Once dismissed as a pastime for dropouts and gangs, pool has clawed its way back to become a booming pursuit among amateurs and professionals alike, driven by social media, grassroots clubs, and national campaigns

By the time Yan Qin finally stepped into a pool hall last April, the marketing graduate expected to find little more than a smoky room full of men with bleached-blond hair chewing betel nut under neon lights.

“Every time I passed one, it looked grimy and noisy,” recalls the 23-year-old from Changsha, Hunan province. But one night, after being invited by her friends, Yan played for eight hours straight, spending around 20 yuan per hour. “Once you pocket a ball, you get this strange, simple joy,” says Yan. “Not everyone was there just to pose. Some were real fans, and they played seriously.”

Yan is part of a growing wave of young Chinese people rediscovering the joy of cue sports. For decades, playing pool has mostly been the pursuit of men and stigmatized because of its association with gambling, gangs, and dropouts. But attitudes are changing. China now boasts an estimated 210 million hobbyists—a figure growing at 180 percent a year. Everyone from school kids to retirees is packing into pool halls, fueled by China’s growing success on the world stage and pool’s casual, low-pressure stakes and social appeal.

Explore today’s youth culture trends in China:

- As the “2D Goods Economy” Explodes in China, Can Fantasy Worlds Solve Real-life Woes?

- Youthful Nostalgia: Why China’s Gen Z Is Embracing the Past?

- Can Young Chinese Sustain Their Newfound Rural Life by Simply Farming the Land?

This recent resurgence is breathing new life into the industry. According to research firm iiMedia, China’s pool industry is worth over 87 billion yuan and is expected to exceed 192 billion yuan by 2030. More than 110,000 new billiard-related businesses were established in the first 10 months of 2024. Among them, hanging out in 24-hour self-service pool halls in malls and other public spaces has become a new craze nationwide for millions of young urbanites craving a way to unwind. “It’s like playing scratch cards,” Yan tells TWOC. “You might aim for one pocket, but sometimes the ball drops somewhere else. You have to stay sharp and adapt. There’s a little strategy, a little luck—and that’s what makes it fun.”

Yet behind its rising popularity, players and coaches are working to challenge deep-rooted stereotypes and earn the game recognition as a respected, disciplined sport.

