How did Chinese students earn the right to choose their own majors, and how did the most popular choices evolve over time?

When Lin Xueliang took the gaokao (national college entrance exam) in 1955, students did not have the option to choose their own majors—that privilege was not extended until after the early 1960s.

Lin, who is now a teacher in Hubei Province, just took the exam and was told he had been accepted by Huazhong Normal University, which at the time trained students to become teachers. The nationwide list of university freshmen was later published in the People’s Daily newspaper, and that was how Lin discovered he had been selected to study biology. He cut out the scrap of paper with his name on it as a souvenir, and headed off to the college to register.

In 1966, the Cultural Revolution began, and a political frenzy engulfed the nation. The gaokao was cancelled and was not reinstated until more than a decade later, in 1977. For that first batch of post-Cultural Revolution students and those who immediately followed them, math, physics and chemistry—often referred to as shulihua (数理化)—were the most respected majors.

During that time, working class was still deemed the most desirable class status, and the most eligible bachelors were workers and soldiers. When Huang Mingjian graduated from high school in 1977, he picked chemistry over English—the only two majors available to choose from in his school—explaining as the basis of his reasoning that “if I studied chemistry, I could work in a factory.”

Students running experiments at the Nanjing Institute of Chemical Technology in the late 1970s. Chemistry, along with other majors in math and the sciences, exploded in enrollment numbers after students began to choose their own majors. (VCG)

And then there is the tale of the mathematician Chen Jingrun (陈景润), one of the most idolized people of that decade, whose story captured the imagination of a generation of youngsters. Chen is famous for his work on an unsolved mathematical problem known as Goldbach’s Conjecture, as well as “Chen’s theorem,” a paper he published in 1966. He remained obscure until a group of foreign experts asked if they could meet him as part of a visit to China in 1978.

Shortly after their meeting, famous writer and poet Xu Chi (徐迟) wrote up Chen’s story; the piece was published in both the People’s Daily and the Guangming Daily, two of the most influential state-run newspapers. Xu portrayed Chen as a genius, untroubled by material hardship and insensitive to the prospect of political persecution. Xu’s story served to redefine the nation’s image of a desirable man—a thin, bespectacled nerd who was so absorbed in his own world that he would walk into a street lamp and apologize to it.

Chen became no less an idol than Taiwan pop starlet Teresa Teng, and in the process, so did math. One of the most famous quotes from the story read: “Math is the queen of all sciences. The crown of math is math theory. Goldbach’s Conjecture is the pearl in that crown.” His popularity, combined with Deng Xiaoping’s call for young people to “march forward towards the modernization of the sciences,” produced a slogan that can still be heard in schools today: “Learn math, physics and chemistry well, and you can walk the world without fear” (学好数理化,走遍 天下都不怕。).

Wang Yunlai, now a Nanjing University professor, recalls in an interview with the Jinling Evening News, “At that time, there was a very strong sense of division between the students of different majors. When we took the train back home over the holidays, those studying math, physics and chemistry seemed especially proud, while those of other subjects were more humble, because their majors betrayed their poor performance in high school.”

For 20 years after the gaokao was reinstated, university and college students didn’t need to worry much about finding jobs. These, too, were often allocated by the government, much in the way that majors used to be. Yan Chunyou, a philosophy professor at Beijing Normal University, recalls the 1980s as an age of innocence in terms of academic choices. “As students, we didn’t need to worry about the future, and the university didn’t put a lot of emphasis on publishing essays. All we needed to do was to learn.”

The ’80s were also a rare time when literature and philosophy were considered vital to Chinese people’s daily lives. Poets like Gu Cheng (顾城) and Haizi (海子) were heroes, and people were fascinated with the works of whichever philosophers they could find in translation: Hegel, Sartre and Nietzsche, for example. In this more liberal atmosphere, majors like literature and philosophy began to attract a new wave of talented students.

