A town of small-town fortunes by writer Wang Yu

1

Ah Ping suddenly said to me that he wanted to start a grass jelly business in Jianzhen town. I was at a loss for words.

Grass jelly shops were appearing on every street, but I had no idea what the stuff was. It was just like when I first saw a KFC joint, and wasn’t sure whether it was some kind of tire supplier or waterproof paint store. All I knew was that over the past few years, grass jelly had been spreading like wildfire, and that the shop counters were usually crowded with girls.

I didn’t think Ah Ping should jump on the bandwagon. He had never been a trendy person. He usually kept his hair looking like a straw pile, and wore faux leather shoes with saggy nylon pants. Aside from stints delivering water, gas, and newspapers, and doing unskilled kitchen labor, his career history was entirely in food and package delivery. Nothing about him was fashionable.

But he still went into town, signed a lease on a store, and rented an apartment. His determination was obvious.

Later on, Ah Ping’s funds must have been getting tight as he started calling to suggest that I come have a look and join him in business. He said he was getting ready to go big, but first needed me to purchase 10,000 yuan in shares. “Right now, what I need is more manpower,” he said. From his tone of voice, it sounded like this booming venture had reached a crucial stage, and the next step was an expansion in real estate.

I spent a few nights mulling it over before deciding I should give it a try. Who knows? Maybe we would be successful, and have a chain of stores all with plaques above their doors which read “Branch No. XXXX.” Maybe it would even end up a national chain. If that came to be, then at least I wouldn’t have to spend any more time at the lousy termite extermination company. The termite company could go months without a customer, and that year we had only managed to dig up two termite nests. It wasn’t just having to put up with the boss rolling his eyes at me every day. If I stayed, sooner or later I’d turn into a hunk of termite-eaten wood myself.

After exhausting all of my resources, in the end I was only able to put together 8,000 yuan. Half of the money came from winning a bet with one of my boss’s fat family members. I said I could stand an egg up straight on a pane of glass—he didn’t believe I could do it, but I ended up winning (losing wouldn’t have been a big deal, I would only have had to eat a handful of live termites).

Ah Ping was happy to get any amount of money.

