Facing more bureaucratic formalities, overwork, and dwindling respect, many of China’s teachers are leaving the profession for good

Warning: This piece contains references to suicide.

Two years after getting a master’s degree in Chinese education, Xiao Yu resigned for the second time. Having taught for two years, first in a private school and then a public one, she has lost faith in the profession she’d dreamed of pursuing since her school days.

Instead of the meaningful job she imagined where she could “impart knowledge and educate people,” Xiao found the majority of her work irrelevant and meaningless: meetings, events, and writing up reports mainly for promotions and government inspections, even occasionally doing the job of government agencies. Several times, she had to stand at the school gate and check that parents dropping off their children by scooter were wearing helmets, as requested by the local traffic bureau. “If some parents are found without a helmet, the student’s homeroom teacher would be blamed for not ‘educating’ the students and their parents well,” she tells TWOC several months after she resigned from her second school in September 2023.

Amid all these other demands, actually teaching was something Xiao had to “squeeze time for.” The 27-year-old from Chengdu, Sichuan province, tells TWOC that it was only after 6 p.m. each day, when all her students had left, that she had time to prepare the next day’s lessons (assuming there were no meetings to attend). Course preparation took another hour, during which she might also be fielding the parents’ questions and complaints over the messaging app WeChat—sometimes continuing at home, until midnight.

China’s high-pressure educational system may be famously difficult for students, but stress and depression among elementary and secondary school teachers are becoming a serious concern. On the social media app Xiaohongshu, where Xiao has a mere 200 followers, a post from her explaining why she chose to resign attracted “likes” and outpourings of sympathy from thousands of viewers.

Others have faced worse fates. In October last year, a 23-year-old homeroom teacher, surnamed Lü, jumped to her death from a building after just two months on the job. “I feel like I can’t breathe. I never thought being an elementary school teacher would be this hard,” she said in a suicide note addressed to her family on her phone.

Lü’s family members told journalists she had often complained about having to work seven days a week, performing pointless tasks, and being humiliated and verbally abused by her superiors. “I really aspire to teach and educate the pupils well, but the school’s assignments, events, inspections…have trapped newly qualified homeroom teachers in a cage with increasingly shrinking space,” she wrote in her note. “When can teachers focus on teaching and education? How can unhappy teachers cultivate positive and optimistic children?”

Teachers’ changing role

As one of the most famous teachers in Chinese history, Confucius is credited with saying, “Only if teachers are respected will knowledge be respected.” Historically one of the most revered professions in Chinese society, teaching has added cachet in the modern day because it is one of the few “iron bowls”—state sector jobs with guaranteed lifetime employment, and other benefits like housing subsidies—remaining after China transitioned to a market economy in the 1980s.

But contrary to the popular belief that teachers enjoy job stability and long vacations for just a few hours of lecturing each day, a survey, jointly conducted by state media outlet Guangming Daily and the National Institute of Education in November, showed that in 12 cities and provinces, 92.1 percent of the teachers surveyed worked over 9 hours per day, and over one-third worked more than 55 hours per week. This is 11 hours longer than the maximum 44 hours stipulated by China’s Labor Law.

Wang Xia, an elementary school teacher from China’s Inner Mongolia region, partially blames the increased burden on teachers and students on the growing competitiveness in education, starting as early as elementary school. “Back in my elementary school days, we had a lot of time to play, but now parents and teachers would worry the kids cannot get into a [good] middle school, and then a [good] high school [and then college]…” says the 30-year-old, who has been a Chinese language teacher since she graduated from college in 2018.

Reforms to the national curriculum in recent years, introducing more difficulty in academic subjects, have also made things harder for both teachers and students. To make sure students succeed in exams, a boarding high school in the southwestern Guizhou province schedules lessons and study time for students from 6:20 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. Monday to Friday, as well as all morning on Saturday. “[The school] tries to make use of every minute…To relax for one moment is seen as being careless about students’ future,” says Ma Ruyi, a former English teacher at the school.

