In Zhao Song’s newly translated thriller, a recluse moves into a mysterious apartment block where not everything is as it seems

In the spring of 1989, I moved into a Japanese-style apartment building in the old part of town. I rented a single room on the first floor. There was a shared kitchen and bathroom. Not long after I moved in, the people living across the hall moved out. After that, the room sat vacant for a long time.

I appreciated the peace and quiet. I only had a single room and I never went across the hall, but I enjoyed feeling like I was the master of an expansive suite. The way I figured, if I was going to live alone, I might as well enjoy the solitude. If I needed someone around all the time, I’d go out and get married.

I’m a lazy person by nature. Back then, I spent most of my free time reading. I liked wuxia stories—martial arts masters descending into the underworld to seek revenge, that kind of thing—or collections of strange stories about ghosts and immortals. I wasn’t even above picking up the occasional gossip magazine. In order to preserve my indolence and give me enough time to read, I found a job as a night watchman guarding an engine room. My shift started at four o’clock every afternoon. Each day, I showed up with my book, dutifully took my post, and read until midnight, listening to the machines whirring behind me. Except for whoever came in to relieve me, I never had to deal with any coworkers. That was another perk of the job.

When I got home each night, I took a shower and cooked up some noodles or something else simple to fill my belly, then I would stretch out on my bed with a cup of tea and start reading again. I usually read until around four in the morning. Sometimes I would drift off to sleep with the lights still on. Sometimes I just didn’t feel like turning them off. Sometimes I even fell asleep with the TV on.

A middle-aged couple lived down the hall. We shared a wall. The husband was a brute. He liked to yell at his wife. Sometimes, she shrieked back at him. I was more or less used to it, though. The apartment across the hall from them—and so, down the hall from me—was being rented by a woman who was around 28 or 29. Come to think of it, she might have been even younger. She was a quiet woman, to the point of seeming removed from the rest of the world. You might be picturing her as elegant and aloof, but she actually seemed a bit eccentric to me. You know, there are some people who stand out because they are strange, but people can stand out for being too normal, too. Personally, I didn’t mind having an eccentric neighbor.

The night I met her, I had gotten home later than usual. I’d put in a half hour or so of overtime and taken a shower at work. Not long after I got home, I heard a knock at my door. I went to open the door with my coat still on. It was the woman from down the hall. You know, the quiet eccentric. She seemed a bit nervous. Instead of coming inside, she poked her head in and glanced around, then looked back at the closed door of the room across the hall. She had knocked because she wanted to know which room was mine. She seemed shocked that I wasn’t living in the room across from me, which shared a wall with her own.

I asked her what was going on. She hesitated for a moment, then said: “I thought you were living in the room next to mine. The last couple days, right around this time every night, I keep hearing someone knocking on the wall. I even heard someone singing.” I laughed and asked her if she was trying to spook me. That wasn’t the right thing to say. “You think I would come and knock on your door in the middle of the night just to mess with you?” she demanded.

I decided to take her more seriously. I turned on the light in the hall, motioned for her to come with me, but left my door open behind us. “Go knock on the door,” I told her, gesturing across the hall. “You can see for yourself if anybody’s in there.”

She hesitated. “You’re scared to knock?” I asked. “I’ll do it for you.” I stepped across the hall and rapped on the door. Just as I expected, nobody answered.

She walked back down the hall, but I could tell she wasn’t completely satisfied. “Sorry,” she mumbled reluctantly. “I should apologize for disturbing you.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I said. “I was still awake. You were probably just imagining things.”

She didn’t make any reply. The door slammed behind her. Standing alone in the hallway, I suddenly felt uneasy. I crept back to the closed door of the vacant room and put my ear against it. There was no sound coming from inside. It was so quiet in the building that I could hear the TV in the room above me. A half-deaf old man lived there with his mute son. I figured that must have been what she heard. That was my conclusion: She was working herself up over nothing. I could tell she was the type of girl who liked to give herself a fright. She was definitely a bit neurotic.

The next day, right around the same time, she knocked at my door again. This time, I was less patient. I stared at her coldly. She shifted awkwardly under my gaze, struggling with what she wanted to say, then finally blurted out, “I heard the same sounds again. The same as the night before. Exactly the same.” She begged me to come to her room, so I could hear for myself. She wanted me to know she wasn’t hallucinating. I considered for a moment, then followed her, closing my door behind me.

