A second-generation village physician reflects on the decline of her profession and its uncertain future over a 20-year career

Last year, I entered my final year of medical studies. As I waited for the results of my postgraduate entrance examination, I submitting my resume left and right just in case I needed to find a job. But I heard nothing back on either front.

Forced into being idle, I called Dr. Han. Half-joking, she asked whether I would be keen on returning to take over her clinic. “Fair enough,” I smiled. “I’ll go home and take on your job if I can’t find one.”

Dr. Han balked immediately. “I was just kidding! How could I ever let you come back to this? Kid, you better work hard to stay at that big hospital and get something to fall back on, you hear me? You promise me?”

She emphasized “fall back on.”

I was perfectly aware that Dr. Han’s profession had been a thorn in her side throughout her entire life. Yet it was not a thorn she was willing to remove.

1/7

Dr. Han is a village doctor. She is also my mother.

Dr. Han has always approached her work with a mix of passion and resignation. Every morning for the last 20 years, without interruption, she’s woken up at dawn to go to work at her clinic in the nearby village. I often mocked her for her devotion to her occupation, which sounded grandiose but was actually very humble: a phoenix from afar, a chicken from close up.

Far from being offended, Dr. Han agreed with the comparison. “That’s spot-on.”

In fact, Dr. Han had indeed been a “phoenix” in a former life. When she graduated from high school, my grandmother had arranged for her to go to medical school. She finished her medical studies in 1993 and remained in town to manage the local hospital. Dr. Han worked there for two years before marrying my father, who hailed from her home village. Three children followed in close succession.

Our family home is in the village too, some 15 kilometers away from Dr. Han’s hospital. My father had long left to work in another province, leaving his wife as the sole caretaker of their children on top of holding down her own job. Dr. Han never got along with her mother-in-law, who in turn washed her hands of her grandchildren. At times, Dr. Han wanted to quit her job in town and return home, overwhelmed as she was with her daily toil.

It was right around this time that another job offer came to my mother. My grandmother had been the first rural doctor in our village, but she felt that her working days had come to an end. Therefore, she thought of Dr. Han as a prospective successor at the village’s clinic. Dr. Han had grown up witnessing the high status and prestige accorded to doctors in the countryside, so she held the job in great esteem. Furthermore, wages were rather good, and she could stay close to home to care for us kids. Long story short, Dr. Han was thrilled to follow in the footsteps of her mother.

***

In 1999, Dr. Han reported to the rural health center. In her early days as the newly minted second-generation doctor to our village, she set up her clinic in a vacant room in our family home.

These were not spacious premises. Dr. Han made the larger room outside a consultation room and pharmacy, while the inner chamber was repurposed as an injection room. She tasked my dad, who had once worked at a furniture factory, with designing and assembling a pair of medicine cabinets, two desks, and a workbench. The set was uniformly painted with light yellow paint and passed Dr. Han’s joyful inspection.

These were the foundations of Dr. Han’s budding career as a village doctor. In the morning, she cleaned the clinic before properly starting the work day. Dr. Han would wipe her desk until light reflected on the surface. The stools were all neatly placed by the wall. She said, “If a worker wants to do a good job, they must first sharpen their tools! Same with a health clinic!”

Her statement didn’t impress her family much. After all, we just saw her as a wife and mother. She was a poor homemaker. The cotton trousers she’d sewn me were lumpy and uncomfortable, and her cooking wasn’t particularly enticing either. Father often teased her at mealtimes with comments like “Why, kids, Mom’s tricking us again—she told us we were having shredded potato and now she’s bringing us potato chips!” or “Did you wipe the table or did you oil it?”

Grandma had given up teaching Dr. Han to knit sweaters, declaring her a lost cause. But when she spoke of her daughter’s prowess as a doctor, she was full of praise: “Ah, your mother is one smart woman—one glance is all it took for her to learn all about needles and infusions! She was born for this job.”

My siblings and I were not convinced at first, but when we witnessed Dr. Han’s performance at the village clinic, we never doubted her again.