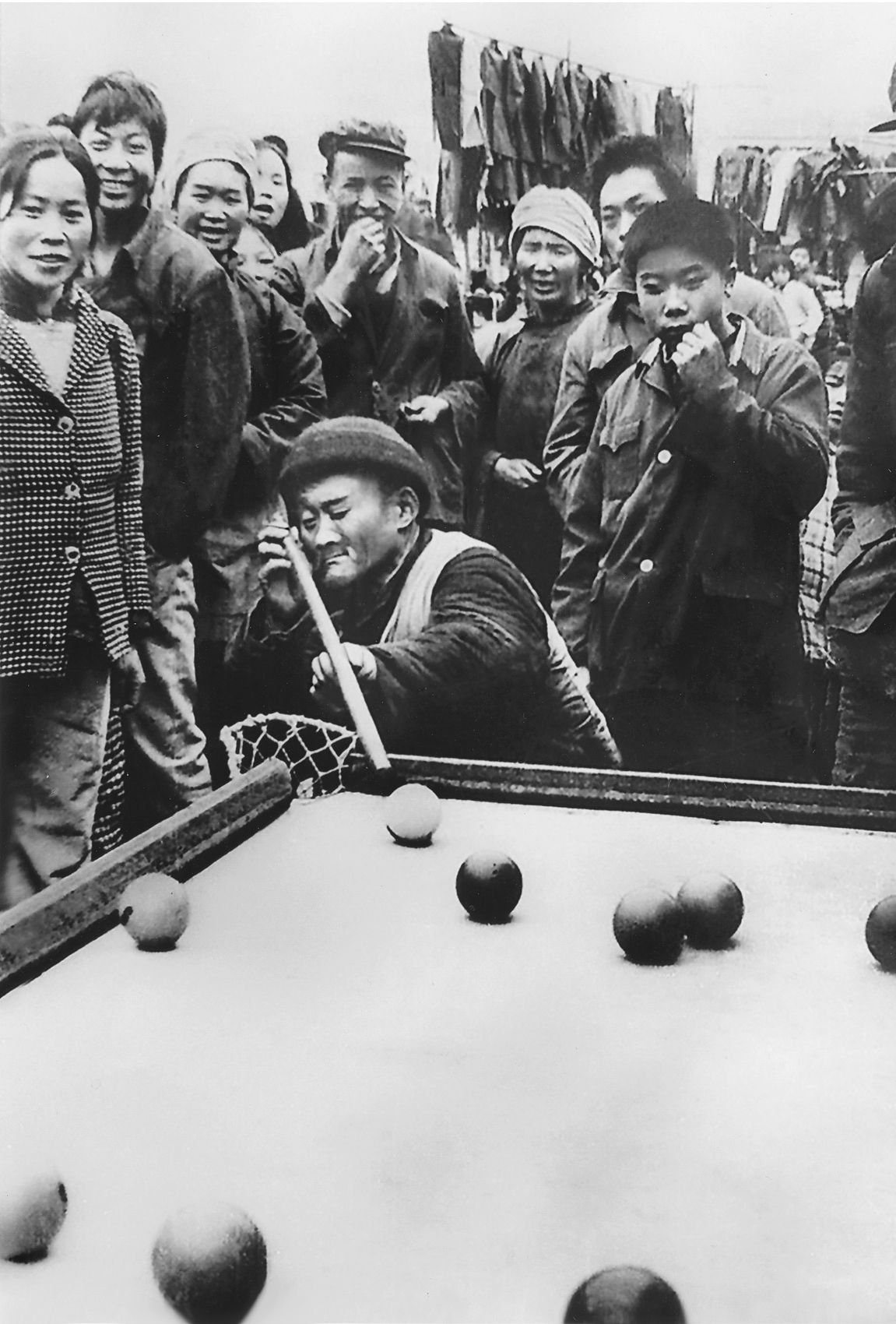

The stigma around pool didn’t always exist. Pool, initially referred to as da danzi (打弹子), first arrived in China in the late 19th century and was accessible only within the foreign concessions at the time. Then, in the 1980s, Chinese pool, a hybrid of American pool nd snooker, with simplified rules and smaller pockets, gradually took over street corners and small-town halls. An article from People’s Daily in 1988 noted that in a stretch of less than 10 kilometers, there are over 200 pool tables set up along the streets. But the grassroots sport became increasingly associated with gang fights and gambling, fueled in part by Hong Kong gangster films that romanticized pool halls as hubs of underground deals and street brawls. By the 1990s, authorities listed billiard rooms alongside gaming arcades, video screening rooms, and dance halls as places unfit for minors.

Then, in the early 2000s, a new generation of young professionals, including snooker champion Ding Junhui and nine-ball star Pan Xiaoting, found global success and brought the sport back into the spotlight. More recently, 28-year-old Zhao Xintong’s win at the World Snooker Championship in May once again reinvigorated people’s interest in pool, inspiring supporters back home to give it a go and challenging lingering stereotypes about the sport.

“Back when I was a kid, if you told someone you played pool, they would assume you were not a good person,” says Liu Hongda, a former snooker professional from Guangdong province. Liu began playing in 2003 at age 8. He says he faced constant disapproval from relatives and neighbors. “Some would ask why a little boy was playing pool instead of going to school,” he tells TWOC.

For those determined to go pro, the path was often physically and fiscally brutal. After a decade of chasing tournaments, Liu quit in 2013, defeated by the high costs. “It would cost about 300,000 yuan a year just to train and compete abroad,” Liu laments. When a friend brought him back to the sport in 2023, Liu was surprised at how much the scene had changed—from upgraded equipment to a new culture of discipline and professionalism. “The old image was gone.”

“It’s not like before,” echoes veteran coach Li Guohao. The 62-year-old moved his pool business from Hong Kong to neighboring Guangdong in the early 1990s as rising rents priced out many operators. According to Li, pool halls back then were especially messy. “Players were topless, smoking, and they would throw rubbish wherever they wanted,” recalls Li. Determined to change its unsavory image, he began to enforce house rules for his customers and trainees: no noise, no smoking, and a focus on discipline. Today, Li’s trainees are of all ages and include students, retirees, and white-collar workers. “The atmosphere has become much healthier, unlike the chaotic scene it used to be.”