The young woman’s room was clean. There was a faint aroma in the air that I thought could have been perfume or cosmetics. From my own observations, though, she didn’t seem to be a woman who used either. Her room was mostly empty and simply furnished. The books were a surprise, though. She didn’t have a bookcase, but there was a stack of books on the floor, a pile on the desk, and even a few on the bed. Her tastes seemed quite peculiar, too. The pile on the floor was devoted to history, geography, and fortune telling. The stack on her desk was divided between astronomy, feng shui, and research into various paranormal phenomena. I noticed that some of the books were in English, including a six-volume set of Daniel Harrison’s Studies on Paranormal Activity in Ancient China. The binding on the set was so beautiful that I couldn’t stop myself from picking up one of the volumes and flipping through it. Of course, my English wasn’t any good, so I couldn’t read much more than the copyright page. I could make out when it was published, by whom, and who the editors were. The rest was incomprehensible.

The young woman was annoyed that I had gotten distracted by the books and seemed to have forgotten her problem. She cleared her throat loudly and pointed at the wall beside her bed. As I took a seat on her white duvet and surprisingly soft mattress, I once again noted a faint fragrance.

I listened closely. Silence. I glanced back at her. “I don’t hear it,” I said. She didn’t believe me and came over to listen, too. There was still no sound.

She looked disappointed, thought for a moment and said, “Maybe it’s done for the night.”

“Fine,” I said. “You want me to come back tomorrow?” She had no choice but to agree.

As I left, I took another look at her books. I told her she had decent taste. Some of the books looked rare. “But don’t read too much of that stuff,” I warned her. “It puts ideas in your head.”

She shot me a dirty look. “You mean reading those books is causing me to imagine all of this?” she asked.

I waved her off. “It’s just a suggestion,” I said.

“Well, thanks, I guess,” she said.

“Don’t mention it,” I said. “After all, what are neighbors for?” I could tell she didn’t find that funny. That woman didn’t have much of a sense of humor.

The next day, I went to her place as soon as I got off work, bringing a few tangerines that I picked up in the night market. They weren’t intended as a gift. I just happened to have some extra. When we got into her room and stood under the light, I noticed that she seemed to be wearing makeup. It gave her a sultry air. She was smoking, too. I hadn’t expected that. There were no signs of it the day before. She held a finger to her lips, signaling me to keep quiet. We pressed our ears to the wall and listened in silence. I realized she had been telling the truth. The sound couldn’t be coming from upstairs. It had to be from the next room over.

At first, it was a slow, rhythmic knocking. It reminded me of monks striking a wooden fish to keep time during their chanting. The rhythm almost matched, but the sound was less sharp. After that came the sound of singing, or more accurately, chanting. Again, it reminded me of monks reciting sutras, but the syllables were clearer. It almost sounded like someone muttering, mixing in the occasional grunt. The voice was too muffled for me to make out what it was saying. I was a bit freaked out, and realized that I had broken out in a cold sweat. My palms were clammy. When I glanced back at the young woman, I instantly felt very close to her. There’s a saying that fear has the power to bring complete strangers together as intimate friends. I think it’s spot on.

She poured me a cup of hot water and set it on the coffee table beside her bed. I stood for a moment, slightly stunned. I ended up pacing nervously around the room. “You believe me now?” she asked. She was sitting on the sofa, looking calm.

“Yes,” I said. “I’ve never heard those sounds before.” I realized that I probably sounded like a wimp. I felt embarrassed.

“Are you scared?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, “a little.”

“So, what should we do?” she pressed.

I told her that we should wait until tomorrow and ask the landlord for the keys to the room. That was the only way to know what was going on in there. She agreed. But she was worried we wouldn’t be able to get to the bottom of the matter just by doing that. “What I’m worried about,” she said, “is that it’s not somebody or something, but…”

“You think it’s haunted?” I asked.

She paused, as if reluctant to admit the possibility. “Do you believe in ghosts?” she countered.

“Ghosts could be real,” I said, “or it could be all in people’s heads.” That had always been my way of thinking. I had no evidence one way or the other. “But it doesn’t matter what I think. I don’t have any experience with supernatural stuff.”

“Now you have,” she said with a smile.

“Are you tired?” I asked.

She shook her head. “I was sleepy during the day. I even dozed off around noon. Now, I’m not tired at all.”

I wasn’t tired, either, so I took out the bag of tangerines. I gave her the biggest one, peeled one of the tinier ones for myself, and ate it in a few bites. They were seedless, and very sweet. I watched as she gently kneaded her tangerine, rolling it around in her hands. After a while, she dug her thumbnail into the top of it. One by one, she methodically squeezed each segment up through the hole and ate them. She took her time. I could tell that she was a very patient person.

