The Toutiao Missing Persons Search is harnessing the power of short videos to reunite women abducted from minority ethnic groups with their families

As of 2020, there were around 1 million missing persons cases in China, according to a white paper published by the Toutiao Missing Persons Search project. Though estimates are hard to come by, many of these missing people are women from minority ethnic groups, who were trafficked from impoverished southwestern regions of China to cities and villages on the eastern seaboard. In 2010, Chen Yeqiang, then a PhD candidate at Yunnan University, found during field research in the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture that 1,750 of 4,000 women who had left one village in the last 20 years had been victims of human trafficking.

Language barriers, exacerbated by these victims’ lack of education and by poor communication links between their home communities and the outside world, makes reuniting these women with their families a formidable task. The internet, however, has given rise to new possibilities: In 2020, China was touched by the story of Dezliangz, a woman from the Bouyei ethnic group who lived 35 years in the central Henan province—where she gave birth to two children, but was unable to speak the language of her neighbors and was know to them only as “Hey!”—before a group of Bouyei livestreamers in Guizhou province finally helped her return home.

In this episode, Story FM collaborated with the Toutiao Missing Persons Search to bring you the story of Huang Defeng, a short-video host who was one of driving forces behind Dezliangz’s homecoming; and Lu Jiaying, a young woman whose Bouyei grandmother recently found her family with help from Huang and others.

Lu Jiaying: My name is Lu Jiaying, but you can call me Ying Mei. I’m from Yangchun, Guangdong province. I was abandoned by my parents at birth, supposedly in front of a hospital. My adoptive grandfather saw someone pick me up in a cardboard box, and that person asked him if he wanted to take me in.

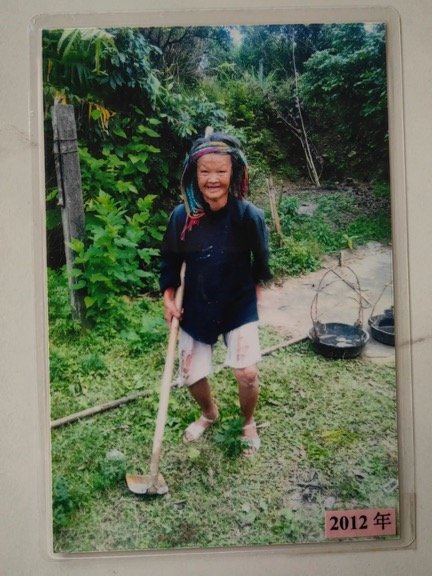

In 1995, Lu was adopted by a man in his 60s, who raised her as his granddaughter. When he died four years later, Lu and her adoptive grandmother, Ah Mei (Huang Rongmei), had to make do on their own. Life was hard without a primary breadwinner in the house. As she grew older, Lu realized there was something funny about her grandmother. She couldn’t speak the local language, couldn’t read or write, and nobody could understand what she said. Nor did anyone know her name. She didn’t even have a residence permit. People in the village said that she had been bought by Lu’s grandfather for 1,000 yuan.

Everyone in the village called her hanpo (憨婆), meaning “stupid granny.” Because she didn’t speak the local language, they thought she was slow or mentally ill, and would make fun of us. They’d say things to me like, “Simple granny is raising a simple little girl!”

Maybe I felt some resentment, because I didn’t like to spend time with my grandmother. Sometimes, if I saw her when I was out with my classmates, I didn’t want to acknowledge her.

When she was 11, Lu was adopted by another family. Her adoptive parents were very good to her, and frequently took care of her grandmother as well. This kindhearted family began trying to find out more about Granny Ah Mei’s past, but due to the language barrier, they didn’t make any progress for over a decade. In 2016, Lu’s grandmother had a bout of illness that required amputation of her right leg above the knee. Shortly afterward, she developed cataracts and a goiter. Lu’s foster family decided that they couldn’t wait any longer. If they wanted to help her grandmother find her roots and return home, they would have to harness the power of the internet.

Lu joined many online groups, sending recordings of her grandmother’s speech to different people for identification. She hoped that somebody would be able to recognize her grandmother’s dialect.

I recorded every day. Whenever she spoke, I would send the recording to the groups to see if anyone could place the dialect. During that time, everybody did their best. They would ask how she pronounced the words for “chili pepper” and “chestnut,” because they said they could determine the region based on that.

Huang Defeng is a user on Douyin, China’s TikTok, who broadcasts under the handle “Feng Xiaoxiao.” He belongs to the Bouyei ethnic group, and works as a civil servant in his native Guizhou province.