***

At the time Dr. Han started her practice, it was still rather inconvenient for people to go see a doctor in the city. The village was composed of some 300 households that kept my mother plenty busy. Dr. Han took on all sorts of appointments—general medicine, obstetrics, pediatrics, and even some simple surgery. No matter what kind of problems they had, villagers all flocked to her immediately.

“Dr. Han, my baby has a fever!” “Dr. Han, my father can’t move his feet!” “Dr. Han, hurry! I sliced my hand open while cutting leeks.” With every emergency, Dr. Han would drop whatever she was doing and rush out the door. On her way out, she would warn us three kids to “guard” the house and not open the door to strangers. Given the frequency with which this occurred, Father said jokingly: “You three are so well trained, we’ve no need for dogs.”

Not only did Dr. Han tend to all these “emergencies,” she also regularly visited patients who were elderly or financially disadvantaged. Dr. Han showed nothing but empathy toward their struggles, and was always willing to find a way around medical expenses. She tried to cut costs for them wherever she could, and even covered fees out of her own pocket when they could not pay.

Whenever she was not making house calls, Dr. Han stayed at the clinic in our family home to see her daily influx of patients. Everyone in the village knew one another and were always up for a chat after their appointment with Dr. Han, who was quite the chatterbox herself. She had a great sense of humor and often managed to soften even the sternest scowl from her patients on arrival to the consulting room. All in all, she was the poster child for the saying: “Doctors sometimes heal, sometimes dispense care, and always bring comfort.”

