For one short period in 2001 and 2002, China’s men’s soccer team was the pride of a jubilant nation

As the ball dropped to Yu Genwei inside the penalty area of a raucous Wulihe Stadium on October 7, 2001, the crowd held their collective breath. Then, the 27-year-old forward stretched to fire the ball past the Omani goalkeeper and into the net, sparking wild celebrations in the stadium in Shenyang, Liaoning province, and in the living rooms of millions watching around China.

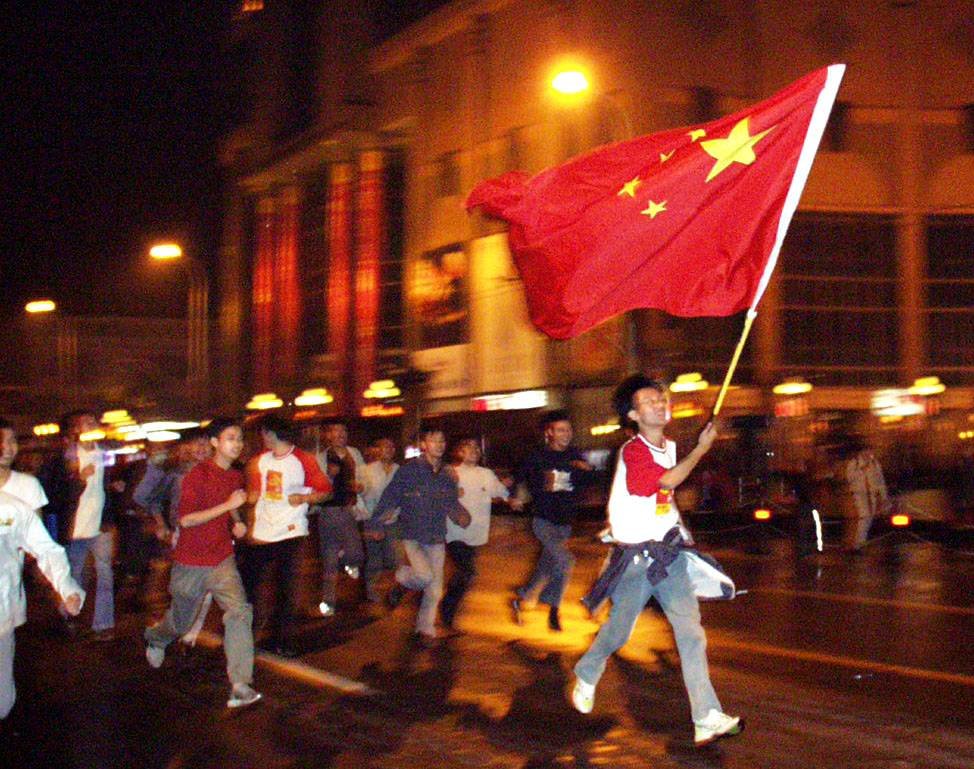

When the final whistle blew, Yu’s goal gave China a 1 – 0 win over Oman; enough to send the men’s national team to the FIFA World Cup for the first time in its history after over 40 years of trying, and to bring supporters out onto the streets all across China, celebrating with fireworks, flags, whistles, and singing.

“In Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Xi’an, Chengdu; in cities all over, in villages, all of China’s fans can be proud and happy with this team,” the presenter on CCTV 5, the state-run sports channel, told viewers as celebrations began. In Beijing, TV footage confirmed crowds gathering outside Beijing Railway Station to watch the match on a big screen, then spilling onto the streets around Tiananmen Square to revel in the team’s victory. Drummers performed in Haikou, people sung the national anthem in Chongqing, and fans danced long into the night in Qingdao. “We’re Through” read a giant headline on popular sport newspaper Titan Sports.

After a special training camp in Kunming in April 2002, a squad of 23 players along with coaching staff traveled to take part in the first-ever World Cup held in Asia, jointly hosted by Japan and South Korea, on May 26. Since returning to international soccer competition in 1957, China had never qualified for the men’s World Cup. But 20 years on, 2002 remains the only year the PRC has appeared at the quadrennial tournament.

