From cram academies to meeting celebrity scholars, preparation for ancient China’s civil service exams was both similar and different to test-prep today

As one of the most (in)famous parts of China’s modern education system, the gaokao, or university entrance exam, shuts down entire cities every June. Construction is halted, square-dancers are muted, and even barbecue stalls in the city of Zibo are reportedly closing in order to not distract students before what’s said to be the most important exam of their life.

Chairman Mao once said, “Fight no battle unprepared (不打无准备之仗),” and this saying is often quoted today to refer to the superstitions and “gaokao factories” (intensive test-prep high schools) that some students and their parents resort to for exam success.

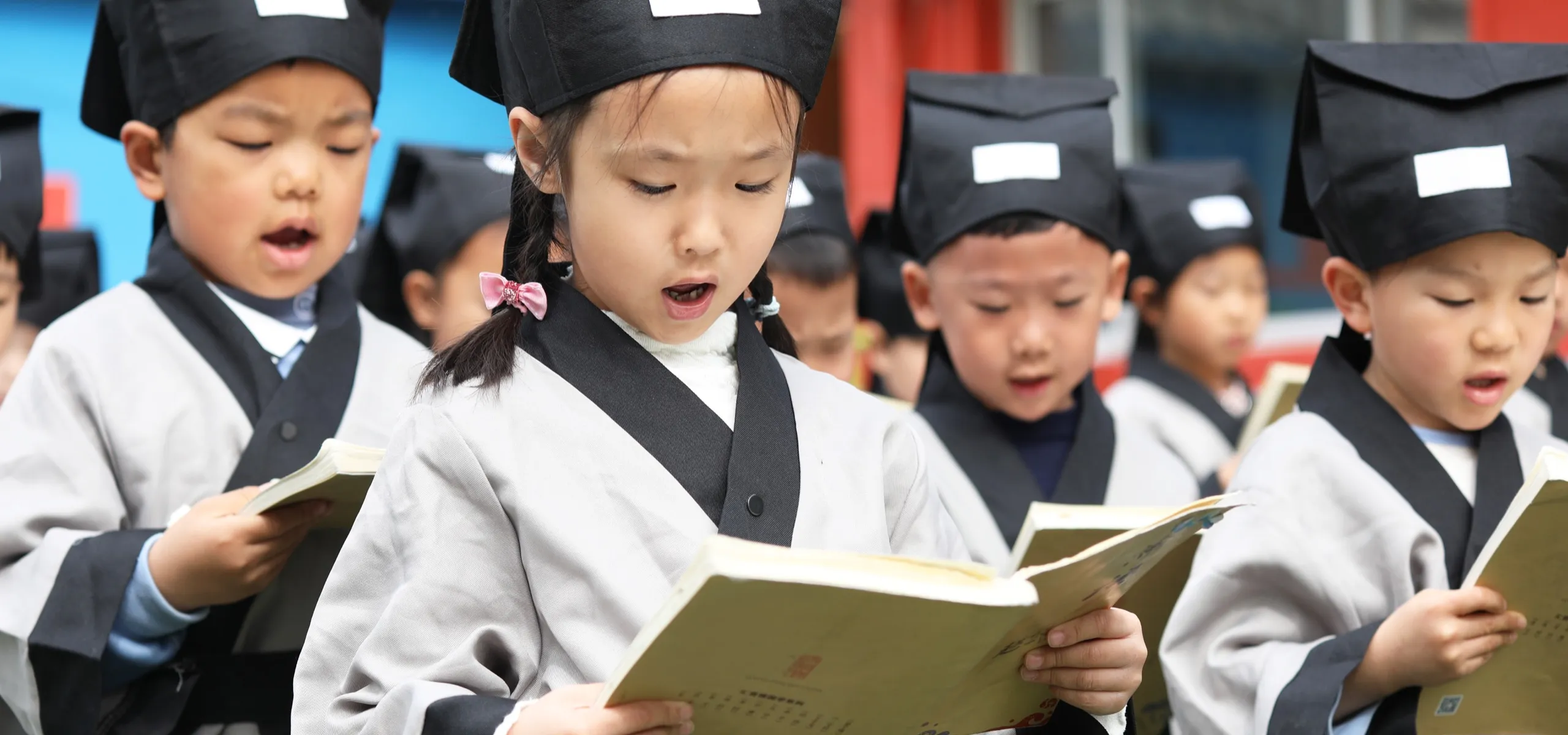

Some of these methods had their historical equivalents in the keju (科举), or examinations for selecting civil service officials (which even had a test for children), while other ancient test-prep methods were rather unique:

Test-preparation courses

Just like today’s cram schools (until they were outlawed by the “double reduction” policy two years ago), there were also test preparation courses for keju examinees. These were mainly offered by private academies, or shuyuan (书院), founded by famous Confucian scholars. First appearing in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), shuyuan were originally places where scholars could teach the classics and spread their academic wisdom. But as the civil service exam system became standardized, test-preparation gradually became a major business for shuyuan.

The Lize Academy (丽泽书院) founded by famous scholar Lü Zuqian (吕祖谦) in the Southern Song dynasty (960 – 1279) was a very successful test-prep institution. Besides teaching basic knowledge and test skills, Lü even compiled a textbook for the keju, called Study on The Commentary of Zuo (《左氏博议》). The book contained 168 essays based on the historical text The Commentary of Zuo (《左传》), and each essay could be used as a model for answering the “discourse on politics” section in the exam.

It’s said that the book was popular among young scholars, who gave it the name “Yellow Book (黄册子)” due to its yellow cover. But it also attracted criticism. Liu Fu (刘黼), a scholar and government official of the Southern Song, wrote in a poem: “What’s the meaning of this shabby yellow book? Its only function is to help people come out on top in an exam. (区区黄册子,所事惟夺魁).”

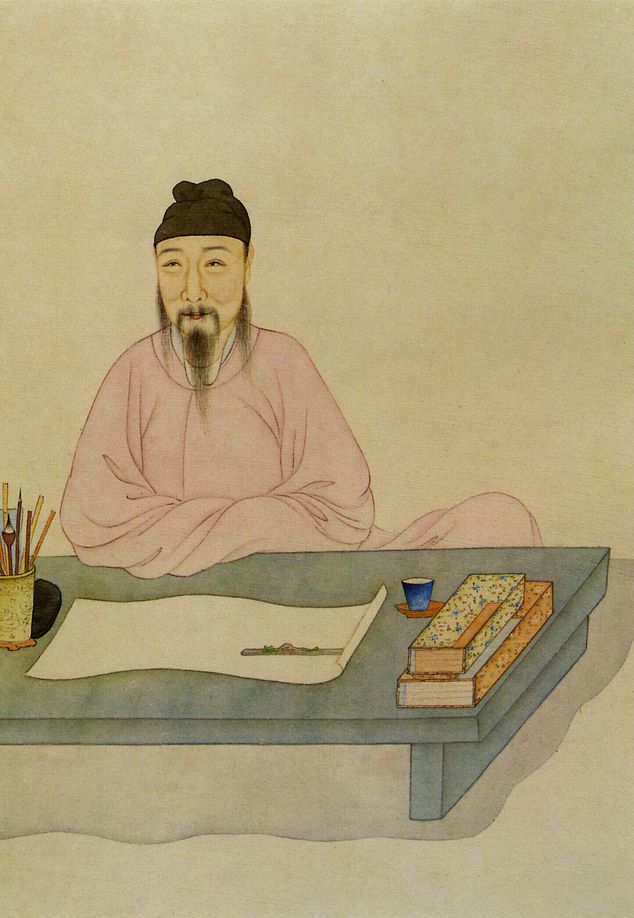

Networking with celebrities

In the Tang dynasty, there was no such thing as a double-blind review. That meant that if the examinee could leave a good impression on the examiner before the keju, their answers might be judged more favorably. A common practice was to send one’s essays or poems to celebrities in academic circles who were likely to become examiners. If their works impressed, the examinee would probably be introduced to the examiner.

