Learn all about a Chinese character that can be both close and far

The period before the founding of the first imperial dynasty in 221 BCE is considered a “golden age” of love in ancient China: Nearly one third of the 300 or so poems and ballads from the 11th to 6th century BCE collected in the Classic of Poetry (《诗经》) talk explicitly about romance and marriage.

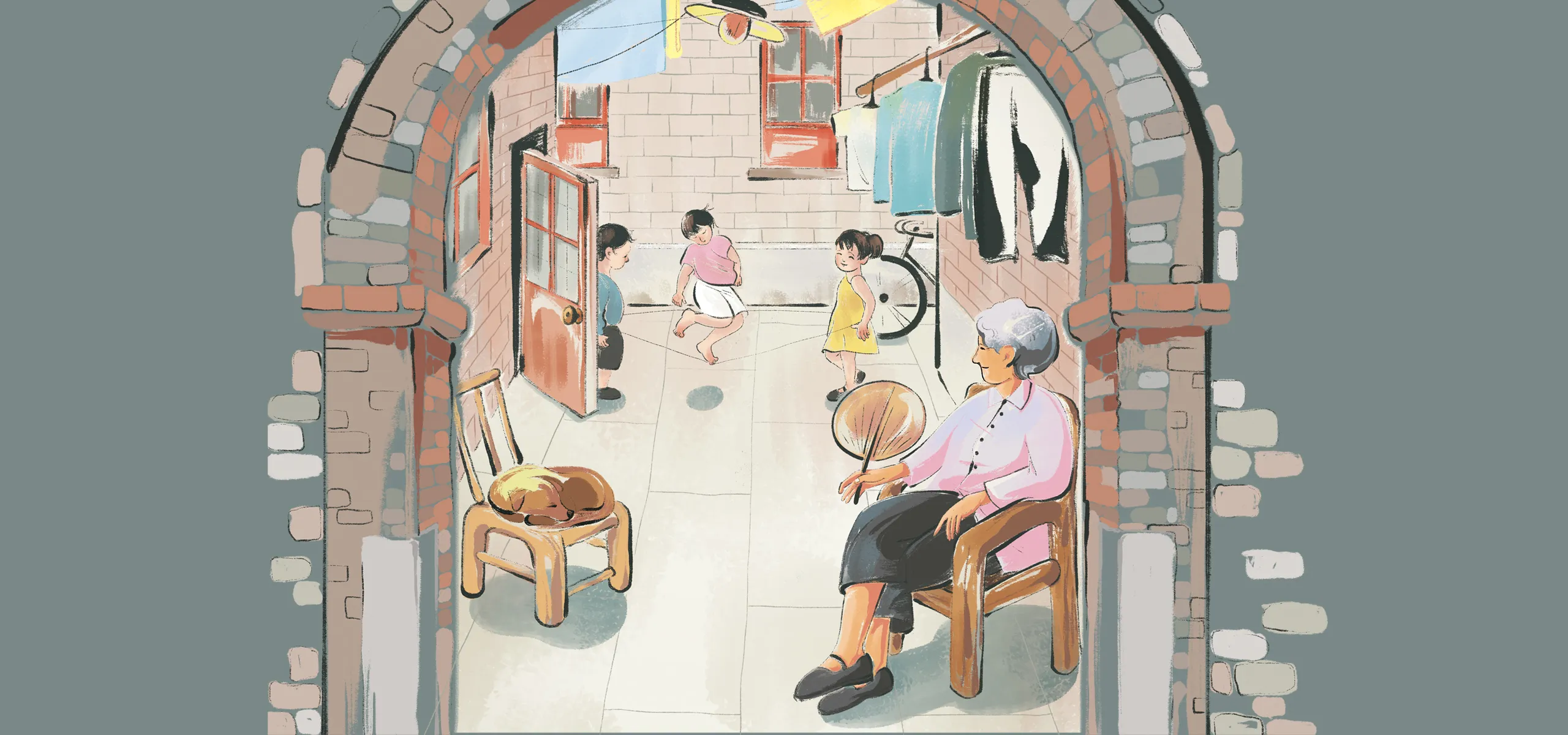

As Song dynasty (960 – 1279) scholar Zhu Xi (朱熹) concluded in his analysis, “[Pieces in] the ‘Airs of the States’ [one of the three sections] of the Classic of Poetry are mostly ballads, where men and women chant their feelings to each other. (凡诗之所闻风者,多出于里巷歌谣之作。所谓男女相与咏歌,各言其情者也。Fán Shī zhī suǒ wén Fēng zhě, duō chūyú lǐxiàng gēyáo zhī zuò. Suǒwèi nán nǚ xiāngyǔ yǒnggē, gè yán qí qíng zhě yě.)”