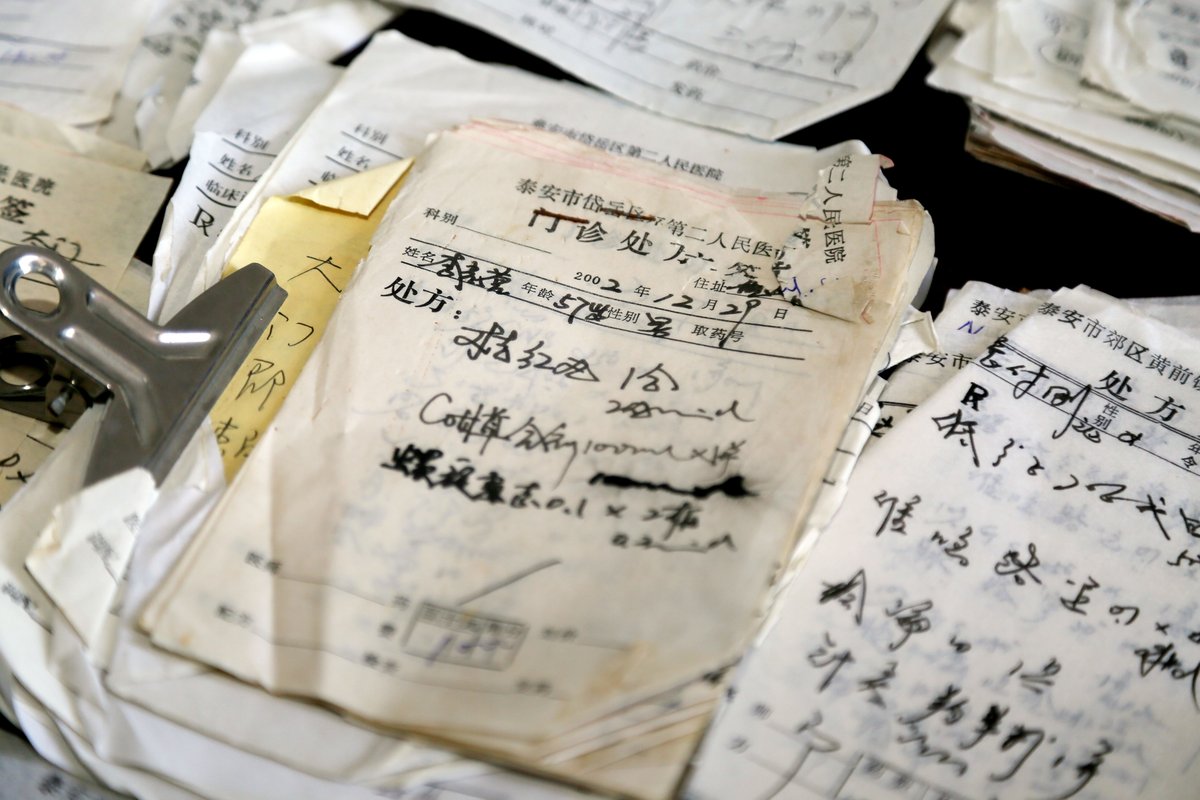

I once saw Dr. Han’s diary by accident, which gave me a glimpse of her daily experiences:

“It took several attempts to jab Old Ji today. I need to improve my technique.”

“Auntie Tang has had a nasty cold for several days. I have to try another medicine.”

“Uncle Liu is complaining of pain in his lower back and legs—I need to take him to see a Chinese medicine doctor.”

In those years, the villagers sung Dr. Han’s praises. I would be walking by with my friends and folks would greet me, “Why, it’s Dr. Han’s second girl! Where are you playing today? Is your mother at home?” Whenever I’d find myself on South Street, Auntie Pangxia never failed to greet me warmly with an invitation to pick cherries at their house. Grandpa Turtle, who ran a tobacco shop at the west end of the village, always had a wad of bubble gum for me.

Dr. Han’s job also granted our household a good income. My brother, sister, and I always wore fashionable clothes and were spoiled with the latest toys.

2/7

The new rural health insurance scheme came into being in 2003. I was a second-grader at the time, so I didn’t understand what it was. All I knew was that every household was issued a small booklet that they took with them when they went to see a doctor, and this allowed them to take their prescriptions home without paying. Some naughty kid in my class came to show off his family’s book to me: “Ha, ha! We can show this to your mom and get our medicines without paying anything!”

That day, when I came home from school, I interrogated Dr. Han with a serious face: “Why won’t you charge those people for their medicine? If you keep doing that, there won’t be any money for me to go to school!”

Faced with my concern about our family’s livelihood, Dr. Han burst out laughing: “This second daughter of mine is all grown up. Look at her urging her mother to make more money!”

The new policy also required rural doctors to keep a record of the households in each village and the number of people in each family, as well as the number of people with diabetes or high blood pressure. The doctors kept a record of the prescriptions they gave out, and got the money for it from the government at the start of the following month.

Despite how time-consuming and labor-intensive this new system was, it earned Dr. Han’s praise: “Good method indeed, formal and efficient.”

The government did not stop there. The following year saw new guidelines that formally conceded rural doctors the status of healthcare providers. Before, township doctors could simply start their practice, and villagers who trusted them went to see them. All they had to do was to register at their local health center. My grandmother had been nominated by her socialist “production unit” to attend nursing school, and was assigned to practice medicine in her home village after graduation. Most of the rural doctors of her generation had a similar story.

Things were set to be different now. Under the new regulations, Dr. Han had almost daily meetings at the town health center, which served as a headquarters of sorts for all rural doctors in our area. Still, Dr. Han was relentless in her optimism: “All I need to do is pass this test to get my business license under the new guidelines. Then, I’ll be a full-fledged member of the national healthcare system.”

“I see. Can you really pass the test?” I asked. As an elementary school student, I dreaded exams.

“Listen, kid, your mother here is a powerful woman. Failure is not a word in my vocabulary.”

Dr. Han occasionally took me with her on these meetings at the hospital. There, I got to meet the person in charge of township healthcare affairs—Dr. Guang, a man whose large eyes popped out from beneath his thick brows. After each meeting, he could be found distributing materials to a series of distressed-looking doctors, who gathered around him to ask all sorts of questions. Dr. Guang wet his index finger with a decent amount of saliva in order to flip through the block of paperwork that he handed out to the crowd. However, he wasn’t very articulate, so he relied on Dr. Han to translate the professional jargon in these papers to everyone in more approachable terms.

Dr. Han succeeded every time—after all, she was a college graduate, which meant that she was the most educated among her peers. Her lively, engaging explanations were a blessing for her fellow doctors, who nodded approvingly: “You can certainly tell she’s educated.” My mother beamed at the praise.