2

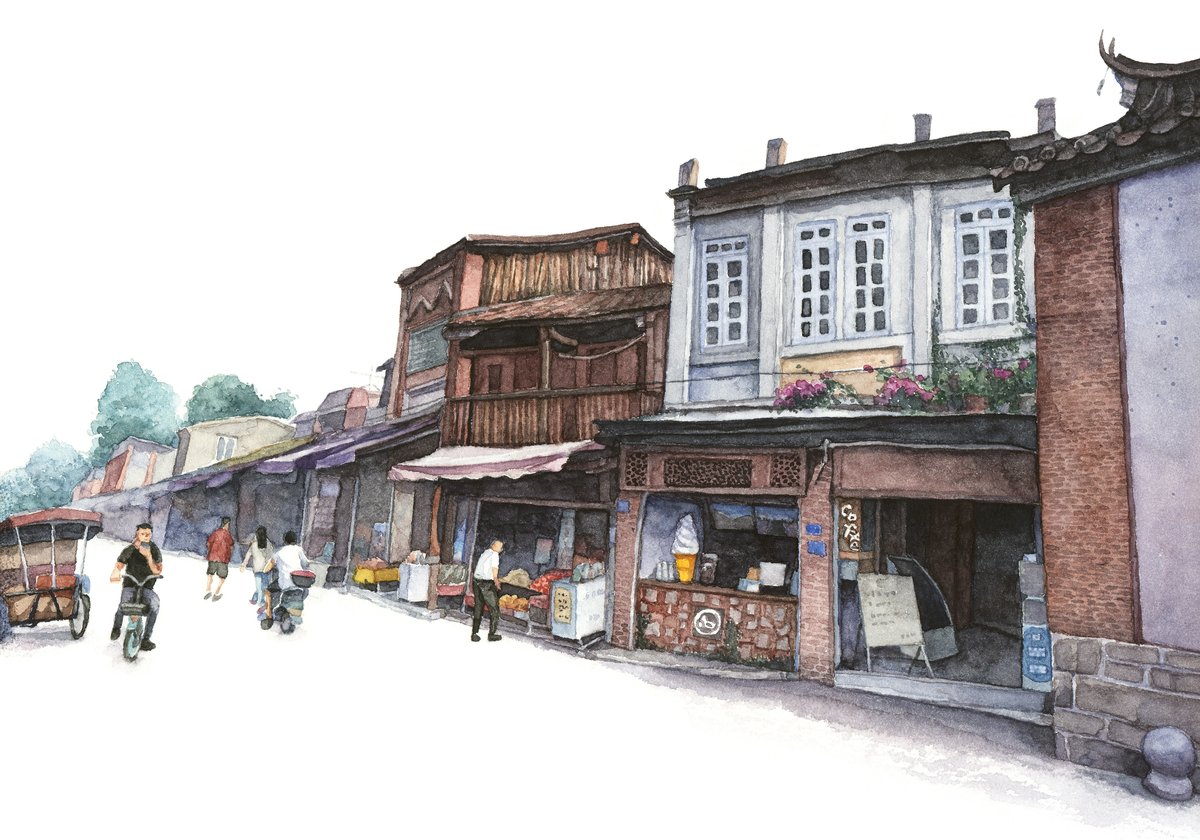

I picked a good day and took the two-hour bus trip to Jianzhen. I had been there many years before. One of my uncles had lived there for a time, and my cousin Guan was still living there. This was a small town in the midst of redevelopment. New buildings were going up everywhere, though some places had kept their old looks: a short street lined with shophouses, a potholed road, a few communal-style buildings from the 1950s or ’60s, whitewashed walls covered in moss, and a dilapidated little church with a shattered cross atop its steeple. Hair salons, photography studios, and incense shops lined the street. A few mom-and-pop shops with old-style counters and shelves sold farm supplies alongside grocery items. In front of these shops were wooden benches, bamboo hats, palm-leaf fans, chicken cages, and even hemp rope for tying up cattle.

The grass jelly shop was located on one of the corners of that old, potholed road. I didn’t know why he had picked that spot. As far as I could tell, the only things in the neighborhood besides a small private middle school were a couple little factories that looked like they were ready to shut down. People on their way to work or school didn’t even take this street. A new road had been built nearby which led to a livelier section of town and a shopping area.

Most of the equipment in the store was prefabricated. The icemaker, sealing machine, refrigerator, and fruit slicer were all installed. The only thing left to do was update the shop sign and storefront. The location had previously been a milk tea shop, but I didn’t know why it had gone out of business. Ah Ping had gotten the shop from a friend of a friend, so the rent was cheap. Ah Ping wasn’t a superstitious person. He was certain that just because someone else’s business had failed didn’t mean that his would, too. “If I don’t try, I’ll never know,” he said. “Consider it a gamble.”

Ah Ping told me confidently that there was no need to spend a lot on ingredients now, because he intended to self-produce them in the future. He was currently in the trial stage, but had been told that his technique was already at a professional level. He handed me a cup as he spoke.

I didn’t know what was in there, or whether it would be a good idea to eat it. It looked like a little bit of everything was thrown in: peanuts, raisins, red beans, taro, and some round slippery stuff that looked like eyeballs. I wasn’t sure if these were the traditional ingredients for grass jelly, or if Ah Ping had decided to express himself. He could get very creative when it came to food. For instance, he had once invented a dish which consisted of mussels stuffed inside a chicken.

It wasn’t until I spotted the heap of black goop in the refrigerator that I finally realized: this stuff was just the mesona herbal jelly we had eaten as kids. Forget Ah Ping—even I knew how to make it, and could even do different varieties. It turned out that all it had taken was to change the name of the stuff and put it in a milk tea cup, and suddenly it was alluring and popular.

“You probably can’t tell, but I’ve included some of my own exclusive special ingredients,” he said, rather pleased with himself.

With extreme caution, I tried a few bites. It seemed like the stuff I remembered. I was impressed by how far he had come along.

“I’ve done the math, and all we need to do is sell at least 15 cups a day to break even. Everything after that is pure profit.”

This left me skeptical, but also eager. Our beachfront retirement homes might all hinge on this stuff.

“I’m going to call the store ‘Ah Ping’s Grass Jelly.’ What do you think?”

It would have to do. I couldn’t come up with a more creative name. If we called it “Ah Ping’s Herbal Jelly,” we weren’t likely to get any customers besides a few constipated grannies.

Despite his planning, the initial overhead was much more than Ah Ping anticipated. Aside from rent and some small renovations, he spent a lot greasing palms to get all the licenses he needed. And that’s to say nothing of the staff he had to recruit.