You may have heard of Huang because in 2020, he helped a Bouyei woman named Dezliangz find her family. After being trafficked as a young woman and living without a name for 35 years, Dezliangz was finally able to reunite with her parents. Two years later, Huang Defeng once again played a crucial role in Lu’s search for her grandmother’s family.

Huang Defeng: I listened to the recordings [that Lu uploaded] over and over again. The more I listened, the stronger my conviction grew; it was very similar to my people’s language. Granny was saying, “It’s raining very hard and the wind keeps blowing.”

I said, you can hear it clearly, this is our language. It’s got to be Bouyei or Zhuang language, because we speak the same language—it’s similar to the difference between the Beijing and Northeastern dialects. I knew right then and there that I would help this grandmother find her family.

Ying Mei later said that she had initially reached out to me on Douyin, but I never responded to her message. So she found another Bouyei woman called Hani, who has also been promoting the Bouyei language, clothing, and culture on Douyin. Hani listened to the recording, but couldn’t understand it. So she said, “I have a friend who has more experience with this, who has helped abducted Bouyei people find their relatives before. I can forward your message to him.” And what do you know, she found me again.

I started by sending the recordings of Granny Ah Mei to various Bouyei chat groups, but nobody could understand them. They said this wasn’t our language, that it was more like the Miao or Yao language. But I felt that it had to be Bouyei, because I heard that sentence so clearly in the middle. She said, “It’s raining very hard.”

Later, some of our Zhuang friends said that they could also hear it, that Granny really is speaking our language—especially our brothers and sisters in Longlin, who said they could understand a significant amount. A sister named Luo Su, who is a Zhuang folk singer from Longlin, said that she could understand Granny especially well.

We set up a group called “Help a Guangdong Yanai Return Home”; yanai is a Bouyei word meaning grandmother. Of course, it wasn’t easy. I was exhausted during that period—I would work overtime until 10 or 11 at night, and then the first thing I’d do after I got home was to take out my phone and look through the group chats, reading everyone’s analysis of the recordings.

After four or five days, there was still no news yet. So I put out a video on Douyin to try to find her family. I figured that even a slim hope was better than nothing.

Six days later, I received good news. It was unexpected, because the video didn’t get many “likes.” But there was a relative newcomer to our group, a man named Wei Xueying, who kept insisting that this grandmother’s accent had to be from Longlin county.

There’s a place in Longlin called Bianya Township. He kept forwarding the recordings to WeChat groups based in the area, and later someone from Granny’s family saw my video and reached out to me through the contact information I left.

The man who contacted me—I call him Uncle—was Ah Mei’s nephew. He added me on WeChat and said, “The old woman in the video you sent is my relative.”I was so excited when I saw that message. I was exhausted that morning after working overtime the night before; I could barely keep my eyes open. But when I saw those words, my eyes lit up.

I immediately checked to see if his WeChat profile had his phone number on it. When I saw that it did, I called him and said, “Hello, I’m Feng Xiaoxiao. I saw your message.” He was overjoyed, saying, “Yes, yes, she’s my relative.”

He said, “You can stop looking, I’m 100 percent sure that this is my aunt.” I asked, “How are you so sure?”

He replied, “First of all, I still remember what she looks like.” He remembered when his aunt was abducted, saying that as soon as he saw the photo, he knew it was her. And her accent hadn’t changed—he said that she more or less spoke like this when she was young. She also had a bump on her neck, which grew into the goiter; everything lined up.

I was so happy it felt like I’d won 10 million yuan in the lottery. Though I’ve never won the lottery, I feel that even if I did, I couldn’t be any happier than I was at that moment.

It was incredibly difficult to help Granny Ah Mei find her family. She had very poor hearing, and even when she later got hearing aids, she couldn’t make out what we were saying. Many of our compatriots in the group—we called ourselves bixnuangx, the Bouyei word for “brothers and sisters”—would take turns talking to her through video calls and voice chats. We tried every method available to us, but Granny either couldn’t hear us, or couldn’t make out what we were saying.

We were on the verge of giving up. There are over 20 million people belonging to the Bouyei and Zhuang ethnicities, and it was hard to find her relatives in such an enormous group of people. Even though we are called ethnic “minorities,” there are still a lot of us.