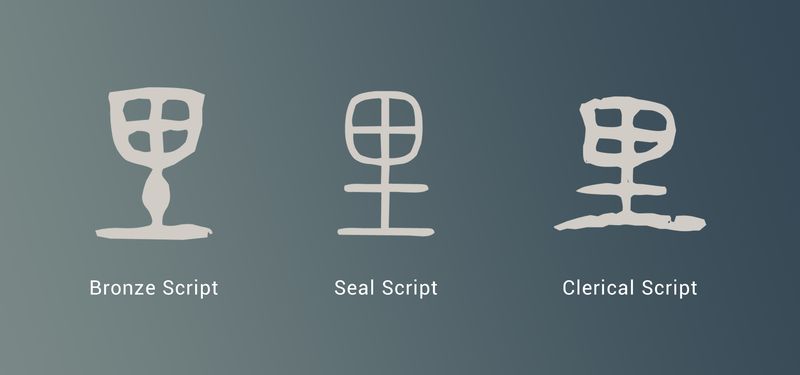

The character 里 (lǐ), which Zhu used together with 巷 (xiàng) to metaphorically mean “among the people,” first appeared carved into bronze around 3,000 years ago and consists of the radical 田 (tián, field) on the top and a 土 (tǔ, soil) below. According to the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220) dictionary the Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》), “里 indicates where people live (里,居也 Lǐ, jū yě).” In the poem “To Zhongzi (《将仲子》)” from the Classic of Poetry, a woman warns her lover Zhongzi “not to intrude my residence (无逾我里 wú yú wǒ lǐ),” even though she misses him, for fear of her parents’ reaction.

The character’s meaning extended to include neighborhoods and neighbors, as in 邻里 (línlǐ) and 里巷 (lǐxiàng, alleys or lanes), or 里弄 (lǐlòng) in Shanghai dialect, which is why the gossip exchanged among neighbors is called 家长里短 (jiācháng lǐduǎn, household trifles). In ancient China, 里 even became an administrative unit comprising 25 households, and the official in charge was a 里长 (lǐzhǎng, “head of li”).

The neighborhood has been a vital social unit throughout Chinese history. In The Analects (《论语》), Confucius states: “It’s beautiful to live in a neighborhood that’s filled with goodness. How can someone be wise if they choose to live in a place that lacks goodness? (里仁为美。择不处仁,焉得知?Lǐ rén wéi měi. Zhé bù chù rén, yān dé zhì?)” Likewise, philosopher Mencius’s mother moved their residence three times, from a place near a cemetery, to a marketplace, and then a school, to give the child Mencius a better environment for growth, paving his way to become a great thinker.

里 is now used to refer to someone’s hometown: 故里 (gùlǐ) or 乡里 (xiānglǐ, home village or town). The homecoming of a person who has achieved great things, or 荣归故里 (róngguī gùlǐ, return in glory), is welcomed, while officials who 鱼肉乡里 (yúròu xiānglǐ), or oppress local people, are condemned.

The character also serves as a measure of distance: one 里 is around 500 meters, and a 公里 (gōnglǐ) is one kilometer; while 里程 (lǐchéng) refers to mileage. The Great Wall is known as 万里长城 (Wànlǐ Chángchéng), as it stretches thousands of kilometers, and 千里马 (qiānlǐmǎ), which originally referred to a horse that can run a thousand miles a day, is now often used to describe people with huge potential.

Many place names in Beijing include the character 里 based on their distance from the nearest city wall. For instance, Sanlitun (三里屯, literally “three li village”), now a popular shopping district, gets this name as it is about three li away from Dongzhimen Gate.

With the reform to promote simplified Chinese in modern times, 里 is also used as a simplified version of 裹 (lǐ), which originally indicated the lining of a piece of clothing, and then a location or direction, often inside or near a subject, as in 城里 (chénglǐ, in town) and 屋里 (wūlǐ, in the house). “Here” is 这里 (zhèlǐ), “there” is 那里 (nàlǐ), and “where” is 哪里 (nǎlǐ).

While it’s easy to comprehend the inside of a physical object, understanding the internal thoughts of someone’s heart or mind (心里 xīnlǐ) remains a challenge, especially if they think one way but behave in another (表里不一 biǎolǐ bù yī). Perhaps that’s why ancient Chinese put so much emphasis on romantic poetry 2,500 years ago—it was the best way to express their true feelings.

On the Character: 里 is a story from our issue, “Small Town Saga.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.