3

After Tomb Sweeping Festival passed, we flipped through the calendar and picked an auspicious day to finally officially open the shop. As a business partner, I of course had to be there to witness the special occasion.

I’ve honestly never seen such a subdued grand opening as that one. To call it “dreary” wouldn’t have been far off. Looking back on it now, I think it probably cast a shadow over my entire lifetime as an entrepreneur.

First thing that morning, we set up a pair of floral displays on either side of the storefront, and hung a red curtain over the shop sign. To give the whole thing a more ceremonial feel, Ah Ping slaughtered a chicken and bought a slab of pork. He bent the chicken’s neck back and placed it on a tray, then stuck lit incense sticks around the storefront. I went to a nearby shop and bought a few strings of firecrackers. The firecrackers exploded, the red curtain came down, we announced that we were “open for business,” and that was it. We were open.

But the short, dull sound of firecrackers exploding didn’t add anything to the atmosphere. Aside from Ah Ping and me, there wasn’t anyone else even loitering around to watch the show. If it hadn’t been for my sudden idea, we probably would have spent the day standing there like idiots. My idea was to run to the nearest grocery store and buy a few cartons of eggs, then hang a sign on the door which said “New Store Grand Opening Event! Line up and receive a free egg (while supplies last).”

But even with a free giveaway, we were only able to attract a few straggling old folks. Though they waited patiently in line to receive their eggs, not one of them had the thought to visit the actual store. They, too, probably had no idea what “grass jelly” was supposed to be. At their age, they were probably more familiar with the term “pork jelly.”

Our biggest concern was that we still hadn’t found any employees. If I went back home, Ah Ping would be the only one left to man the store. Moreover, just as I had predicted, personal image really was important in such a trendy business. At our age, neither Ah Ping nor I would be fit to stand behind the counter. Especially Ah Ping. Aside from his big hands and feet, he had a receding hairline, was always soaked in sweat, and wore clothes patchy with dust. It wasn’t hard to imagine that our newly opened shop might spend days without seeing a customer.

I suggested to Ah Ping that he try to freshen up his appearance a bit. First was his hair—a good haircut is far more important than most people think. I recommended Ah Ping try something in style, like a quiff or mohawk, or at least add a little color to his hair, anything that would suggest he was fashion-conscious.

But he was way too stubborn and set in his ways. He only reluctantly agreed to wear a baseball hat to cover up his hairline. The rest of him was the same old saggy nylon pants and faux leather shoes which did nothing to hide his greasy character. He looked like a kitchen worker who’d been asked to run out to man the counter.

I naturally thought of my cousin Guan. He had gone to elementary and middle school in Jianzhen, so the town was his territory. But I hadn’t seen him in two or three years, and had no clue if he was still around. I knew him well enough to know it wasn’t wise to disturb him without a good reason. But I thought that asking him to fill in for a few days might be a good idea. There was no way that Ah Ping could handle things alone. I also wasn’t ready to leave the termite company. Though I knew there wasn’t any future in it, I could at least earn some spending money off of Fatty once in a while (the next bet we had lined up was 3,000 yuan if I could eat either live snails or loaches. I planned to feign extreme disgust as I swallowed them down, then vomit all over the place, so he’d think he got his money’s worth).

I called Guan many times before he finally answered. He seemed glum, but he had always been like that. I asked if he was still in Jianzhen, but he wouldn’t give me a straight answer. I asked if he had a job, but he wouldn’t give me a straight answer to that, either. He ended the call by saying flatly: “Tomb Sweeping Festival has just passed.”

I had no idea what significance Tomb Sweeping Festival had to him.

Ah Ping and I put a lot of thought into our brand design. We mostly went with his ideas, from the store’s interior design to the slogans printed on our cups. Some of his slogans included:

“Eat a cup of grass jelly and become a jelly maiden.”

“Eating grass jelly is the only way to become a beautiful woman.”

“The next girl to be picked up on the street by a rich hunk is you, Miss Grass Jelly.”

And on and on, each one more cringeworthy than the last. But what could I do? Simple, direct, and coarse had always been his style.

That’s why Ah Ping and I often had differences of opinion. If anyone ever said I was slightly more cultured than he was, even he would have to agree. But he would also say that culture wasn’t worth shit, and that to make money, you had to know how to cater to the mainstream. You had to be a little tasteless.