In May of 2022, Huang became a volunteer for the Douyin Missing Persons Search, which is part of a program called the Toutiao Missing Persons Search. The program is active on both news portal Toutiao and on Douyin. These platforms direct internet traffic toward content about missing family members. Huang has also encouraged his friends to join as volunteers.

In the beginning, Huang had only wanted to use short videos to share things from his daily life. He was born in 1990, and comes from Anlong county in Guizhou’s Qianxinan Bouyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture. There are around 3.5 million Bouyei people in China, most of whom live in southern Guizhou. Across the river from his hometown is Guangxi's Longlin county, home to the Zhuang people. The two ethnic groups share linguistic origins and have similar customs.

My name is half Bouyei, half Han. My Bouyei name is Dezfeng. Dez is a prefix in the Bouyei language, similar to Xiao Feng or Ah Feng. It’s the same as the dez in Dezliangz.

I spent my childhood in the city now known as Panzhou in Guizhou. I lived there until I was 10, when I returned to the countryside. Because my parents were both from that area, and so was my grandfather, I grew up speaking Bouyei.

When I moved back to the countryside, I started learning the Bouyei language and having Bouyei classes each week. I thought these classes were a lot of fun.

Back then, everyone in my class could speak Bouyei. We used Chinese in school, but spoke Bouyei the rest of the time. I always thought there were no Han students in my class—until the sixth grade, when we took our junior high entrance exam. There were bonus points offered for certain ethnic groups, so the teacher asked the class which of us were Bouyei and which were Han. At the time I was confused: Did we even have any Han students?

The teacher asked the Han students to raise their hands, and there were about 10 students who did so. I thought this was very strange, and asked them, “How could that be possible? You all speak Bouyei, how could you be Han?” Later, I looked at their household registers and saw that they really were Han.

This was incredible to me. Our ethnic languages were thriving back then, completely different from how things are today.

I went to high school in the main town of our county. Half the class was Han, unlike my previous school, which was 90 percent Bouyei.

My class had 50 or 60 students. There were about 20 or 30 Bouyei students, but only three of us could speak Bouyei—just one girl and one boy aside from myself. I felt a sense of cultural crisis, because language is such a precious part of our cultural heritage.

In order to protect the Bouyei culture, Huang started posting videos about the culture on Douyin.

When I was starting out, I would post videos about my life and get only a few likes a week. Sometimes I didn’t even get any likes. Other times I’d see a bunch of likes when I opened the app. I’d get excited, thinking that I was about to go viral, but then I’d see that they were all from my mother. I didn’t think to use Douyin to promote the Bouyei culture until I stumbled into it.

There was a period when “neck-bobbing videos” were very popular. People all over the country were posting clips of themselves bobbing their necks from left to right. In the comments, I saw people saying that our Uyghur brothers and sisters have incredibly flexible necks.

I responded in that thread, “Same for us Bouyei, even Bouyei men can bob their necks.” They said, “Really? Show us.” So I posted a video on Douyin, my first-ever video linked to my heritage. I said, “I am a member of the Bouyei ethnicity in Guizhou, we also know how to bob our necks.” To my surprise, I got several thousand likes, including a comment asking if I was Bouyei. I said yes, so the user asked if I could speak the language. He said, “If so, can you post some instructional videos? I am also Bouyei, and I would really like to learn our own language.”

I realized then that there was another way I could use Douyin. After a while, I posted a video with basic phrases in Bouyei, like “eat,” “drink,” and “are you coming?” After I uploaded this clip, I got quite a few views—the video now has almost a million views.

There were many people who started appreciating their own heritage after seeing my Bouyei culture videos. They realized that we could proudly display our culture online for all to see. In the past, many people thought that Bouyei was a backward language, that it could only exist in the vegetable markets and fields, deep in the countryside.

After Huang started posting his videos, more people became aware of the Bouyei culture and language. Those who knew Dezliangz and Ah Mei also realized for the first time that the “odd speech” of their elders was actually an ethnic language. Huang and some of his Zhuang and Bouyei friends made an online group called “Bixnuangx, Come Home.” The group remained active after Dezliangz was reunited with her family. Whenever a new search was initiated, group members would respond, doing what they could to help their brothers and sisters find a way home.

So far, in addition to Lu’s grandmother, Ah Mei, the group has helped six strangers locate their families.

The first one was Dezliangz, the second was Luo Xiaocai, the third was Chen Guimei. Chen Guimei was a girl from Guangdong who wanted me to help her find her mother and younger sister.