Chinese pool, or eight-ball, has dominated amateur clubs since the early 2000s, thanks to its simpler, more flexible rules and easier gameplay on smaller tables and with larger balls than those used in standard snooker. By contrast, snooker’s steeper learning curve and pricier equipment make it the elite choice for serious competitors and less accessible for newcomers and venue operators. In Li’s hall, customers mostly play the domestic variant. “It’s easier for beginners to pick up, so more people are willing to try,” says Li.

For professional player Huang Qingning, the rise of Chinese pool was a lifeline. Having trained in American pool as a teenager, she switched over when Chinese pool tournaments began offering million-yuan prize money and drawing bigger fan bases across the world. “From stroke technique to overall strategy, everything was different. It felt like starting over,” says the 24-year-old from the southern Guangxi region.

Like Liu, the road for Huang wasn’t without hardship. At 15, long training hours caused her a serious shoulder injury. “My body hadn’t fully developed, but I needed to practice eight hours a day,” she recalls. She ended up switching hands and had to learn to play right-handed from scratch.

And while pool’s reputation has improved, traces of past prejudice remain. “Some parents still think pool halls are dirty places,” says Li. To counter this perception, professionals like Huang, Liu, and Li have all taken to social media platforms such as Douyin (China’s version of TikTok), sharing tutorials and pool basics with their tens of thousands of followers.

Social media has indeed become a game changer. On Douyin alone, the hashtag “pool competition” has racked up over 3 billion views with viral clips of quirky trick shots, teenage prodigies, and dramatic comebacks. In March, teenage player Zihan went viral after an unexpected trick shot at an unofficial Chinese pool tournament livestreamed on Douyin—some of her videos have garnered millions of views.

Official recognition of the sport has also gathered pace. Since 2014, the Chinese Billiard Sports Association has promoted snooker and Chinese pool in schools and universities in major cities, with some in Beijing and Chengdu making it part of their physical education programs. In 2023, the General Administration of Sport included pool in its national fitness campaigns, encouraging communities to install tables and organize amateur leagues.

The shift in perception isn’t limited to policy, but public attitude too. A survey by iiMedia this January showed that over 90 percent of the 1,558 pool consumers it surveyed said they would encourage their children to learn the sport, while over 64 percent would support their kids’ decision to train professionally.

Since last summer, Li has also led initiatives to introduce pool to students in Guangdong, offering classes in secondary schools and colleges to show them that pool is a discipline, not a vice. “It’s also a way to train your mind and personality,” he says. In April, Li even worked on a hit micro-drama, Master Arrives, about a food delivery driver who toils to become a snooker champion. The show garnered over 100 million views in just three days after its release. “We want people to see pool differently—not as shady entertainment, but as a skill, a discipline,” Li tells TWOC.

The cultural shift is visible in Li’s summer classes, where dozens of teenagers have now signed up to learn pool over their vacation. “Because many children don’t initially know much about pool—and some of them might actually be very gifted—they miss out on the opportunity to play because some parents still hold relatively conservative views,” Li tells TWOC. “But now that the general environment has grown healthier, parents can see a real career path for their children in the future.”

Li’s team also plans to organize amateur competitions in the future with financial support from major companies, which he hopes will attract more players. “Just like football and basketball,” says Li, “We can have different divisions, allowing people at the bottom to train and hone their skills and work their way up through these competitions.”

Liu also believes that kids don’t necessarily have to wait until after college to find a career path. “Is it possible to start developing a career in a non-traditional field from a young age instead?” he adds. Inspired by recent changes in the industry, Liu, turning 30 this year, plans to train in the UK and secure a spot in the elite 128-player World Snooker Tour before he turns 35. “That’s my ultimate goal.”

But for casual players like Yan, the appeal remains simple. She plays in her free time and tries to apply the skills she learns from online tutorials. Last month, she even took her mother to a pool hall for the first time. “Once you get the hang of it,” she laughs, “you never want to stop.”

Pool’s Big Break Among China’s Youth is a story from our issue, “Urban Renewal.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.