Yet to run a business successfully, you had to know how to put up a façade. Just like when you might be out on the street for a bite to eat, and spot a pair of delicious-looking pork knuckles in a display window. At first you think you’re going to get a mouthwatering meal for less than 20 yuan, but instead you’re served a few thin strips of hog’s head meat while those pork knuckles sit undisturbed in the display window. Ah Ping didn’t understand this part of business.

We set our opening hours from 11 a.m. to 10 p.m. In reality, after 8 p.m. there wasn’t anybody on the street aside from old men smoking water pipes in front of the storefronts, and the occasional woman walking her dog. A group of guys on motorcycles often rode over to play pool in front of the photo studio, but they never cared to try any grass jelly. They preferred going to the mom-and-pop shops to drink beer that tasted like pesticides. Aside from all these people, I often saw a girl with an afro striding down the street. She never seemed to pay any attention to our grass jelly shop.

Since business started, the only customers we had each day besides a few random middle school students were some elementary school students who used the free Wi-Fi to play games but never bought anything. The women who worked in the nearby factories never seemed to care much for leisure, plus most of them were on the older side. In the mornings and evenings they were always on the opposite side of the street, hurrying back and forth.

I felt we had no choice but to change strategies. We couldn’t just focus on selling to the young and hip, we had to expand to the broader public and children. Our method was this: we’d place a pot of tea eggs and zongzi for sale at the front door, plus add a display of lollipops, potato chips, and other snacks.

After opening the shop, the only one of my ideas which Ah Ping readily took up was to add two quail eggs to the grass jelly. This would provide the customer with a nice little surprise. Ah Ping thought that this was very creative. But really it wasn’t creative at all. You could put anything you wanted in grass jelly, just as long as the thought came to you.

4

We still hadn’t found anybody to hire. I had Ah Ping make a more visible “Help Wanted” sign, with the words “Good Pay” written in big letters.

Soon after, a girl came into the store. She looked a little familiar. I thought for a moment, then realized that she was the girl who walked alone and confident past the store every night.

It was hard to say whether she was attractive. She kept her hair in an afro, below which she, for some reason, had also tied two ponytails. She wore wide leg jeans with holes in them and a pair of platform shoes. She was slightly olive-complexioned, and her t-shirt revealed a small portion of her chest. In what seemed to be an attempt to make life difficult for herself, she wore horseshoe-sized hoop earrings, which would have been extravagant enough if not for the addition of some kind of small white plastic birds or chickens which she hung from the hoops.

Based on her haircut alone, we called her Afro Girl.

As for Afro Girl’s pay, Ah Ping and I had already done a little research and decided to start her off at 2,000 yuan a month. Compared to local standards, the amount wasn’t exploitative. My base salary at the termite company wasn’t any better. Plus, we offered four days off per month and a free lunch every day (prepared by Ah Ping personally).

After our store’s opening, I tried to find time to visit at least once or twice a week. This gave me a sense of responsibility that I never had before. It was the kind of feeling that gave a person ambition and hope for the future.

To make the store’s atmosphere livelier and increase our popularity, I put up a confession wall beside the seats opposite the front counter. The goal was to attract young couples to visit the store every day and express their love for one another. I didn’t really care for this kind of lowbrow creativity, but to make money, I was willing to be a little lowbrow. It’s a matter of fact that the depth of one’s culture is inversely proportional to one’s wealth.

I had no choice but to introduce that lowbrow creativity everywhere.

I thought that Afro Girl could take on the big responsibility of the confession wall. Mainly because I had no idea what to paste up there. I had no imagination when it came to that sort of thing.

Afro Girl didn’t let me down. Shallow love notes flowed easily from her fingertips:

“Bunny loves Piggie. From Anonymous.”

“So-and-so, I love you, love you, love you, love you… Love you forever.”

“I can turn into whatever you want, because all I want is you.”

“The world is yours, and you are mine.”

Reading them made my hair stand on end. There were some that almost seemed deep:

“Honey, all I want for this year’s Qixi Festival is to climb a mountain and hear you say those three little words.”

Some were even slightly poetic:

“I’ve seen the sun freeze over, but I’ve never seen you. I’ve seen rivers flow backwards, but I’ve never seen you. I’ve waited for snow flurries in summer, but I’ve never waited for you…”

“Hey, boss, when do I get a raise?” said Afro Girl. The straw in her mouth squeaked as she chewed.

“Don’t call me ‘boss,’ it’s tacky,” I said. “Maybe you can call me ‘director.’ Ah Ping is technical director, and I’m marketing director.”