The fourth was Wu Wenhua. There was also a Zhuang woman from Wenshan, Yunnan province, who’d been abducted to Shandong, whose name in the Zhuang language is “Ni.” She is the second-oldest in her family, and ni means “second.” After she was abducted, her son sought help online.

The day after I posted the video on Douyin, there was good news. A kindhearted man from Funing, Yunnan, messaged me to say the woman in the video had gone missing from a family in his area. I was thrilled.

Quite a few people have sought me out to help them find their missing relatives; maybe one every two or three days. During busy periods, I get a message a day from Bouyei, Zhuang, and Han families, because Dezliangz’s story made a big impact. I never thought that I would reach so many people from around the country. If somebody finds me, no matter what ethnicity they are, I do my best to help them.

I like reunions, because first of all, the Bouyei people love reunions. When a holiday comes around, we can’t wait for the whole family to get together. When we celebrate the Liuyueliu Festival [a Bouyei festival named for the sixth day of the sixth month in the lunar calendar], the whole village gathers to make sticky rice cakes and participate in the leiwu ritual together. Lei means “to run”, and wu means “to cheer.” So we run, and we cheer, and we dance around a bonfire. This is the kind of atmosphere of togetherness that we enjoy.

Also, ever since I was little, my parents have worked outside the home. My mother was out doing business every day, working long hours, while my father was a coal miner. I wasn’t able to spend much time with my parents when I was young, so I have a kind of longing for family reunions. So now, when people ask me to help them find their relatives, I understand what it feels like to want to reunite.

I want to see people come together, whether it’s in my life or the lives of others.

But every search is a challenge; I never expect everything to go smoothly. Many people ask me for help, yet many of them haven’t heard anything back. Sometimes this depresses me as well.

For example, I helped a family look for their two missing sons, young brothers who had been abducted at the same time. When I visited their home, the father was already in his 50s, but he had kept his children’s clothes all these years, and their school books and supplies. He was a big strong man, but when we started talking about his children, he wept openly. It was hard to watch. What kind of tragedy could make such a middle-aged man cry in front of the camera?

The clothes in those two kids’ suitcases were neatly folded, and their books and stationery were still like new. It really hit me hard.