The final exam came in September 2006. Some of the rural doctors failed and were therefore banned from practicing. Dr. Han passed with flying colors and was subsequently issued with her license. Her success only strengthened her already ambitious expectations for the bright future of rural doctors.

3/7

In 2008, I graduated from elementary school and went on to junior high school. When my next holiday came, I returned home and accompanied Dr. Han to the hospital for one of her meetings, just as I had done in the past.

However, this time around, her face was no longer so bright. Soon enough, I found the reason for her gloominess. In order to better serve the people and further reform the healthcare system, the government had decided to carry out price reforms on prescription medicines. Medications were to be sold without any markup. Such were the instructions that Dr. Guang conveyed to all the township’s rural doctors, straight from the higher-ups.

The crowd was not impressed. Huddling around Dr. Guang, they clamored: “So what about our own earnings? There’s no profit margin with that policy. We’ve got families to feed!”

Dr. Guang was helpless: “I’m just a messenger. What’s the point in yelling at me?”

The crowd disbanded, grumbling. Rural doctors are on call 24 hours a day, and are bound to their profession and their geographic location by their sense of duty. Before, they could make some extra income from the markup on selling prescriptions, but that option was now gone. (Editor’s note: the price of prescription medicine had always been regulated. However, this policy wasn’t well-enforced before, and doctors would set their own prices, though most stayed within reasonable limits.)

On the way back home, Dr. Han was still sullen. She confided to me: “Actually, it’s a good policy. Many of our elderly and widowed neighbors will finally be able to afford their prescriptions. However, it’s still unfair to us doctors. You know Uncle Jia from the next village? He’s looking for someone to take over his clinic. He’s not willing to put up with this.”

Dr. Han herself was now a middle-aged woman, with parents to support as well as children to raise. Even with her lofty ideals and aspirations, life seemed to be hinting to her that it was time to move on. Indeed, many other rural doctors left the profession after this, but perhaps because her children were still young, or for some other reason, Dr. Han persevered.

Back then, Dr. Han kept her graduation yearbook on her desk. The first page featured a message in her own handwriting: Faced with a patient seeking help, do not inquire whether they are rich or poor. All patients should stand on equal terms in your heart. As a doctor, you should regard your patients’ well-being as that of your own kin, and their pain as your own. Always have kindness in your heart.

The government did spare some thought for the livelihoods of rural doctors. It would reimburse the cost of medicines to these village doctors, and they also received a so-called “visit subsidy” of some two or three yuan per patient they saw.

Even so, Dr. Han’s income was effectively halved by the new policy. At the end of every month, Dr. Han reported back from the health center and gave a pained look at the numbers on her small ledger: “I want all these villagers to have a doctor covering their needs, but I still need to make a living.”

My father made a decent salary. However, family expenses had only soared as my siblings and I grew up. The dwindling of Dr. Han’s salary lowered our family’s living standards by a sizable margin. The quality our meals and clothing declined accordingly.

4/7

Little did we know that even before the dust settled on this new policy, we would soon be facing yet another storm. The government now required all rural doctors’ clinics to be located independently from their family home.

The news was followed by an instant uproar. Dr. Han got many a call from colleagues, all voicing similar complaints:

“How am I supposed to locate the funds to build a separate clinic? As if I can even afford my children’s school fees these days!”

“I’m done with this. I’ll just go out to find another job. Do you know the cost of living in our town…?”

Changing lodgings was not just expensive—it also involved plenty of time and work. Most rural doctors still tended to their family’s fields in their spare time. Moreover, having a separate clinic meant they would no longer be able to juggle family affairs with their working hours. Rural doctors were effectively left to figure out a solution themselves.

Once again, a crowd of incensed doctors took with their collective concerns to the health center. The ever-present Dr. Guang took note of everyone’s opinions and promised to convey them all to the higher-ups. However, all efforts proved futile. Workers could not possibly get the government to budge on a policy that had already been implemented. The government promised to subsidize these health care professionals. However, when everything was said and done, very little went to the hands of rural doctors. Funds for these subsidies had been skimmed off at each level of government, and whatever meager amount was left to the doctors was nowhere near enough to build a second house.