“‘Director’? Who do you think you are, Steven Spielberg? Ha ha!”

She was always immature like that. Almost every time I saw her, she was sipping on a lemonade and humming a tune, her gaze drifting off into some other place, taking her mind along with it. You could never know what she was thinking—it was like she was sleepwalking in the daytime.

Afro Girl wasn’t a local, nor did she live nearby. She lived on the edge of town. She didn’t like riding a bike, so she walked more than half an hour to work each day. She walked faster than most girls, of course. The reason we had often seen her walking by the store was because she had been helping a friend feed her pig in the mornings and evenings. At first I thought she was talking about one of those little pet pigs. But it actually weighed more than 100 kilos and was still getting fatter. The friend had gone on a business trip and asked Afro Girl to feed it for a few days.

“If I feed him but he doesn’t eat, I hit him with a stick,” she said. “Sometimes I’d really like to slaughter and eat him. All he eats is rice and vegetables, so he’s all natural.” The experience had led her to change her screen name to “FeedThePig&Sleep.”

When she was in a good mood, she could talk about anything.

“You wanna hear something? There’s a girl where I live who sleeps with her landlord to pay for rent,” she said. “I couldn’t do shit like that.”

With your whole vibe, I doubt the thought would ever cross your landlord’s mind, I thought to myself.

“Hey, Spielberg, tell me the truth: how many women have you got?”

She seemed to actually take me for some kind of boss or landlord character. Sometimes her remarks would really make you mad. But I wanted to play it cool, like I was an 80,000 yuan stakeholder in this grass jelly store. In a position like that, you couldn’t show your weak spot to anyone, not even to a girl like her.

“Women, huh? Probably too many to count,” I said.

Since putting up the confession wall, Afro Girl had learned how to turn it into a convenient tool for expressing her personal opinions. She would make stickers as eye-grabbing as possible, and paste them in the most prominent spots:

“With such low wages, it’s no wonder this dump can’t hire anybody. Serves you right! Your bosses are too stingy.” Signed “Stranger A.”

“You know, your crappy store could close up earlier, there’s hardly anybody around here after 8 o’clock.” Signed “Mimi Rabbit.”

She didn’t even bother to disguise her handwriting, but still thought that no one could tell it was her. I still laugh when I think about it.

5

If we wanted to expand, we had to find another employee or two. But since hiring Afro Girl, no one else had come in to ask about a job, not even for part-time work.

I thought again about Guan.

Although Guan had a sort of quirky temperament, he didn’t dress too out of fashion, kept himself clean and presentable, and was even a few years younger than Ah Ping and me. This made me think that he would be suitable for the job. But most importantly, the work didn’t require any hard thinking. He couldn’t stand anything that required a lot of thought. I understood that about him. But despite the shop being open for more than half a month, I still hadn’t seen any sign of him. Perhaps he wasn’t actually in town. I had no way of knowing what he was doing. After pestering him with repeated phone calls, he reluctantly agreed to give it a shot. But he had one condition: he wanted to get paid by the day.

Given Guan’s peculiarities, we knew it was best to agree. We paid him 80 yuan per day, slightly higher than Afro Girl. We didn’t have any other choice. At that point, if a lady selling vegetables or an old night watchman had come in to ask about the job, I doubt I would have considered hiring Guan.

A few days later, Guan finally showed up. He looked like even more of a ne’er-do-well than he used to. He seemed half-dead, as if he was missing a kidney, but at the same time drugged out, his gaze just as distrustful and piercing as always.

In any case, we were finally taking a step in the right direction. We looked more like a real shop, and business was gradually starting to pick up—we were selling more than 30 cups a day, at least twice Ah Ping’s initial goal of 15.

Even though business was sluggish, it was the variety of people that, to me, kept those days from feeling ordinary. If I could have been 10 years younger, I would have preferred to spend the rest of my days minding a little shop like that one, where I could make a living doing whatever I was in the mood for.

On Lixia, the first day of summer in the traditional calendar, rain showers throughout the day had turned to wind in the evening. The ground was covered in overripe fruit that had fallen from the few mango trees that lined the street. From the night wind that carried the sweet smell of mangoes, a figure emerged, guitar strapped across his back. He seemed to have traveled far, and looked exhausted. He must have been a wandering busker. A talent with no opportunity. He wore a small ponytail at the back of his head. All musicians, filmmakers, oil painters, and hairdressers like to wear small ponytails. I thought Ah Ping might also try wearing one.