Sun Jiahui, a Liaoning native (and long-time TWOC contributor) who now lives in Shenyang, was glued to her TV screen the night China played Oman in 2001, when she was 11 years old. “I remember watching that game with my family...they weren’t really fans but they would watch the game and get caught up in the atmosphere,” she tells TWOC. Once China’s victory was confirmed “there were firecrackers going off” in the neighborhood, “and people outside celebrating, extremely happy.”

Inspired by China’s team and their qualification, Sun bought newspapers and sports magazines around the time, cut out pictures of her favorite players and reports and pasted them on her bedroom wall.

The competition in 2002 ended in failure for China, with the team failing to exit the group stage, losing all three of their matches and failing to even score a goal. But the memories of that glorious night in Shenyang, and later the thrill of seeing China at what is the world’s most popular sporting competition, remain ingrained in the minds of fans like Sun.

It came at a time when the country was also celebrating winning the right to host the 2008 Olympics and entering the World Trade Organization in 2001. “Even though they didn’t score a goal, I still felt very proud,” Huang Yiwen, a soccer fan in Fujian province who was 34 in 2002, tells TWOC. “It was the first time I’d experienced China playing in a global competition, not just Asia, making their first step on the world stage, even if just a small step.”

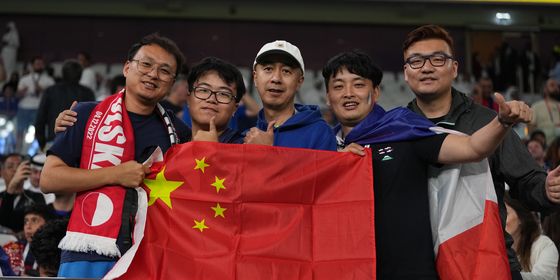

Looking back on the 2002 World Cup, Li Xiang, a sports journalist at the time, told Southern Weekly earlier this year that it was the first time soccer became widely popular in China, and established the World Cup fan culture that still sees fans traveling to Qatar for matches at this year’s tournament, despite China not being present. “That year, everyone I knew would follow the World Cup, everyone would talk about soccer,” says Sun. The events of 2001 and 2002 introduced a whole new crowd to soccer in China.

Sadly though, it remains the high point of Chinese soccer history, with failures aplenty since then, and the game in the country perpetually in crisis. Many of the players who played for China at the World Cup, once heroes, have become embroiled in scandal since then. While money poured into China’s top professional league, attracting foreign players on huge contracts, and even naturalized players have been sought for the national team, little progress has been made cultivating domestic talent capable of playing at the top level in European leagues.

At the tournament, China had another chance to make history by winning a game or, with some luck, advancing past the group stage (where they were drawn with Costa Rica, Turkey, and Brazil). Some like Sun even dared to dream the impossible: a World Cup win. “We had these dreams...if we could win one [match] and draw one, maybe we could get into the last 16,” Sun tells TWOC.

Huang had more realistic expectations: “win one match in the group stage, and score a goal.” Huang explains that that year the national team “was united, energetic, determined, and enjoyed their soccer.” “All the conditions were favorable,” he says. “Japan and Korea didn’t attend the qualifying matches [because they entered automatically as hosts]...and we had an international standard coach.”

The matches in 2002 were broadcast in the daytime in China, a novelty for fans used to watching European games late at night and in the early morning hours. Even in school, World Cup fever was everywhere for a couple of weeks. “I was in class [when China was playing], but some of my classmates had one of those portable radios...and in another class someone brought in a TV from home,” Sun recalls with a chuckle.

“Later the teachers found out about it, but they didn’t stop it. In fact, there was tacit permission from them for everyone to listen,” she says. “During the third game against Turkey, the teacher joined in and listened to the match with everyone else and stopped teaching.” In the normally studious and strict environment of Sun’s middle school, such relaxed attitudes from the teachers was very rare.