The higher-ups tried to appease everyone with a promise to set rural doctors up who met certain standards with supplies and equipment, such as beds, computers, and infrared lamps. The rest had to wait for more funding.

Dr. Wang, from a neighboring village, had originally been the loudest detractor of the new policy, vowing to “never compromise, never build a separate clinic.” Dr. Han followed in her steps and voiced her discontentment just as loudly, only for Dr. Wang to back down. The minute she saw some of her colleagues receiving equipment from the government, she cleaned out an old courtyard home belonging to her family and moved her clinic over. When the pair met at the next doctors’ meeting, she said, embarrassed: “Oh, well, it can’t be helped, everyone’s going with the policy. What can you possibly do about it?”

Dr. Han’s anger was only second to her feeling of helplessness at seeing all her peers getting the equipment from the government. She thought of her mother’s old home, which was left vacant after she moved in with our uncle upon retirement. She told my father over dinner: “Why should they be getting all this stuff while I go without? Let’s clean up Grandma’s yard and move the clinic there!”

Father waited some to swallow the soup he’d been sipping on while listening to Dr. Han. Met with her intense stare, he nodded and conceded: “Okay. I’ll go clean it up tomorrow.”

The next day, he set out to buy supplies. He worked hard from late autumn until the end of the year. I came home from school one day and found Dr. Han in the main chamber, giving directions as Dad tinkered over a brand-new computer. There were also two hospital beds in the room.

Dr. Han cackled: “We just need some more chairs. Let your dad go fetch some tomorrow and everything will be ready!”

I looked back at Dad and he simply shrugged back at me: “She was just jealous of the other doctors’ stuff.”

***

It soon became clear that any alleged gift from the government would come with strings attached. Equipped with their new computers, all township doctors were now required to learn how to operate them, starting from inputting the villagers’ basic information, their medical records, and other data pertaining to the new insurance system into the system. Now, these rural doctors were over 60 years old on average. Most of them had never touched a computer before. Even Dr. Han, at 38, was not exempt from the headaches that followed.

The sight of my mother slumping in front of a computer, struggling to learn how to type, was such that I had to tease her: “I wonder, will you be able to learn it?”

My gentle mockery did not go well with her this time. Dr. Han slapped me: “Why can’t I learn? You damn brat. I’m not some old lady in her 80s, you hear me? I’m no fool. A mere computer is no match for me, so don’t you dare look down on your mother.”

Her lashing out made me reach over to rub her shoulders as I nodded in agreement: “Come on, Dr. Han! You can do it!”

5/7

The health center convened the rural doctors to take a series of courses on basic computer skills, mainly covering logging in and operating the township’s medical website. Dr. Han picked it up right away.

Our family had gone to great expense to transfer Dr. Han’s clinic to Grandma’s old house. The government’s subsidies and their equipment had barely made a dent in our budget. Fewer people lived in the village nowadays, anyway—more and more people were commuting into town to work, and the road had improved greatly. Many of our neighbors now preferred to flock to the big hospitals even for minor illnesses. Meanwhile, the municipal government was exerting more and more control over rural doctors. Dr. Han was now overwhelmed by the whirlwind of monthly reports, routine meetings, regular check-ups for the villagers, follow-up sessions, and countless other matters. Her feeling of powerlessness returned with a vengeance and her complaints about her job became more and more frequent.

In spite of her vocal discontent, she was still doing her best to serve her patients in the same way she had before. She would follow so-and-so’s young daughter-in-law to the hospital to assist her in childbirth; she stayed by the sickbed of a lonely and elderly widow with a blood pressure monitor, ready to nurse her all night; she pulled all the strings she could to ensure that critically ill patients would be transferred to the big hospital, and she would always call to inquire on their condition afterward. My sister often asked Dr. Han whether she couldn’t find any other occupation, seeing as her current one was sapping her spirits.