“I’ll have a soda water,” he said.

“We don’t have any soda water here.”

“Then I’ll take a beer.”

“We don’t have beer here, either.”

He was disappointed, maybe even a little sad.

Finally, he drank a free glass of warm water. Perhaps to express his gratitude, he took the guitar off his back, tuned it, then began to strum a song and sing:

Under these lights with a waning tipsy feeling I wish would never end,

There’s no need for sudden recollection.

A search begins in the night, and ends on the horizon,

So much desolation and lowliness is all the same,

Hidden like scars of the past.

In this moment I am naked in the night and wind,

A drifter in the darkness,

One with the stray dogs and scavengers.

To flee or to endure, neither can move the curtain of night,

I only wish for a body as light as a dream.

…

I could hear that the lyrics were a poem, no wonder they seemed familiar. It was a posthumous work by a poet who had died young. At night in this lonely town, an atmosphere like this one was hard to come by. I suddenly felt a little emotional. I hadn’t felt such a way in a long time, so long that it was as if I had forgotten I was someone who could be moved by something. Even if the music hadn’t attracted any customers, and even if the only audience was Ah Ping, Afro Girl, two women walking their dogs, and me, I still thought the singer wouldn’t feel disappointed knowing that at least one person had been moved by his music.

The next day, an old man who practiced feng shui came into the shop. He also asked for a glass of warm water. He drank it while talking nonsensically. Afterwards, he looked all around, then told us the shop’s location wasn’t very good. Something about a missing corner and two clashing directions, a nearby incense and candle shop which hid too much yin energy, and numerous other unfavorable elements.

Afro Girl wanted to ask if he could also tell her fortune, but when she saw Ah Ping’s face turn the color of pig liver, she figured it was best to shoo the old fellow out the door.

Ah Ping had never believed in superstition. The previous year he had worn a red windbreaker while delivering packages. Though it was his zodiac year, he hadn’t worn red to ward off bad luck. He simply thought it made him look livelier, plus it helped him better evade cars and pedestrians.

“It doesn’t matter whether you believe in it or not,” said the old man as he walked out. “But on New Year’s Day and the Lantern Festival, you’d best remember to burn some joss paper in front of your store.”

Later, I overheard one of the dog-walking women say that people had died in the store a few years prior. A middle-aged couple had apparently killed themselves inside. The store was a wonton shop at the time. The whole neighborhood knew about it. I asked Afro Girl, but she didn’t seem to know anything. Guan was the same. He had only heard from his dad that there used to be a coffin-maker on the same street. Besides traditional Chinese coffins, they also made six-sided ones that looked like the cardboard boxes that ham came in. The coffin-maker had stayed in business until 1992, though Guan hadn’t started attending school in town until 1994.

6

Afro Girl and Guan’s relationship had changed. If I hadn’t seen it myself, I wouldn’t have believed it. They had been like fire and water at first. Afro Girl thought that Guan couldn’t do anything right, and at the very least neither seemed to show any interest in the other. But in less than a month they had become like a young married couple with a tacit understanding. I saw it all the time: one would churn ice while the other added water, or one would collect trash while the other wiped down tables. All the while they would talk, laugh, and hum songs.

I also never expected that someone like Afro Girl could have a gentle side, perhaps even a motherly side. For instance, she would make food without anyone asking and leave a portion for Guan, thoughtfully putting it in the rice cooker to stay warm. Even more startling was when Guan came down with a mild fever. She called him four or five times that day, telling him in a gentle, quiet voice what medicine to take, when to take it, and how much to take, her tone like that of someone lecturing a child.

Guan was the most surprising. He somehow shook off his listlessness and became sunny, steadfast, and diligent. Previously showing up only in the afternoons, he now came in to work on time at noon. He shaved every day and kept his hair neat. Sometimes he would even make witty remarks.

Neither Ah Ping nor I could understand the logic behind these changes. Over and over I tried to imagine—how would it feel to hold someone like Afro Girl in your arms? Like a swollen puffer fish? A dragon fruit covered in mustard? But Guan had actually done it, and moreover seemed completely smitten with her.

Compared to the new district on the east side of Jianzhen, our street was so lifeless it seemed abandoned. On an average day, most of the people around (besides a few women with children and farmers selling vegetables) were elderly. It seemed like the whole street was packed with old folks.