“In the wake of the Cultural Revolution, people were very sensitive to literature and philosophy. In the three years after the resumption of the gaokao, a lot of students voluntarily applied to major in philosophy,” Yan says. “But nowadays, few students apply to our department. We can only recruit a dozen undergraduate students each year, and most of them are tiaojisheng (调剂生, students transferred because their scores were not high enough for the departments to which they originally applied).”

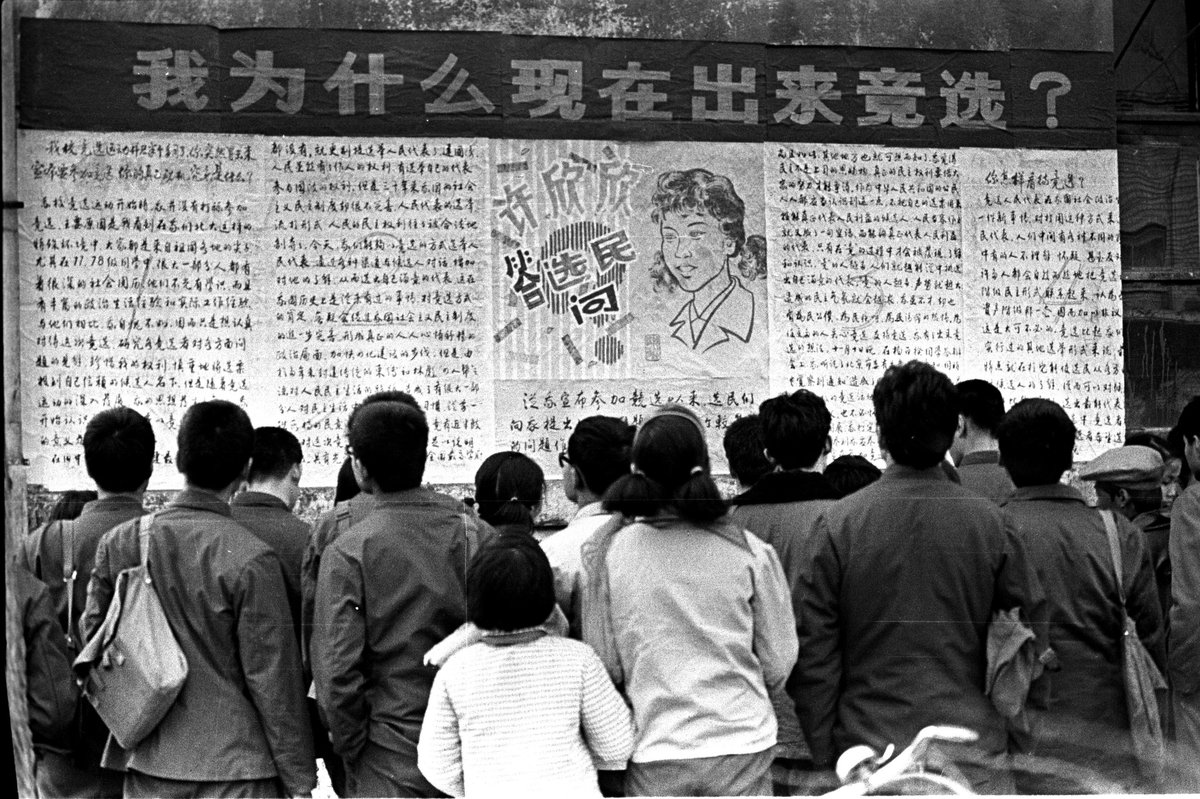

Romantic patriotism was another inspiration for young people to learn philosophy. Yang Qunsheng, who studied philosophy at Zhongshan University in 1978, recalls in a memoir about his campus life, “At that time, the philosophy departments were seen as the cradle of [future] political leaders. Not long after we entered school, the Party held the Third Session of the 11th Central Committee and announced the Reform and Opening-Up policies. All my classmates were excited and discussed both openly and in private where China was going and what we could do. We all felt the future of China rested on our shoulders.”

But it was not long before pragmatism took the place of idealism in terms of choosing majors. In the mid-1980s, as the government put more emphasis on implementing democracy and the rule of law, a career in the legal profession began to appear more promising, and eager students began to sign up for law courses.