I felt inclined to agree, if only for one reason—I could see that some people were starting to ignore Dr. Han’s selfless work. Some villagers resented what they thought to be the government’s strong support of rural doctors through housing and equipment subsidies, and thought she must be earning a lot of money on the side. Dr. Han had always been scrupulous about the regulations, rallying elderly villagers for physical check-ups and regularly taking their blood pressure and blood sugar levels. However, when a health inspector came by for a visit, some of these old folks would pretend that things were not being done right: “Huh? Follow-ups? I don’t know anything about that!”

Their lies by omission were more than enough to overshadow Dr. Han’s hard work, and the bigwigs would target her with criticism every now and then.

The next time she visited those elderly patients, Dr. Han would ask them why they’d lied. However, they would keep playing dumb: “Oh, did measuring my blood pressure count as a follow-up? Gee, I wouldn’t have known. You see, I’m too old, my mind’s getting slow. Don’t take it to heart. Next time I’ll tell those higher-ups!”

“What can I possibly do?” Dr. Han would sigh. “Every time’s the same, I tell them and they never change their ways.”

Her heart was no longer in her work. She took to taking a short nap after lunch every now and then. Whereas she used to stay at work until almost 10 o’clock in the evening, now she’d sometimes be back home as early as 7.

On one of his visits to us, my mother’s brother tried to persuade her to give up the clinic: “What’s the point? Just go to the city and open a small clinic there. Anything’s better than this lousy village clinic.”

Dr. Han said she would give some thought to Uncle’s advice, but she’d eventually decided to stay put.

In the summer of 2010, I was in my third year of junior high school and so anxious about my studies that I had little time spare to go home. Once, Dr. Han told me over the phone that she was about to qualify as a nationally licensed assistant physician. She spouted off a bunch of what sounded like inspirational quotes, such as “the struggle to strike gold” and how “we must not fear not having a chance, but rather unpreparedness.” I was confused.

Later, my sister helped me make sense of Dr. Han’s tirade. The town health center had imparted a grandiose lesson on all rural doctors, stating that the state had spared no efforts to back their work, implementing numerous good policies for the opening of clinics all across the countryside. Doctors just had to keep their skills up-to-date. “There shall be no shortage of opportunities for promising talents displaying medical ethics and skill in the field, and generous rewards are sure to reach these good doctors!”

My verdict was merciless: “Dr. Han has been brainwashed!”

I thought her enthusiasm would be a mere flash in the pan, but I turned out to be wrong. Dr. Han unpacked all her medical books at home, found her old notes from medical school, and signed up for one of those training classes that promised a “full, unconditional refund” to students that did not pass their exams.

Attentive as Dr. Han was, she was unable to replicate the energy and zest of her youth. It took her three years to get her qualifications.

The exam was divided into two sections—practical operations and theory. The former was arranged yearly in the month of June, and only successful examinees could go on to sit the theoretical written test in September. Dr. Han failed to pass the practical portion of the exam on her first go. In the second year, she passed that one but failed the written test. She said she would give herself one last chance the following year. Over the course of her third year, she seemingly forgot to eat and sleep, burning the midnight oil for several consecutive nights as the fateful date approached. I accompanied her to the exam venue and left the examination room with a cheer: “Don’t be nervous, Mom, you can do it!”

On June 26, 2013, 42-year-old Dr. Han became the first among her cohort of local rural doctors to obtain the National Qualification Certificate for Practicing Assistant Physicians. In the years that followed her triumph, she strived to learn Chinese massage, acupuncture, and cupping, determined to start a “special diagnosis and treatment method” in our village. To this end, she learned the so-called floating needle acupuncture technique, aimed at treating the lower back and leg pain that frequently accosted her elderly patients. She was so elated that she treated the whole family to a feast of king prawns at a restaurant.

Yet despite this pile of certificates, she still had yet to obtain all the qualifications the township health center required of rural doctors. Dr. Han, who was on the verge of turning 50 and would technically reach retirement age in just a few years, still hadn’t managed to fully qualify for her job. Without this, she had no “retirement” prospects to speak of, let alone anything that could be called a “pension.”