It was only natural that we started making small talk. She told me that after finishing university in the provincial capital, she had gotten a job here as a librarian. Her major was history. Her hobby was researching the I Ching. I couldn’t help but admire her. I immediately blurted out that I used to like reading the I Ching, too. The book was intended for fortune telling, but I liked to read its statements as poetry.

“Those statements aren’t important,” she smiled, shaking her head.

“Why not?” I asked. I didn’t appreciate her directness.

She went on, as if talking to herself: “What’s really important is the numbers. You know what I mean? It’s the numbers behind the statements. Invisible numbers. Not the text. If you can understand those, you can tell the future, and know the past too. You can easily comprehend all events from all times. Just like Song dynasty philosopher Shao Yong, once you understand the I Ching, you can come up with your own model to predict things with.”

She really knows her stuff, I thought to myself.

“Did you know Confucius once warned people about the I Ching? He said it was okay for playing around, but if you got too deep into it, it would cause you problems. Spotting fish in a deep pond is not auspicious, as the saying goes. There’s such a thing as knowing too much.”

The bag of tangerines was gone before I knew it. From the light coming through the crack in her curtains, I could tell that it was probably dawn. Without realizing it, we talked until five-thirty in the morning. I slowly shook off the spell she had cast as she talked about the I Ching through the night. I breathed a sigh of relief, and said goodnight to her. When I got back to my room, I crawled into bed and slept soundly.

We became friends. It was only natural. We both liked books. I was not reading at her level, but that wasn’t a problem. She was a good teacher and I was a keen student. As for the strange sounds coming from the neighboring room, they continued for about a week and then stopped. That perplexed my new friend. She eventually decided to use the I Ching to divine for an answer. She rarely used the I Ching for divination, but she decided to make an exception. After consulting the book, her conclusion was that the room had been inhabited by a spirit that was stuck in the living realm, and had been practicing self-cultivation in order to move on to the next life. Only two weeks had gone by in our world, but for the spirit, it had been equivalent to two hundred years.

That all sounded slightly far-fetched to me. I had never come across this form of divination in any books about the I Ching, but I nodded along and took things with a grain of salt. Whatever or whoever had caused it, the sound was gone. I didn’t need to worry about being kept up by the creepy goings-on across the hall, and, if I went over to chat in her room, we weren’t going to be spooked by strange sounds from next door.

I was always curious about her English books about the ancient Chinese paranormal. It turned out she had not read them. They were mailed to her by a former classmate who had moved to the UK. They were accompanied by a letter that said that they’d been taken from an old monastery in London and were allegedly left behind by a young monk. After explaining this, she picked up one of the books, flipped to the last page and showed me a signature in flowing, cursive writing. I picked up another book and discovered the same signature. I flipped through the book and stopped on a page with a woodblock print of a cat lying under a poplar tree that was shedding its leaves. I turned the page and handed the book to her. “Can you translate it for me?” I asked. “Just give me a rough idea, at least.”

She took the book, carefully read the passage, and then summarized it for me: “In the Song dynasty, there was a monk. He had a cat that lived in the temple with him. He didn’t pay much attention to it. The cat used to recline beside the sutra hall and listen to the chanting. The monk eventually developed some kind of skin disease. It was contagious, so the other monks left the temple. He had only the cat to keep him company. The disease got worse. Nothing he tried seemed to improve the condition. One day, the cat came to him with a scrap of paper in its mouth. It was a torn-off page from an ancient book. When the monk looked closer, he saw that it was a prescription. He saw that the symptoms it listed were identical to his own illness. The recipe was simple: burn some cat skin and rub the ashes on the affected area. The monk sighed and looked down at the cat. It stared back at him. He told the cat to leave. His illness was none of its business. The cat didn’t move. The monk asked why it wouldn’t leave. And the cat actually answered. It had a human voice. ‘Diamond is impenetrable,’ it said. The monk had always recited the Diamond Sutra, so that’s what the cat had to be talking about. At that moment, the monk achieved enlightenment. He left the temple. The cat was left alone.”

“What does ‘diamond is impenetrable’ mean?”

She studied the ceiling, not speaking for a moment. “That’s my question, too,” she said.

“It makes no sense to me,” I admitted. I had no knowledge of Buddhism, so I was out of my depth.

