes, and play contact sports in the campus stadium. “They don’t wear masks in there and they make pretty close contact with each other.” Ji says 2021 was a normal year at Jilin University, as people “theoretically” had to upload a daily temperature report, but few did.

Changchun began to lift its latest lockdown on April 28, but Jilin University students remain on campus. “The authorities said we couldn’t open immediately,” says Ji. “Maybe things would get out of control.” On June 19, three days before the campus was scheduled to reopen, a single case discovered in nearby Jilin city delayed that again—and led to new rules banning students from leaving Changchun city, forcing Ji and his classmates to put their summer travel plans on hold.

In these situations, any little relief can be empowering. When asked what was the naughtiest thing he did during the past three years, Ji recounts, giggling, the “fun” of scrumping apricots with friends from a campus tree in July 2020. They had returned to school early, before the start of the new semester. “We had been locked in our homes for almost half a year,” he remembers. “We were just restless and wanted something to do.”