She would occasionally happen to run into a younger female doctor who used to work with her in the hospital in town. Through her, Dr. Han heard that her former colleagues were all already looking forward to their “retirement years”—they planned to use their pensions for a life of leisure and sightseeing. Dr. Han felt a pang in her heart. Sometimes, she couldn’t help but rant: “I work just as hard as they do, so why am I the one left with nothing?”

Eventually, Dr. Han went out of her way to avoid meeting her former colleagues in town.

6/7

At the beginning of last year, new instructions came from the higher-ups—all rural clinics had to undergo compulsory renovations. Every item of furniture and equipment, including but not limited to medicine cabinets, tables, stools, blood pressure monitors, and thermometers, had to meet a set of unified standards.

The township health center resolved to carry out a pilot round of renovations at one of their rural clinics, and eventually chose none other than Dr. Han’s. Their decision was probably motivated by the convenient location of our village—it was likely to end up on the itinerary of health inspectors and officials on their random drives down the provincial road.

Thus, Dr. Han had to relocate her practice for a third time. Whether this change was a blessing or a curse for our little clinic was something only Dr. Han could tell.

The town health center attached great importance to this “pilot clinic,” so much so that the director himself approached our village chief and requested that the courtyard belonging to the former people’s commune be vacated for the new clinic. The deal was closed with a cigarette and some enthusiastic nodding. The director took Dr. Han there for a first walk across the venue, detailing to her the general layout of the clinic. Before leaving, he passed to Dr. Han the phone number of an interior designer, instructing her to have him come and take a look: “We want him to do a good job with the facilities.”

Dr. Han was surprised: “Oh, my, they’re even thinking of interior design. It seems that the top dogs are playing serious this time.”

With the approval of the bigwigs, the health center funded all decorations and hardware for the project to advance smoothly and rapidly. Not even a week had passed and the sign of the former people’s commune was removed and replaced with that of the newly designed village clinic.

Inside the brand new clinic, patients were welcomed by a room fitted with a series of uniformly styled items. The large TV in the lounge came equipped with a karaoke mode, and there were separate toilets for men and women. Traditional ink wash Chinese paintings graced the walls of the small courtyard. The entrance gate was flanked by bright sunflower beds, and even the pedestrian crosswalks at the entrance had been painted in a zebra-like, yellow-and-white pattern, reminding passersby that this was no ordinary building.

Needless to say, the “pilot” status of Dr. Han’s clinic came with strings attached—leaders were bound to come and inspect the facilities. The director of the health center instructed Dr. Han to regale the inspectors with a speech that she would deliver in Mandarin while donning a pristine white coat. Dad told me that on the inspection days, Dr. Han got up early to clean up, prepare her materials, and practice her speech. She was so nervous that she paced up and down the yard incessantly.

Authorities were far from being the only unexpected visitors to Dr. Han’s new clinic, now endlessly frequented by a stream of folks eager to check the place out. Dr. Han was tasked with tending to these “tourists,” whether they came on their own or as a group. Furthermore, the inspectors no longer went to all the clinics in the area in turns, but zeroed in on hers as the only stop on their agenda.

All this noise made Dr. Han miserable. After all, she paid all the costs of the equipment, medicine, water, electricity, and more. Her “receptionist” duties were also worth a great deal of time and effort, yet they went largely unnoticed. When she complained, everyone loved to point out that she’d gotten herself a “luxuriously decorated courtyard” at no cost, and was “profiting off what she got for a steal.”

As if that was not enough, Dr. Han was often called to the health center while a superior frowned at her reports and mumbled: “Um…this report of yours…it just isn’t quite up to standards…”

Dr. Han was not naïve. This was, in fact, code for greasing the palm of the bigwig. Every time, she rushed to take out her purse while getting up and shaking hands with the guy in the same breath: “Yes, yes, you’ve really got a point. I will pay more attention next time!” And the bigwig would go, “Think nothing of it, we’re old friends!”

This happened more than once, and each time she’d have to shell out at least 500 yuan.

7/7

After the initial sensation waned, Dr. Han’s clinic returned to its original quietude.