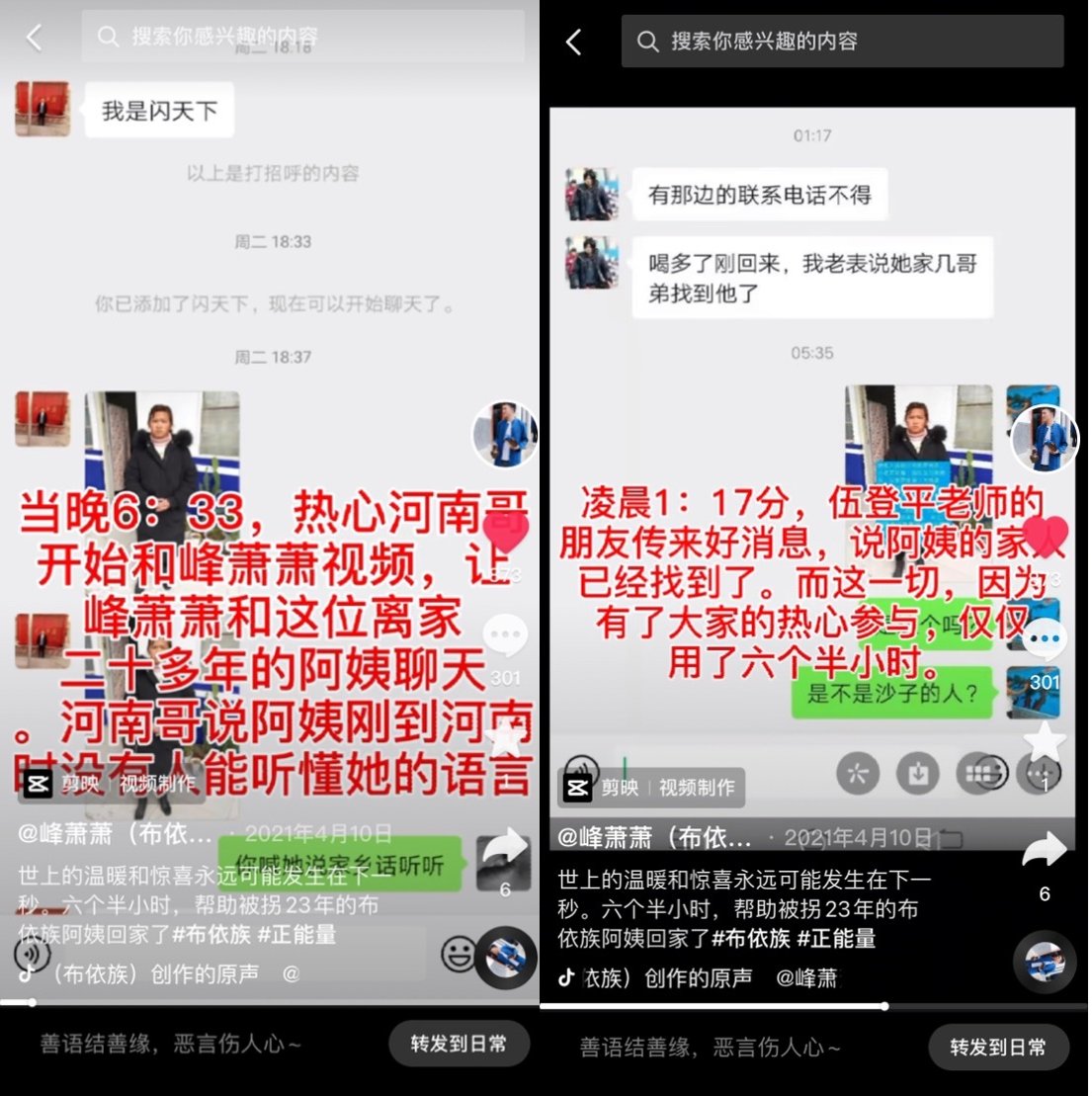

It’s not easy to find a needle in a haystack, but Huang has never given up, because he knows he’s using the right methods. Back in April of 2021, a Bouyei abductee named Luo Xiaocai was able to return from Shangqiu, Henan, to her hometown in Guizhou. The whole process, from the moment Huang received the request for help to when he made contact with her relatives, took only six hours.

There is a man I call my Henan Brother, and he has a big heart. He said, “I saw on the news that you helped Dezliangz reunite with her family. My neighbor is also a woman who was abducted to this place 20 years ago, and has wanted to return home this whole time.” He asked, “Would you be able to help her find her family?”

I said I could, so we talked on WeChat. I asked if he could get her on the phone, so he went to find her—Luo Xiaocai. At the time, I didn’t know that she was called Luo Xiaocai, because she had given me another name. I later spoke with her on the phone, and she told me her name. She also remembered her brother’s name and her father’s name, but she said it in the Guizhou dialect, which the Henan locals couldn’t understand. I only got the gist of what she was saying, because she had picked up some of the Henan accent as well. I asked, “Where are you from?”

She said, “I’m from Zhenning County,” saying “Zhenning” in a Henan accent, but she looked Bouyei in appearance. I said there was a high chance that she is from the Bouyei people in Zhenning county, because the full name of the county is “Zhenning Bouyei and Miao Autonomous County.” I compiled the photos and information she gave me into a video, which I sent to a friend in Zhenning. This friend, Wu Dengping, teaches both Chinese and Bouyei language there. He forwarded my video and mobilized people there. Everyone helped out, and six hours later they found the woman’s relatives. She was the daughter of a local family named Luo. Her father was still alive, but her mother had passed away.

Huang knows that there’s never a guarantee of success, so he’s always hoping to reach and engage more people. In the past two years, he has posted information about many searches on his Douyin page, including for Luo Chaofan, Qin Shicai, Xiao Mingbo, Xiao Minglang, Xu Xiaohua, Liang Guangmin, Cen Huicheng, and Xu Xinzhong. Behind each of these names is a person who has endured many long years of separation from their family.

After Dezliangz returned home in 2020, Huang uploaded a video on Douyin of himself singing a Bouyei song called “Waiting for You.” The lyrics go: “I can’t leave you, I’ve never left you, I’ve waited for you until daybreak. No matter how many years I wait, in this life you’re the only one I’m waiting for.”

For Dezliangz, Ah Mei, and Luo Xiaocai, the key to finding their relatives was the fact that they had never forgotten their hometowns and loved ones. Local languages bring people together and help them find one another.

Since its inception in 2016, the Toutiao Missing Persons Search has helped reunite over 19,000 people with their families. Among them, the oldest was 101, while the youngest was only 3 months old. Currently, Toutiao Search is one of the largest public missing persons search programs in the country. If anyone around you needs assistance, you can lend a hand: Your likes, shares, and messages might help somebody find their long-lost home.