Government policy was also instrumental in spurring a spike in the number of majors that included an “international” element. Towards the end of the 1980s, as the government gradually relaxed its controls on exports, the number of economic and trade departments in universities mushroomed. By the 1990s, the competition for enrollment in “international economy and trade” courses was so intense that only those with the highest admission scores could find places. Another far-reaching change in policy occurred in 1998, when the state drastically reduced the quota of graduate jobs that it would allocate directly, rapidly increasing the number of independent graduate job-seekers from just a handful to about 70 percent of the total.

In the same year, the government laid down the kuozhao (扩招) policy, which significantly expanded university enrollment. In 1999, the population of university freshmen increased nearly 50 percent over the previous year, and was to rise steadily in the years immediately following the new policy.

While the increased number of places eased the difficulty of being accepted by a university, it ratcheted up the pressure in terms of finding a job. Some majors that appeared promising for future careers when students first applied emerged as disastrous choices by the time they graduated.

Software engineering was a case in point. Just before kuozhao was introduced, it was such a “hot” major that one-third of ligong (理工 science and technology) students were enrolled in majors related to software engineering and IT, according to the Ministry of Education’s journal China University Students’ Career Guide.

When Zhong Xiaofei started at the engineering department of Huazhong Science and Technology University in 2000, his freshman class was a “who’s who” of students with the highest gaokao scores. However, when he graduated in 2005, he found himself a member of an ever-expanding troop of so-called “IT peasant workers (IT民工).”

The term was a self-deprecating joke for the army of young programmers emerging from China’s universities, who, while usually well-paid, routinely work 12 hours a day in order to safeguard their positions from the hordes of eager graduates just itching for the chance to take their places.

In 2010, the number of software engineering students was four times that of 2004, and by 2011, there were more than 1,000 universities and colleges with software engineering departments, according to Qiuxue, a magazine that gives guidance on the gaokao.

But though the size of enrollment surged, the quality of education failed to keep pace. The “MyCOS Blue Book of Employment in 2011,” a report by an education consulting firm, warned students off studying software engineering in a college for vocational training, as opposed to a university, as they were very likely to graduate without employment.

Legal studies were another victim of the kuozhao policy. Zhou Wanfang graduated from the law department of Peking University in 2005, and naturally tried to find a job where she could make use of her degree. She worked a few such jobs, but eventually settled down as an executive assistant.

“If you want to stay in the law business, the competition is brutal and young people have to scratch their way from the very bottom,” Zhou says. “A lot of young lawyers and legal assistants are living a hard life, earning about 2,000 yuan per month, and with no bright prospects. Only a handful of lawyers can eventually become successful.” A popular saying among Chinese lawyers is that 80 percent of all the wealth in the trade is generated by just 20 percent of the lawyers.

Math, once “the queen of all sciences,” was also on the watchlist of MyCOS. The old popular saying has now been irreverently revised: “Learning math, physics and chemistry well is not as useful as having a good dad” (学好数理化,不 如有个好爸爸 Xuéhǎo shùlǐ huà, bùrú yǒu gè hǎo bàba).

All of this made the choices facing 15-year-old Wang Jinwen all the more difficult as she prepared to enter high school in the fall of 2012. Already worrying about her choice of major, she struggled to decide what she should aim for, as she has had to focus so hard on extra studies.

“My summer vacations have always been taken up by buke (补课, extra classes)—math, physics, English. I’m only good at math, but I wouldn’t say I love it,” she explained.

While the idea of having your major and job chosen for you may seem strange today, it certainly allowed a generation young Chinese to grow up free of the soul-searching that torment many in the market economy as they strive to find their place in the world. Now, the reality of facing these tough choices is coming home to a new generation of youngsters, who are still asking themselves the same difficult questions as Wang: “I’ll only be 18 years old when I take the gaokao. How can I know what major is right for me?”

This is a story from our archives. It was published originally published in 2012, and has been edited and republished in honor of TWOC’s upcoming 100th issue celebrations. Check out our subscription plans and discounts that will give you access to more great stories!