In recent years, at least half of the village’s population had moved out to look for work elsewhere. Dr. Han was now often sitting idle in the clinic for a whole day without a single patient. Even when someone did pay her a visit, most of the times they just wanted to chat. In the past, Dr. Han struggled to find the time to sit down for a warm meal. This was no longer an issue, but now it was her heart that felt empty.

Her plight was likely shared by her peers in similar rural clinics. Gradually, many of these doctors were forced to consider doing side gigs—some even ran express delivery services or small convenience stores in their clinics. However, Dr. Han remained her usual stubborn self, providing traditional Chinese medicine services all while honing her floating acupuncture skills. “I am a doctor. Even if I were to start a side business, it’s going to be related to medicine,” she said. “After all, the clinic sign is still hanging at the door.”

To appease rural doctors, the authorities issued a new subsidy by way of a “public health service fee” of 20 yuan per resident. The doctor in the larger village next to ours received an annual subsidy of up to 40,000 yuan. Unfortunately, Dr. Han only got 10,000 yuan, as our village barely hit 500 residents.

Facing this new disappointment, Dr. Han’s spirits sunk again.

I tried to persuade her, much like Uncle had in the past: “Mom, just listen to our advice. Don’t stay here. Move to the city and open a clinic there.”

Dr. Han promised she’d quit several times, yet never followed through. She simply could not bear the thought of it. Every time, she’d say: “Where would our neighbors go if I left?”

Though there was a modicum of truth to her words, the reality was not quite as Dr. Han depicted. It was true that there were no suitable young doctors to pick up the baton from her at the clinic, but even if she were to leave without a successor, it would just mean a little extra hassle for the villagers to go to the clinic in the neighboring village, or the local hospital just 15 kilometers away.

Eventually, I asked Dr. Han whether it really was just a matter of passion for her. Though I didn’t get a direct answer, she did say: “I’m used to it. I can’t just leave.”

I used to think that Dr. Han’s job at the rural clinic hindered her from taking a wider look at the world. However, now I was forced to come to terms with the likely reality that she was, in fact, willing to remain. In subsequent conversations over the phone, she stated: “Nobody’s spared from ups and downs in their job. You can complain all you like, but the work still needs doing.”

That much was true—Dr. Han had spent her lifetime working as a rural doctor. No matter how many sorrows and grievances she’d faced over the years, it was apparent that the joy, warmth, and honor she’d also enjoyed through her job soothed her and made her reluctant to quit. A memory from a distant winter came to mind. Back then, Dr. Han was called in the middle of the night to assist a child who was down with a fever. On her way back, the road was slippery due to the snowfall and Dr. Han ended up falling. She remained there for a good while, unable to get up. Fortunately, some villagers who had just finished their night shift helped her get back on her feet and safely home. During her recovery, pretty much everyone in our village paid her a visit, with some even calling from outside the village and sending nutritional supplements. Dr. Han was an emotional mess of tears and snot with all this loving attention.

***

Dr. Han was determined to stay, but that did not mean that her difficulties had ended.

In spite of the government’s repeated attempts to reform the rural medical system, rural healthcare is too niche an occupation. Professionals in this field were already in their 60s on average, and their skills were still stuck in the previous century. They earned less than ordinary workers, and dared not go into retirement, as they lacked retirement benefits.

Dr. Han recalls that in late 2018, the government dictated that rural doctors over the age of 65 had to hand over their medical qualification certificates and retire, receiving a meager monthly allotment of 300 yuan in return. This April, Grandma met her fate in this exact way upon turning 65. Her certificate that she’d treasured for years, mailed to her by the government in deference to her status as a first-generation rural doctor, was confiscated. This gesture marked the official end of her career.

Still, Dr. Han smiled and sighed: “Three hundred is better than nothing.”

Nowadays, she spends her days in her small clinic, graced by traditional Chinese ink wash art. She keeps a profusion of potted flowers there.

However, she is far from being idle. She’s just purchased the materials to study for her pharmacist qualification certificate.

Written by You Yu (游鱼)