But even in a place like that, there were still people who came to collect protection money. On the night it happened, Ah Ping wasn’t at the store, and neither was Guan. Out of the corner of her eye, Afro Girl spotted two little hoodlums who looked like they hadn’t even grown pubic hair yet. Without raising her head, she swiftly grabbed two knives off the kitchen rack—one a paring knife, the other a cleaver—and slapped them down on the counter.

“You motherfuckers, get the hell out of here! Don’t interrupt me while I’m playing games!”

Apparently, the two kids tried to look tough by spitting on the floor, then sulked out the door. It wasn’t likely that anything would happen in such a small town. Anybody with prospects had already left to make their mark on the world.

When evening came, our area was the first to start getting dark. Aside from the occasional group of motorcycles that revved past, drunks would sometimes make a racket nearby. A few stray cats in heat would howl, and small musical troupes would sing traditional Cantonese songs.

Sometimes we’d also get some business. Girls from the hair salons and nightclubs would stop by for a beverage on their way to or from work. They would say things that made Ah Ping flush and cause Guan’s mind to wander, though Afro Girl never let Guan stare at them.

All in all, it was a quiet and lonesome street. Lonesome enough that you could smell the odor of manure in the air as it wafted up from the vegetable fields in the surrounding villages.

7

It was the peak season for termites, but I was becoming less interested in that work and often thought about quitting. I felt like I had already become my own businessman.

But Fatty didn’t want me to leave. He liked to search for termite nests with me (my technique for finding nests was top notch), and he would often drag me out for late-night meals and massages. He liked to make bets with me all the time, sometimes even losing money on purpose. Of course, he mainly gambled for fun, while I did it for the money. His title was Director of Engineering, but he didn’t have any idea what he was doing. He’d mistake water stains for termite tracks, and termite tracks for water stains. He even thought that termites were the precursors to hornets, and that once all termites “grew up” they would sprout wings and lay eggs that would hatch termites. He didn’t actually need to do any work himself, all he had to do was show up. But he insisted on personally searching for termite nests, and didn’t allow the use of insecticide (he liked to eat deep-fried termite eggs, and to soak them in liquor). Several times he had torn up people’s hardwood floors to find termite eggs. He left the floors looking like freshly plowed fields, but never managed to find even a single termite.

I guess people always rely on one another for success. Just like me with Fatty, and just like the grass jelly shop with Afro Girl and Guan.

Guan probably never would have thought that at our small shop he would find true love for the first time. All the women he had dated in the past had either run off with his money or gotten him involved in multi-level marketing scams. He’d even suffered physical injury. As a result, he had almost completely given up on love and women those past few years. Now, work and love had helped him change from a zombie back into a normal person. No longer did he look like he was missing a kidney, and instead of a distrustful, piercing gaze, his eyes now hid a little gleam of satisfaction.

8

Then came the day when a guy with a knife-scarred face showed up at the grass jelly shop on a motorcycle.

“Hey! All this time I’ve been searching, and there you are! When are you coming back with me?” He stared hard at Afro Girl.

“No one’s going anywhere with you! Buzz off, I don’t know you.”

Ah Ping and Guan were both there at the time. But having no idea what was going on, neither said a word.

Then, Afro Girl threw a cup of lemon water and some other objects. After pulling out a paring knife and screaming “Get lost!” repeatedly like a crazy person, the knife-scarred guy finally started his motorcycle and rode off.

“Okay, okay… you just wait,” he said.

But the following month was calm, as if nothing had happened. Business even started picking up. Perhaps the quail eggs in our grass jelly had brought us more attention. Ah Ping placed a square table and three rotating stools in front of the shop, and tastefully hung up two wind chimes.

On the Dragon Boat Festival, Ah Ping gave Afro Girl and Guan half a day off so that they could go to the nearby Yong’an River to watch the dragon boat races.

“That river is really narrow and has a bend,” said Guan. “Every year boats flip over. I like watching them flip—everyone does.”

“Sometimes a whole bunch of boats flip over!” said Afro Girl. “Not that it’s a big deal if they do. At worst, the crew swallows a few mouthfuls of stinky water. The winners get to eat a whole roast pig.”

“Actually, even if they don’t win, they still get to eat roast pig,” said Guan.

Hearing them talk, I wanted to check out the races, too. But Ah Ping was planning to slaughter a chicken and make fried taro with pork, so I had to watch the shop.