Huang watched the games while on duty at the township enterprise where he was employed as an industrial statistician. “The bosses watched with us,” he says. For matches in the evening, “I watched on TV with colleagues in our work dormitory, whilst drinking alcohol...each match we would drink at least six bottles of beer each,” Huang recalls. “I was full of hope for the Costa Rica game, that we could win 1 – 0. But reality isn’t the same as hope.”

In China’s first game, against Costa Rica in Gwangju on June 4, the team dominated possession but lacked the precision needed to grab a goal, and eventually the Central American team’s superior finishing shone through. China lost 2 – 0, leaving it facing the formidable task of taking points off Brazil (then four-times world champions) and a strong Turkey team.

Against Brazil, China quickly fell two goals behind. Then, in the 37th minute, the ball found its way to captain Ma Mingyu close to Brazil’s goal at a packed Seogwipo Stadium on South Korea’s Jeju Island. Could Ma provide a moment of celebration and what would surely be China’s finest ever soccer moment against one of the world’s most formidable national teams?

Sadly, Ma rushed a shot, blasting the ball high and wide of Brazil’s goal. The moment was gone in a flash, and so was China’s chance of gaining something from this vital match. Brazil racked up two more goals to win the game 4 – 0. “If I had just relaxed, moved my position slightly, it would have been a totally open goal. An amazing chance, [but] I was hasty. It was a shame,” Ma recalled years later in an interview with Southern Weekly. Huang remembers, ruefully, watching another shot by China that hit the goalpost.

In their final match, against Turkey, China again lost, this time 3 – 0. “I watched the game at a food stall,” says Xue Lingqiao, an editor from Nanjing (and another TWOC contributor) who was just 5 years old in 2002. Watching the World Cup with his father is Xue’s earliest soccer memory. “Many people were gathered together, drinking, sitting on a long bench shoulder-to-shoulder just to watch a tiny TV the stall owner had set up. The owner said if China scored a goal they would give a 10 percent discount.”

As the match ended, the stall owner got to keep their 10 percent, and the excited atmosphere seeped away: “Many people fell silent and even cried,” Xue recalls.

China left the tournament having earned no points, no wins, and no goals while conceding nine. But its presence in the games was still a historic achievement, with many of the players from that era still remembered fondly around the country. Xue was inspired to play soccer and has followed it ever since.

As for China’s World Cup players: “People felt sorry for them, they felt it was a shame, but no one seemed to scold them,” Sun recalls, contrasting to today’s fans who regularly vent their anger on social media at the men’s national team’s repeated failures to get close to qualifying for another World Cup. The team’s then-head coach, the charismatic Serbian Bora Milutinovic (known as Milu in China), is still considered a hero by many fans for leading China to the World Cup. His pithy principles, such as “attitude determines everything” and his commitment to “happy soccer,” became well-known slogans for fans at the time.

For one summer Chinese soccer was the pride of the nation. But the team’s fortunes deteriorated quickly afterwards. In 2012, Qi Hong (formerly Sun’s favorite player) and Jiang Jin, two members of China’s World Cup squad, were arrested for taking bribes and match fixing and sentenced to up to six years in prison. Just last month, Li Tie, who played in 2002, spent part of his career at Everton in the English Premier League, and was China’s national team coach until December 2021, came under investigation for corruption offenses.

On the pitch results have deteriorated year by year. Not only has China’s men’s team failed to reach another World Cup, they have fallen behind many of their rivals. In March this year, the team lost 2 – 0 to Oman, the same team they beat two decades ago to reach the World Cup; and even lost to Vietnam, a team ranked 96th in the world, in February. “In the ‘90s, China was the third-best team in Asia,” says Huang. “Since then, we’ve gradually got worse.”

“I thought the 2002 World Cup was a brilliant beginning for the national team,” reads a comment posted this year under footage of China’s 2002 match with Costa Rica on Billibilli. “I never thought it would turn out to be a pinnacle unsurpassed for 20 years.”