Founded on June 16, 1924, China’s first modern military academy aimed to reunite a divided nation. It didn’t quite work out that way.

Looking out over rows of aspiring young military cadets on an island, not far from the bustling docks at Whampoa in Guangdong province, the great revolutionary Sun Yat-sen felt a stirring of hope for reigniting his vision of a unified Republic of China.

China in May, 1924, had gone grievously off-piste from the nation Sun was credited with founding over a decade ago. It was fragmented into regional satrapies ruled by warlords. Far away, in the former imperial capital of Beijing, a rotating cast of warlord-adjacent politicians took turns as the nominal president of the republic. When Sun proclaimed the cadets as the inaugural class of the Whampoa Military Academy on May 1, it was the latest in a long series of schemes and strategies to revive the fortunes of the Kuomintang (KMT), the political party he co-founded.

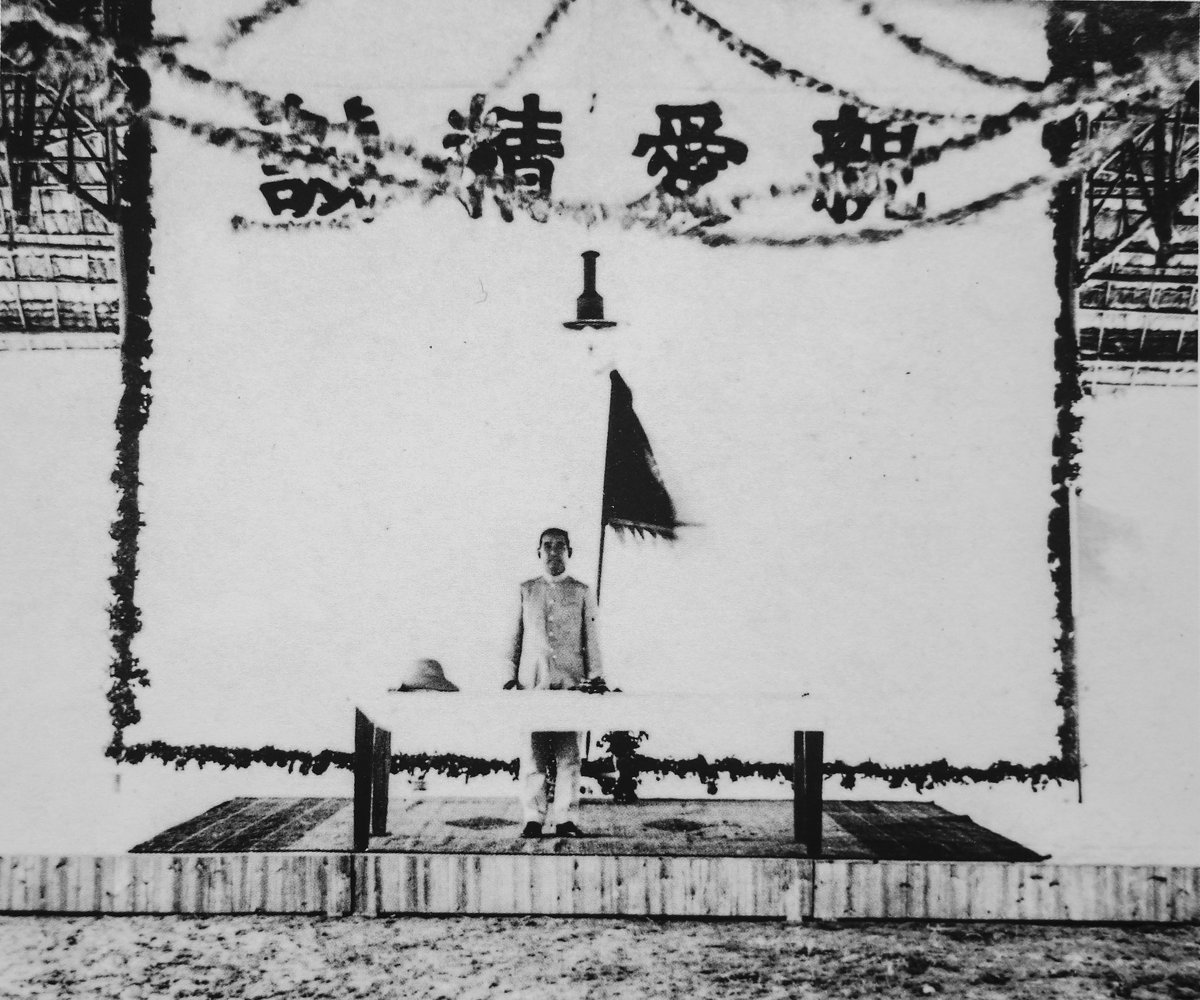

Chiang Kai-shek and Zhou Enlai with cadets at Whampoa Military Academy around 1924 (Wikimedia Commons)

It would also be one of Sun’s last significant acts as the head of the KMT. Within a year, the great revolutionary would be dead, succumbing to cancer in a Beijing hospital. It would be left to his protégé Chiang Kai-shek, the recently installed commandant of the Whampoa Academy, to realize—if only partially and temporarily—his mentor’s dream.

