The growth of cellphone addiction among China’s “left-behind” children and the researchers and teachers fighting against it

Xia Zhuzhi only lets his 6-year-old daughter use the internet for 30 minutes a day. “Kids can’t let go of their cellphones,” says the 36-year-old associate professor from Wuhan University. “Childhood shouldn’t be about squatting in a corner scrolling through a phone all day.”

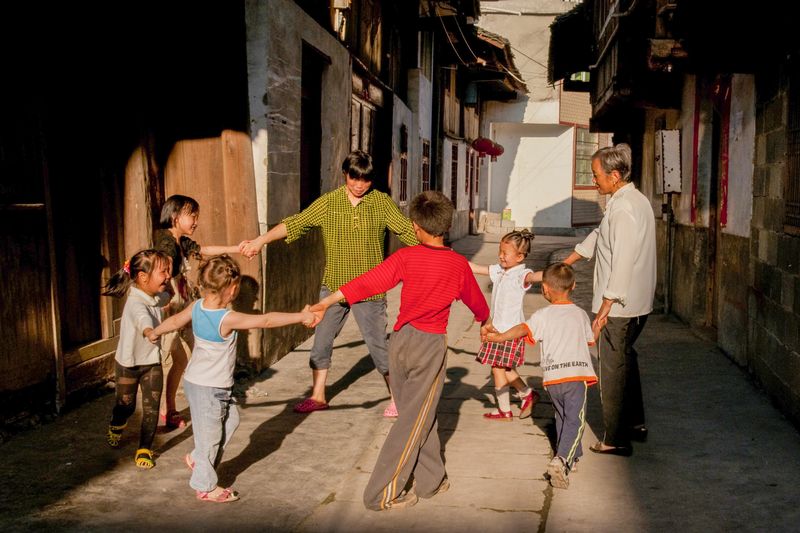

Many other parents aren’t so strict. During the Spring Festival holiday this January, Xia visited his relatives in rural Huangshi, Hubei province, but found that their pre-teen son rarely emerged from his bedroom. He was engrossed in his phone all day and refused to even greet Xia. “That’s no childhood,” says Xia. “Childhood should be about finding playmates to share fun times, and experiencing happiness and sadness together.”

Since September 2021, Xia and 149 other researchers from Wuhan University have visited nine rural counties in Henan, Hubei, and Jiangxi provinces to explore a phenomenon sweeping the countryside—cellphone addiction.

They found rural minors, especially the country’s 12 million “left-behind” children whose parents have moved away to work in distant cities, are spending most of their spare time indulging in short videos and mobile games without adequate supervision from their caregiver (often grandparents).

After surveying more than 1,000 households each year, the researchers found that cellphone addiction has profoundly impacted the physical and mental well-being of children, from their academic achievements to their daily lives and even family bonds. Many families and schools are at a loss with how to deal with children glued to their phone screens.

A report published this January by the China Rural Governance Research Center at Wuhan University, which Xia helped write, found that over two-thirds of 13,172 parents thought their left-behind children had a tendency toward cellphone addiction, while over a fifth reported that their children were already seriously addicted. Over 40 percent reported their child had their own cellphone, while half of them said their child used a grandparent’s device.

“There are few children playing and enjoying themselves in rural areas,” Xia tells TWOC. When Xia and his research team visited Yangxin county, Hubei province, they didn’t see any children on the way until they reached the hotel—two boys and one girl, around seven years old, all engrossed in a short-video platform on a cellphone in the hotel lobby. “Even during school breaks, classrooms and playgrounds are eerily quiet. Rather than play outside, children, especially boys aged between 8 and 14, prefer spending time watching short videos and playing video games. The social realm of rural children is swiftly shifting from nature to virtual space,” explains Xia.

Li Huanhuan, a 22-year-old teacher in rural Chenzhou, Hunan province, is constantly checking whether her students have brought their phones to class. All the 40-plus students (most of them left-behind children) in her middle school class have their own mobile phones and WeChat accounts. “The boys play video games and watch short videos, while the girls take photos,” Li, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym, tells TWOC.

When Li visits children at home, she finds “some students are quite introverted. They don’t know how to communicate with teachers…They don’t say anything but just bow their heads and play on their phones.” Judging by the frequency they post updates on their WeChat social feeds (or “Moments”), some students spend their entire day online.

One of Li’s students even had to drop out and was sent to an internet addiction center for a year after he began spending entire days on his phone in bed. An elementary school teacher in a county in Jiangxi told Xia and his team that more than half of their students spend over 10 hours glued to their cellphones on weekends.

Elementary and middle school students are at higher risk of cellphone addiction, Xia says, because they have more free time than high schoolers who have longer school days, shorter holidays, and typically better supervision.

“Left-behind children have no one to supervise them, so they of course turn to cellphones. Once-popular activities like rope skipping, playing basketball, and going fishing have all disappeared in rural areas. Now, smartphones have become everything. They’re incredibly convenient and affordable,” Xia tells TWOC.

In Xia’s own school days in Huangshi in the 1990s, he had to walk over 10 kilometers to attend classes. In that era without smartphones and computers, his spare time was filled with picking wild fruits in the mountains, climbing trees to find bird nests, fishing in rivers, and playing with rubber bands.

When Xia visited Huangshi for research in 2021, however, children told him a different story. Among the more than 30 students in one elementary school class, only one did not have their own cellphone. Some students were even aware of the problem, according to Xia: “They said ‘What else can I do if I don’t play on my phone?’ and ‘I don’t want to be addicted, but I can’t help myself anymore.’”

The grandparents who often care for left-behind children can be extremely cautious about the children going out to play, fearing they will get into fights, drown, play with fire, or even fall from trees. “[Grandparents and parents] are afraid that kids are not safe outside the house,” says teacher Li. “In the past, nobody cared whether kids played outside, but now they are told to go directly home after school and stay at home, where they watch TV or play on their cellphones.”