Poet Zhu Qingyu (朱庆馀) once did this successfully. Before he took the keju, he happened to meet Zhang Ji (张籍), a famous poet and government official. After an enjoyable conversation with Zhang, Zhu left dozens of his essays and poems for Zhang to read. Zhang took them and left without saying a word.

A few days passed with no response from Zhang, so the younger academic wrote him a poem, titled “To an Examiner on the Eve of Examination”: “Last night red candles burned bright in the bridal room; at dawn the bride will bow to new parents with the groom. She whispers to him after touching up her face: ‘Have I painted my brows with fashionable grace? (洞房昨夜停红烛,待晓堂前拜舅姑。妆罢低声问夫婿,画眉深浅入时无?)’” In this poem, Zhu likened himself to a bride, Zhang to the groom, and the chief examiner to his in-laws. In this subtle way, Zhu asked Zhang about his attitude toward his works.

Zhang then wrote back a poem titled, “Response to Zhu Qingyu (《酬朱庆馀》)”:“A girl from Yue looks into the mirror after putting on her makeup; knowing herself beautiful, but she is still not confident. Those women in expensive silk outfits are not valued in the heart of current people; but the singing of the Yue girl is worth ten thousand gold (越女新妆出镜心,自知明艳更沉吟。齐纨未足时人贵,一曲菱歌敌万金).” Zhang likened Zhu to a beautiful girl from the Yue region and expressed his appreciation for Zhu’s talent. These poems brought Zhu great fame, and Zhu passed the exam successfully.

But this practice could backfire sometimes. In the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), two young men called Tang Yin (唐寅) and Xu Jing (徐经) visited a scholar and official named Cheng Minzheng (程敏政), who was also an examiner, before the keju. On that year’s exams, one essay question stumped every candidate—except Tang and Xu. As a result, they were arrested and accused of bribing Cheng to tell them the exam questions in advance.

Though no solid evidence was ever found, the two young men were both deprived of their qualifications and barred from ever taking the keju again. However, Tang is remembered today as a great poet, calligrapher, and painter, and Xu became great-great-grandfather to the geographer Xu Xiake—perhaps proving that exam success is not everything.

Eating properly

Today, before the gaokao, some students choose to take one fried dough stick and two eggs for breakfast, signifying a score of 100. In ancient China, food with auspicious names was also an important part of exam preparation. For example, the “Zhuangyuan Cake (状元糕),” a specialty of Zhejiang province, was popular, because it shared a name with zhuangyuan (状元), the title conferred on the candidate who came first in the keju. The cake got its name because it looked similar with the headdress worn by zhuangyuan.

In Guangdong province, there was also a dish called “zhuangyuan porridge (状元及第粥),” which was porridge with pork entrails. Its origin was attributed to Lun Wenxu (伦文叙), an actual zhuangyuan of the Ming dynasty. It’s said when Lun was young, he was poor and made a living by selling vegetables. The owner of a porridge shop pitied the young man, so he ordered vegetables from Lun every day. When Lun arrived to deliver the vegetables, the shop owner would make him a bowl of porridge with the leftover pork organs. Years later, when Lun grew up, he took the civil service exams and became a zhuangyuan. He went back to visit the kind shop owner, and named his meal “zhuangyuan porridge.” After that, eating zhuangyuan porridge before the exam became a fashion among scholars.

Worshiping the “god of exams”

Compared with eating food with symbolic meanings, worshiping a god might be a more direct method to pray for exam success. There were many deities examinees could pay respects to before the big day, be they from Buddhism, Daosim, or folk beliefs.

One god that examinees worshiped was the bodhisattva Manjusri, who represents transcendent wisdom in Buddhism. There was also Wenchang (文昌帝君), a Daoist deity known as the God of Culture and Literature in Chinese mythology. Another choice was the Kui Xing (魁星), also known as “Great Kui the Star Lord (大魁星君).” He was believed to be the Deity of Examination, and his name, 魁, literally meant “chief” or “first.”

If you were an atheist, though, there was only one option—Confucius. As the founder of the Confucian school of thought, Confucius was respected as “the teacher of all ages.” Even the state would organize grand events to worship Confucius before the keju, praying that the sage could bring good luck to all his disciples.

Poems translated by Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)