On June 16, 1924, the cadets reported to class for the first time. Their instructors included up-and-coming officers from the ranks of the KMT, but these young men, some not much older than their students, lacked field experience. To make up for this, Chiang and Sun employed veteran military advisors from the Soviet Union who had experience fighting in the Russian Civil War and defending the Soviet Union against the 1918 Allied Intervention.

Why Soviet advisors? The idea of establishing a party military academy to strengthen the KMT as a force to unify China and expel the foreign powers had its roots in discussions between Sun Yat-sen and representatives of the Comintern, particularly Hank Sneevliet, three years earlier. The Soviet agents convinced Sun that for China to be strong, it needed to be led by a strong party. A strong party must possess a strong army led by a core of well-trained officers loyal to that party. After years in the political wilderness, flitting from one fickle warlord ally to another, Sun was ready to make the KMT a military power to compete with the warlords.

But the main reason that Sun turned to the Soviets was that Sun felt to accomplish his goal on an accelerated timeline, he would need the support of one or more of the foreign powers, and the Soviets were the only ones taking his calls. Other nations had little interest in helping the KMT’s anti-imperialist agenda.

In turn, the Soviet leadership had ideological reasons for assisting nationalist and anti-colonial forces in Asia. Losing their colonies would mean the Western capitalist nations would no longer be able to rely on colonial markets and commodities. In other words, Britain, France, and Germany couldn’t export their exploitation across oceans. The capitalist chickens would come home to roost, as Marx had predicted.

But Soviet support came with a request. While the Soviet leaders and the Comintern were pessimistic about the revolutionary potential of the newly formed Communist Party in China, they recognized the small but ambitious group as kindred spirits worthy of their support. If the KMT wanted Soviet help, they had to ally with the Communists. Many of Whampoa’s students and faculty—including academy political commissar Zhou Enlai—would eventually play leading roles in the Communist Revolution.

It was Sun Yat-sen, named honorary Premier of the Academy, who held together a diverse and divided campus. The motto of the Academy was “Camaraderie.” Sun’s inaugural speech that day emphasized unity, courage, and perseverance in the effort to “save the country.” But it was Sun’s leadership that held the coalition together. There was an uneasy alliance of KMT leaders with different visions for the party, including not just Commandant Chiang but also Wang Jingwei, Hu Hanmin, and Liao Zhongkai.

Many of the students who were present in 1924 at Sun’s welcoming speech would later become part of the “Whampoa Clique,” including future KMT commanders Chen Cheng and Du Yuming, as well as the man who would one day become Chairman Mao’s erstwhile “Closest Comrade at Arms and Heir Apparent”—Lin Biao.

The academy also took in students from Korea and Vietnam. A well-traveled young Vietnamese revolutionary named either Ly Thuy (or another alias, Nguyễn Ái Quốc, depending on who was asking), gave talks and speeches at the academy many years before adopting his most famous nom de guerre: Ho Chi Minh.

The faculty and students who attended Whampoa Military Academy in its early years forged a brotherhood united by camaraderie and the spirit of Sun Yat-sen. Unfortunately, that brotherhood would be shattered by Sun’s untimely death in 1925. With the loss of his mentor, Chiang Kai-shek turned to his growing “Whampoa Clique” to outmaneuver his intra-party rivals and replace Sun as head of the KMT. The Whampoa students—KMT and Communist alike—would form the core of the 1926 Northern Expedition that unified much of China under Chiang’s rule. Once ensconced in his new capital in Nanjing, Chiang turned against the Communists and leftist elements in the KMT. Thousands died at the hands of Chiang loyalists in the Shanghai Purge of 1927.

The relationship between the parties would never be the same. From 1926 to 1949, long periods of bloody fighting and competition were interspersed with the occasional uneasy truce or shaky “United Front.” There were many reasons for the bitter and acrimonious split, including ideology and geopolitics.

And there is the lingering “what if?” What if Sun Yat-sen had not died at 59 but had lived another 10 to 15 years? Would he have been able to hold the coalition together, or were the ideological forces and the tide of history too strong even for someone of Sun’s stature?

The Academy’s legacy is more than a training ground for future commanders. It was also a place, no less so than China’s more famous universities, for exchanging ideas among young people who would later play important roles in shaping modern China, if not the world. In the brutal conflict which divided China beginning in the 1920s, one of the many tragedies was the way that people who had studied together, partied together (in both senses of the word), and been the foundation of one of China’s most famous military academies, would one day be standing on separate sides of the battlefield.

As with the US Civil War, when graduates of the United States Military Academy West Point led their troops into battle against their former classmates, the bloody struggle for the soul of China divided a generation, a reminder that no fight is as personal, fierce, or complicated as that which is fought between brothers.