Smartphones have become “digital babysitters” while grandparents go out to farm, work, or meet their own friends for leisure. “[Grandparents] have limited energy but must look after the children’s daily needs, including food, clothing, and shelter,” Liu Qi, who has worked as a teacher in a village in Xihua county, Henan province, for over 20 years, told Southern People Weekly magazine this March. “It’s very challenging for them to handle the child’s education. When children cry or throw tantrums, they might hand them a smartphone to at least give themselves some freedom and a temporary break.”

Xia and his research team also found that cellphones were blamed for the deteriorating physical health of students and the upsurge in crime. Many teachers Xia talked to attributed poor eyesight and even vision loss among students to the amount of time they spent on their phones. Additionally, Xia’s research team learned from the local law enforcement authorities in a city in southwestern Hubei, that around 70 percent of cases involving sexual assault of minors in the city during the first half of 2021 were linked to online dating or gaming. According to local officials, the number of such cases involving minors during that period surpassed the total cases reported in three years from 2017 to 2019.

Authorities have sought to address the growing addiction problem. In 2021, the Ministry of Education prohibited all elementary and middle school students nationwide from bringing cellphones into schools. If they must bring a phone, students need written permission from their parents, and even then, cellphones are banned from classrooms.

In 2021, the National Radio and Television Administration restricted minors to one hour of video games on weekends. “But some children have found ways around these measures by using the ID cards and photos of their grandparents to access games or watch videos. The older generations don’t understand [what they’re being used for]…There are a lot of ways for them to play games still,” says Xia.

Rural schools also struggle to prevent students from bringing their cellphones to class. At one middle school in Yangxin, students must pass through a metal detector at the school gates. But the children devised various strategies to bypass this, such as concealing their phones in the soles of their shoes, or having others pass them phones from outside the school walls. Another secondary school in Yangxin spent over 500,000 yuan in 2020 hiring retired soldiers to patrol school grounds and confiscate phones.

Jin Yu, a village teacher in Shaanxi province, tells TWOC that left-behind children often persuade their grandparents to let them use their phones. “To avoid that, we tell their parents [or guardians] that we will never send homework or online courses via cellphone and ask them not to give their kids phones,” she says. “For those who still get phones, teachers will visit their homes to discuss with their guardians before collecting the cellphones, and only return them during vacation,” says Jin.

Xia agrees that the most effective approach is to keep smartphones away from children. “Instead, a simple smart watch for communication purposes would suffice. It’s also wise not to grant children unrestricted access to the internet but rather impose limits,” says Xia.

It isn’t always that straightforward. “Whenever I take away my granddaughter’s phone, her mother would buy her a new one,” Li Cuinian from Jiangxi told Southern People Weekly in March. Li Cuinian said her daughter-in-law has bought the child six cellphones in recent times because she keeps confiscating them.

According to teacher Li Huanhuan, addiction drives students to extreme lengths to get their phones back. Last year, a grade nine student (who would have been 15 or 16 years old) fell on his knees in the school principal’s office begging for him to return his confiscated phone and threatening to drown himself if he didn’t get it back.

“We can’t just ban them from using phones altogether. Lots of stuff needs to be done online, like signing up for some exams and checking their remarks,” says teacher Li. “If you don’t have a phone, you need to borrow from others, but often you can only have one account [linked to one phone number],” she explains.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, schools across the country offered online classes for long periods. “Some students asked their parents to buy phones for them [to study], but after class they would just play on their phones, especially now that there are fewer online classes,” says Li Huanhuan.

This January, Xia invited several children from his village in Huangshi on a hiking trip to get them off their phones. These children, who used to spend their entire day on their phones, walked over 20,000 steps almost without a single glance at a phone screen, Xia claims. “By actively diverting their attention, we helped them develop a new habit. They realized that it wasn’t essential to constantly be on their phones. They discovered the joy of playing outside...They can now choose to use their phones or not.”

Concerned about the rising phone addiction among children in their hometown Huanggangmiao village in Hubei, retired teacher Lei Xuxin and his son Lei Yu, a journalist in his 30s, together with the local government, established a community center called Hope Bookhouse this March. The center is designed for students from grades two to six, providing a space where they can study, socialize, and play with volunteers.

“It’s sad for me to see these left-behind children spending entire days playing mobile games,” Lei Xuxin told state broadcaster CCTV this October, explaining his motivations. “These kids in my hometown often squat under the roofs of the homes with Wi-Fi and play on their phones.”

Located in Sanlifan town, where 90 percent of household revenue comes from people working outside, the village has 600 permanent residents, most of them elderly or children. One principal at a high school in the town told Xia that many students’ academic performance, and even their morality, were slipping due to their addiction to cellphones. The children rarely used their phones for study, according to the principal.

The Hope Bookhouse project in Huanggangmiao is based inside a renovated government building, and provided free reading, calligraphy, and chess classes, as well as significant outdoor play time, to over 40 pupils this July. The children quickly forgot about their phones when they played together, according to Xia, who participated in the establishment of the center. “The kids got familiar with each other, connected with the entire village, and finally began relishing their childhood,” he says.

Xia is planning to set up a similar center for about 40 children in Huangshi. He has already transformed two rooms of a local primary school in his hometown with books, desks, and other non-digital activities. Five teachers have signed up to entertain children during the summer vacation next July.

Xia hopes he can convince the children of the virtues of the non-digital world, get them to ditch their cellphones, and spend more time playing outside like he did when he was young. “Children should be able to find the meaning of their childhood [outside],” he says.

Digital Babysitters: Battling Phone Addiction in China’s Rural Schools is a story from our issue, “Online Odyssey.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.