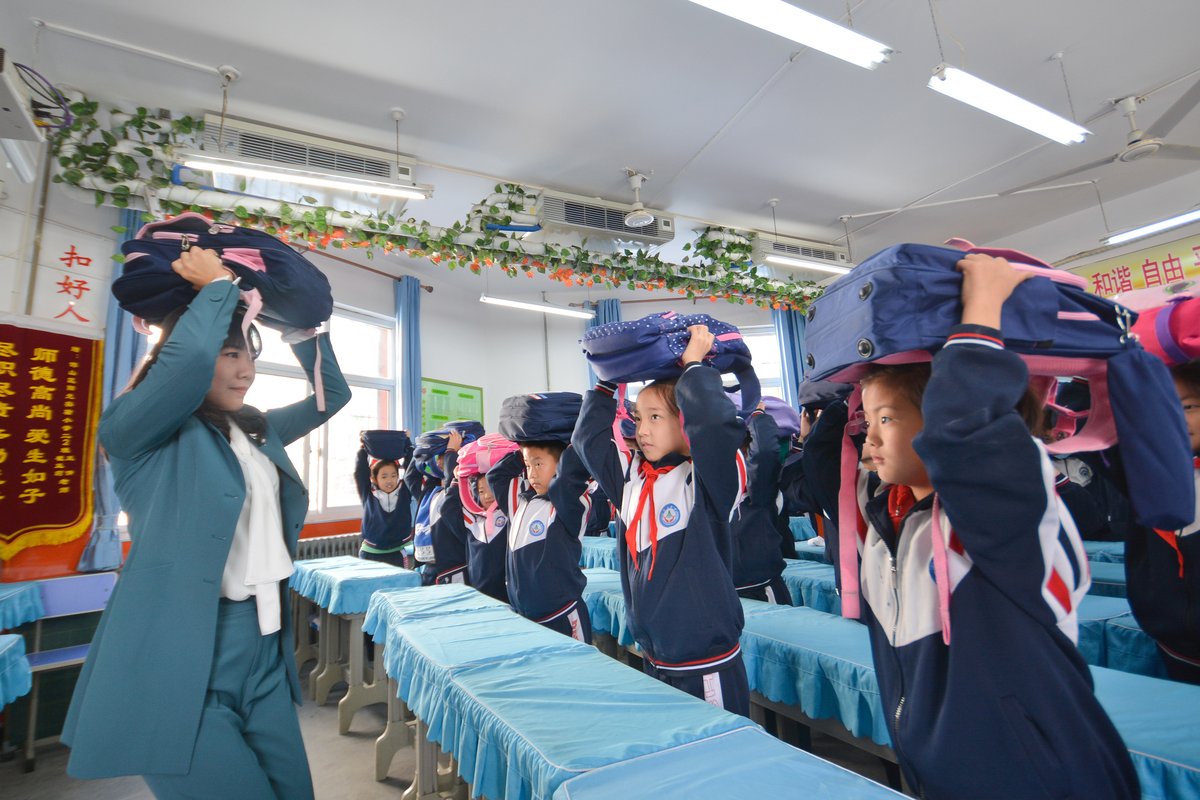

Whatever time is left over from studies is dedicated to events and activities for the school’s branding and rankings, in accordance with Chinese authorities’ efforts to promote “well-rounded” education in the last decade. At Ma’s school, there was an art festival, sports meet, or basketball competition every month, which teachers had to prepare for outside of lesson-planning time. For homeroom teachers like Wang, who manage the affairs of the whole class in addition to teaching their subject, the workload is significant. “A homeroom teacher must be omnipotent,” she says.

Since the central government introduced the “double reduction” policy in July 2021, which curtailed or banned after-school tutoring at the elementary and middle school levels in an attempt to reduce the academic pressure on young children, school hours in some cities have been extended up to two hours. The so-called “after-class services” stretch on until 5:30 or 6:30 p.m., with teachers reporting having to work until midnight after a 10-hour workday or on weekends to prepare lessons and correct students’ homework.

Too busy to teach

However, extra teaching hours are not the core of most of these teachers’ complaints. Instead, they believe the bureaucratic formalities and the other non-academic duties of their job are their main source of pressure.

Hua Jing, an elementary school teacher with 13 years of experience from Hunan province, thinks these non-academic duties have been on the rise. “Before, it was mostly about teaching, including lesson preparation, marking students’ exercise and homework, and after-class tutoring…but now we’re like maids,” she says.

