Learn about a character that’s been fostering connections since ancient times

Festivals can be a headache for many Chinese. Peak seasons for celebrations and ceremonies, holidays also often mean, as per tradition, giving out money to relatives and friends. Even for long-lost schoolmates one hasn’t contacted, or (联系 liánxì) in Chinese, for years, gifts have to be handed over at, say, a wedding. After all, humans are social animals, and such human 联结 (liánjié, connections) have bound people together in China for millennia.

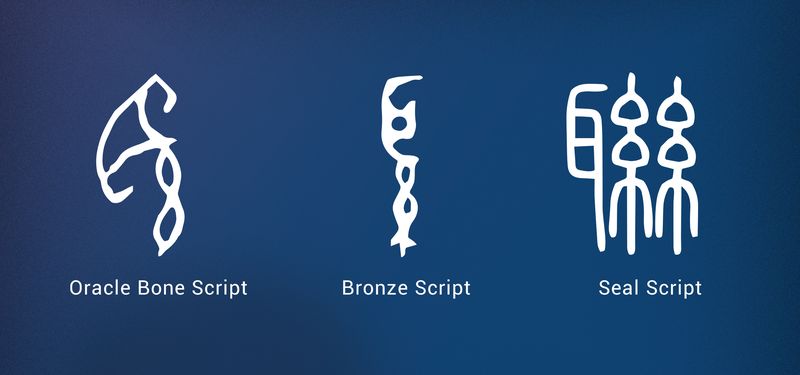

The Chinese character 联 (lián) first appeared in oracle bone script over 3,000 years ago. Comprised of an 耳 (ěr, ear) radical on the left and a 糸 (sī, silk) on the right, it symbolized tying something through a person’s ear, which scholars believe conveyed the meaning of “linking” or “joining.” Its current form emerged during the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), with the right part simplified as 关 (guān) in some texts, though its meaning has remained basically unchanged throughout history.

In Unofficial Gleanings of the Wanli Era ( 《万历野获编》 ), a Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) encyclopedia, scholar Shen Defu (沈德符) described people from Beijing going to the city’s suburbs to ”travel hand in hand, and prepare food and drinks on the ground (联袂嬉游,席地布饮 liánmèi xīyóu, xídì bùyǐn).”

Today, the phrase 联袂 (liánmèi, literally “join sleeves”) is mainly used in literary texts, while 联手 (liánshǒu, join hands) is more commonly used to express the idea of “going hand in hand,” as seen in expressions like 强强联手 (qiáng qiáng liánshǒu), meaning mutually beneficial cooperation.

The character’s meaning has since evolved to encompass various connections, close and far, physical and emotional. For instance, 联姻 (liányīn) signifies a connection through marriage, while 联盟 (liánméng) denotes an alliance. Just as 联姻 has been a means for rich and powerful families to enhance their wealth and status, businesses have shown a keen interest in 联名 (liánmíng), or co-branding, over the past few decades. This September, a collaborative product called “Fragrant Sauce Latte (酱香拿铁 jiàngxiāng nátiě),” launched by Kweichow Moutai, one of China’s best-known baijiu liquor producers, and coffee chain Luckin Coffee, sold over 5.4 million cups nationwide, generating revenue of 100 million yuan within one day.

联络 (liánluò) is to “contact” via phone or other means, and联络感情 (liánluò gǎnqíng) is to get in touch with the sole intention of building relationships. Many organizations have their own liaison department (联络部 liánluòbù), liaison office (联络处 liánluòchù), or liaison person (联络员 liánluòyuán). When an individual cannot be contacted, they are described as 失联 (shīlián).

Nowadays, the internet (互联网 hùliánwǎng) and other technologies have transformed the world into a “global village.” A message sent from Shanghai can be received within seconds by people in New York. With the help of social media, even public figures and celebrities are no longer distant—for better or worse. Popstars, journalists, and world leaders are all on Weibo or X, formerly known as Twitter, though their opinions and rants may not have made it easier for the United Nations (联合国 Liánhéguó) to achieve world peace.

Just as geopolitical alliances require partnerships to advance, Chinese rhyming couplets, or 对联 (duìlián), are only complete in pairs. People often paste these rhymes on either side of their door during the Lunar New Year, or other traditional occasions, with the messages commonly inviting good luck and prosperity for the family.

Another Lunar New Year tradition in China is to gather together, or 联欢 (liánhuān), with family and friends to celebrate. CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala, which it has broadcast every Lunar New Year’s Eve since 1983, even includes this term for “get-together” in its full name: 春节联欢晚会 (Chūnjié Liánhuān Wǎnhuì).

The Lunar New Year is a time of eating, celebrating, and, yes, money-giving. How else would people maintain their 社会关系 (social ties, shèhuì guānxi)?

On the Character: 联 is a story from our issue, “Online Odyssey.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.