A few girls who looked like middle school students came by to eat. They all stared down at their phones playing games while chewing on squeaking drinking straws like Afro Girl.

An old man came by to ask if we had any zongzi and mugwort leaf. The vegetable market was sold out. I told him that we didn’t sell zongzi or mugwort leaf, only herbal jelly.

“Herbal jelly? That stuff is as black as tar,” he said. “How do you manage to eat that out of a cup?” The girls giggled as they listened.

All of a sudden I felt that this old street was actually pretty nice. It was certainly a little run-down and unfrequented. But it was precisely the fact that it was a run-down, stone-paved street that made people walk a little slower and take in the sights, like the palm-leaf fans, chicken cages, bamboo hats, and hemp ropes.

On the Double Sixth Festival, the summer heat kept Ah Ping up all night. He got up early, worried that the ice in the shop had melted. As he prepared to open the shop door, he found spots of congealed blood in the doorway. Thinking it was pig blood left by the butcher delivering pork from the market, he wiped the spots away with his shoe. A little past 11:00 a.m., Afro Girl and Guan hadn’t shown up. Ah Ping called them, but both of their phones were off. There was still no sign of them after 1:00 p.m.

It was two police officers who eventually showed up. They were looking for Afro Girl and Guan.

“Were you aware that they stabbed someone last night?”

“Stabbed someone? Who?” Ah Ping asked.

“Apparently it was the girl’s fiancé. They’re from the same hometown. He’s in the hospital now—they’re not sure if he’ll make it.”

The younger officer took some pictures of the bloodstains and around the shop.

“Which one stabbed him?” Ah Ping asked.

“They both did. Are they your employees?”

“They were temporary help.”

“Do you know where they are?”

“No. I tried calling them earlier but couldn’t reach them.”

“Where do they normally reside?”

“I really don’t know. I don’t even know their real names. I’ve always just called them by their nicknames.”

“If you have any information, you need to notify the police department. Remember, if they aren’t found, your shop here is going to be considered partially responsible.”

9

The shop finally had to close down. Besides the families of Afro Girl and her fiancé, police officers, detectives, protection money collectors, and other random people all started showing up. None of them were friendly, none were the type you wanted to offend.

What’s more, the building would soon be torn down. A public notice had been put up announcing that the area was going to be turned into commercial real estate with a shopping plaza and entertainment facilities. It turned out that the residents of Jianzhen were remarkably all in support of the construction and very excited for it. In less than half a day they had all signed the eviction papers, and that evening some people had even set off fireworks.

In total, the shop had been in business for a little over three months. Exactly one season. To a grass jelly shop, everything hinges on a beautiful summer season, and ours had just seen the start of one. But summer was far from over when our shop went out of business.

It had been like a fleeting dream.

But it didn’t matter. People always find a way to move on. As for me, at worst I would head home and make a few bets with Fatty again. I’d eat some snails or other weird stuff, or, if my luck was good, maybe I’d find something valuable while digging for termite nests under the floor of a fancy old house.

Of course, it was hard for Ah Ping to accept the truth so suddenly. Opening the store had exhausted all of his savings and passion, plus it would be hard to find another place with such cheap rent. But after a few days, he felt relieved.

There would be other opportunities. We’d just have to wait for the day we could make our comeback.

Afro Girl and Guan had disappeared like mist. We never found them, nor could the police. I hope no one ever finds them.

Ah Ping and I returned to our previous lives. He went back to delivering packages, and I went back to searching for termite nests.

Only when we’re drinking together do we reminisce about the days of Afro Girl and the grass jelly shop.

Who knows, maybe she and Guan went somewhere to start a real life. Maybe they started a business, opening a less expensive grass jelly shop of their own. And who knows, maybe they’ve gotten even more creative, and found some other sort of egg to put in their grass jelly.

Author’s Note:

The character “Ah Ping” in the story is based on a friend I’ve known for many years, who goes by Ah Ping in real life. In reality he never opened a grass jelly shop, but did run a small fast-food restaurant which closed down in less than a year. The reason it failed wasn’t just because he couldn’t find a partner (except for a temporary guy very similar to Guan), but also may have had to do with his poor cooking skills and a rent hike. He also never paid much attention to small details and, like his character in the story, didn’t put any effort into his personal appearance. He has since returned to his old line of work delivering packages. All things considered, he worked very hard within the small cracks of the big city, without ever achieving a great deal. There are many people like him in the “urban villages” within big cities.