Hua cannot pinpoint when things started to change, but asserts the extra work takes a significant toll. One dreaded task is the need to keep a record of almost everything that happens during her job to present during the next official inspection. Each semester, she keeps a dozen written journals, which record notes of school administrators’ speeches during weekly staff meetings, insights she got from online and offline training, thoughts and reflections about her own and colleagues’ lessons, records of multimedia tool usage for each lesson, her teaching plans and objectives, the analysis of her students’ final exams, and more.

Hua has also been asked to collect students’ medical insurance payments from their parents; ask parents to watch anti-drug and other public lectures or videos online; and to download certain apps, follow certain social media accounts, and “like” certain posts online to appease some government departments or even school officials’ friends and acquaintances. She has even had to write out teaching plans by hand for inspectors to read.

In May 2022, a viral article titled “Only the Bureau of Animal Husbandry Has Not Given Teachers Assignments” summarized dozens of other non-academic tasks that various government departments have asked public school teachers to perform, including publicizing poverty alleviation campaigns, anti-fraud and anti-drug education, fire safety and water safety education, and publicizing traffic rules.

“Many government departments believe that parents will be more cooperative if teachers are involved, as their children are in our ‘control,’” Hua reasons. Ordinary teachers can hardly refuse, as the fulfillment of these tasks is taken into account in their performance evaluations, which in turn can affect their chances for promotions and raises.

Expecting teachers to be on-call 24 hours a day has become an unfortunate trend, especially with the rise of messaging apps that make it easy for parents and school administrators to reach teachers anytime, any place. Tian Rui, a mathematics teacher and homeroom teacher at an elementary school from another city in Hunan province, says she gets nervous when seeing new message notifications in the school’s WeChat groups—usually announcing meetings, inspections, and other assignments, and often appearing in the evening. On the one hand, she doesn’t want to miss important notices; on the other, receiving the message usually means working overtime.

Authorities have taken measures to reduce teachers’ burden, but to little effect. In December 2019, the Communist Party’s Central Committee and China’s State Council jointly issued guidelines to reduce school teachers’ burden, including cutting down inspections and social tasks at school by at least 50 percent. However, in 2021, Chengdu educator Li Zhenxi carried out a survey on his public WeChat account where most of over 6,000 teachers said that inspections and social tasks occupied over 90 percent of their non-teaching hours at work.

Where’s the respect?

Along with the increasing workload and pressure, many teachers feel that Chinese society no longer respects teachers the way it used to.

Xiao thinks that her old job was less about teaching and more about being a “nanny” to a class of first-graders. She was responsible for students’ well-being not only during class, but also recess and lunchtime. “Almost every evening, I had to reply to parents on WeChat asking me to change their kid’s seat, what to do if the kid forgot their textbook at school, or complaining why I didn’t make sure their kid drank water because their water bottle was still full,’” she tells TWOC.

Compared to the past, parents today are more aware of their rights, and some take it too far by complaining to school authorities about trivial matters, Xiao believes. Once, a parent shouted at her and insulted her education level because she thought Xiao didn’t inform her quickly enough when her daughter hurt her teeth while horsing around with another student. “You can feel they hold little respect for you,” Xiao says.

She also feels the school doesn’t take the teacher’s side when parents complain, as they’re concerned the parents may take up the issue with the authorities or publicize it online, which will impact their reputation.

Xiao eventually resigned, citing health issues such as cysts on her thyroid, breasts, and ovaries—symptoms typically associated with stress. Ma, the former English teacher at a boarding school, also left the job last year to work in an office after she found that she was falling sick more often; some of her colleagues even developed heart conditions, she claims. “I felt like a zombie, with little patience and feeling tired and sleepy all the time,” she says.

From Xiao’s point of view, even teacher Lü’s death has not attracted much attention among the general public, but only among the community of teachers. She has started a WeChat support group which 200 teachers have joined. For some of them, the tragedy has just brought on more burdens at work. In the comment area under Xiao’s Xiaohongshu post about this case, and two similar teacher suicides last year, one teacher wrote, “Now we need to hand in a report on our mental health every week.”

Hua, the teacher with 13 years of experience, says she still likes the work and decided to “lie flat”—giving up competing for honors and promotions, but concentrating on teaching and tasks she absolutely cannot avoid. “It’s too tiring and meaningless…it’s not worth it just for several hundred yuan [in pay raises],” she says. After all, she figures, she already has job security for life.

The names of the teachers in this piece have been changed to protect their privacy.

No Time to Teach is a story from our issue, “Education Nation.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.