She wasn’t put off by my cluelessness. She thought this story might not have been a supernatural tale, but a Zen koan. I wanted to know what the difference was. What counted as paranormal activity? She told me that it was simple. Once we figured out the source of the mysterious sounds from next door, then that would count.

“I thought you already consulted the I Ching,” I said.

“You can’t only go off the fortune I got,” she said with a smile. “It won’t match up exactly with what really happened.”

“Are you scared?” I asked her.

“Of course,” she said. “I’m only human. We’re dealing with something from another realm. Of course I’m scared.”

“Me too,” I said. I tried my best to sound casual: “But whatever. If he comes again, we’ll deal with him.”

She said nothing but smiled grimly.

The next day, I slept until noon. I was awoken by a knock at the door. When I opened it, I saw the guy who lived next door to me. He studied me quizzically. “Why were you knocking on the wall last night?” I had no idea what he meant.

“When was this?” I asked. He told me the time. It was about the same time of night when the young woman and I had usually heard the sounds from the room across the hall. But at that time last night, I had been in the young woman’s room. I told him that I had a witness who could prove I wasn’t making the sound.

“A witness?” he asked. I smirked and led him down the hall. When he saw me going to knock on the young woman’s door, he was even more mystified. “Hey,” he called, “are you sure you’re awake?”

“Fully awake, my brother,” I said, knocking again on the door.

“That room is empty,” he said, giving me a tap on the shoulder. “You realize that, right?”

Impossible! I kept knocking. She just wasn’t home, I concluded. I turned back to the man and said, “Wait until she gets back tonight. She must be out.” Confused and annoyed, he went back across the hall, muttering to himself, and slammed the door behind him. That night, I knocked again at her door. There was still no answer.

A couple days later, I was awoken at noon again by a sound in the hallway. When I looked out, I saw that somebody was moving in. The door to the young woman’s room was open, and several people were tidying up inside. “Did that girl move out?” I asked one of them at random.

“Who?” the man asked, puzzled. “I just moved in.”

“What about the girl who was renting this room?” I asked.

He shook his head. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said. When I stepped into the room, I was even more surprised: instead of books piled against the walls, there were slabs of stone covered with old newspaper, and on the desk were a few pieces of mismatched wood with scraps from old English newspapers pasted on them. The bed had been stripped of its white duvet and sheet.

As I was looking around, an old woman came to chat with the new tenant. I overheard her saying that it was good he had moved in, since the place hadn’t been rented out in months. That made it much easier to clean up, too. She noticed me and asked, “You’re the fellow that lives across the hall, aren’t you?” I explained that I lived one door down. “Is that room across from you still empty?” she asked. “You wouldn’t remember, but there was a girl who lived there for a while. She got a rare skin disease and passed away from it very quickly. It was a real shame. She was a sweet girl, kept to herself...A shame for the landlord, too, since he can’t find anybody willing to rent that room.”

The new tenant seemed shocked to hear all of this. “What kind of stuff goes on around here?” he asked.

Right, I thought to myself, feeling the panic rising. I suppose this is the kind of stuff that goes on around here. I felt a shiver run up my spine.

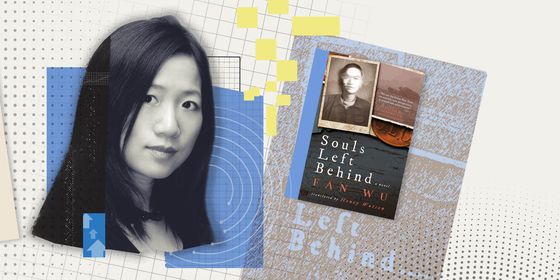

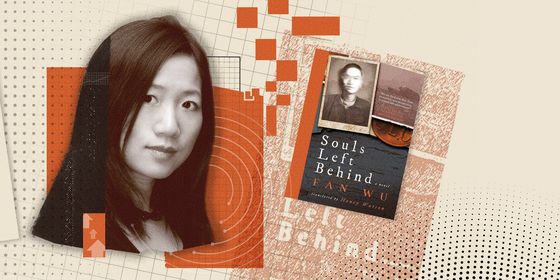

Author’s Note: My inspiration for “Neighbor” came from stray cats always showing up at my window before Halloween, as well as the work of the great Argentine short-story writer Jorge Luis Borges. This story reminds me of how surprisingly imaginative improvised writing can be—it’s like a random strike, but worth keeping in mind. Now I always try to make room in my work for improvisation and fun, which may be the most important thing when writing.

Neighbor | Fiction is a story from our issue, “Public Affairs.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.