How performance artist Li Liao, famous for his 45-day stint on Foxconn’s assembly lines in 2012, became a delivery driver to pay the bills

On a Sunday morning at Shenzhen’s Pingshan Art Museum, one unimpressed visitor in shiny leather shoes drags away her young child as the boy waves at a selfie video of performance artist Li Liao, dressed in the yellow uniform of a food delivery driver. “What on earth are we looking at here? It’s not even high-end,” the mother complains.

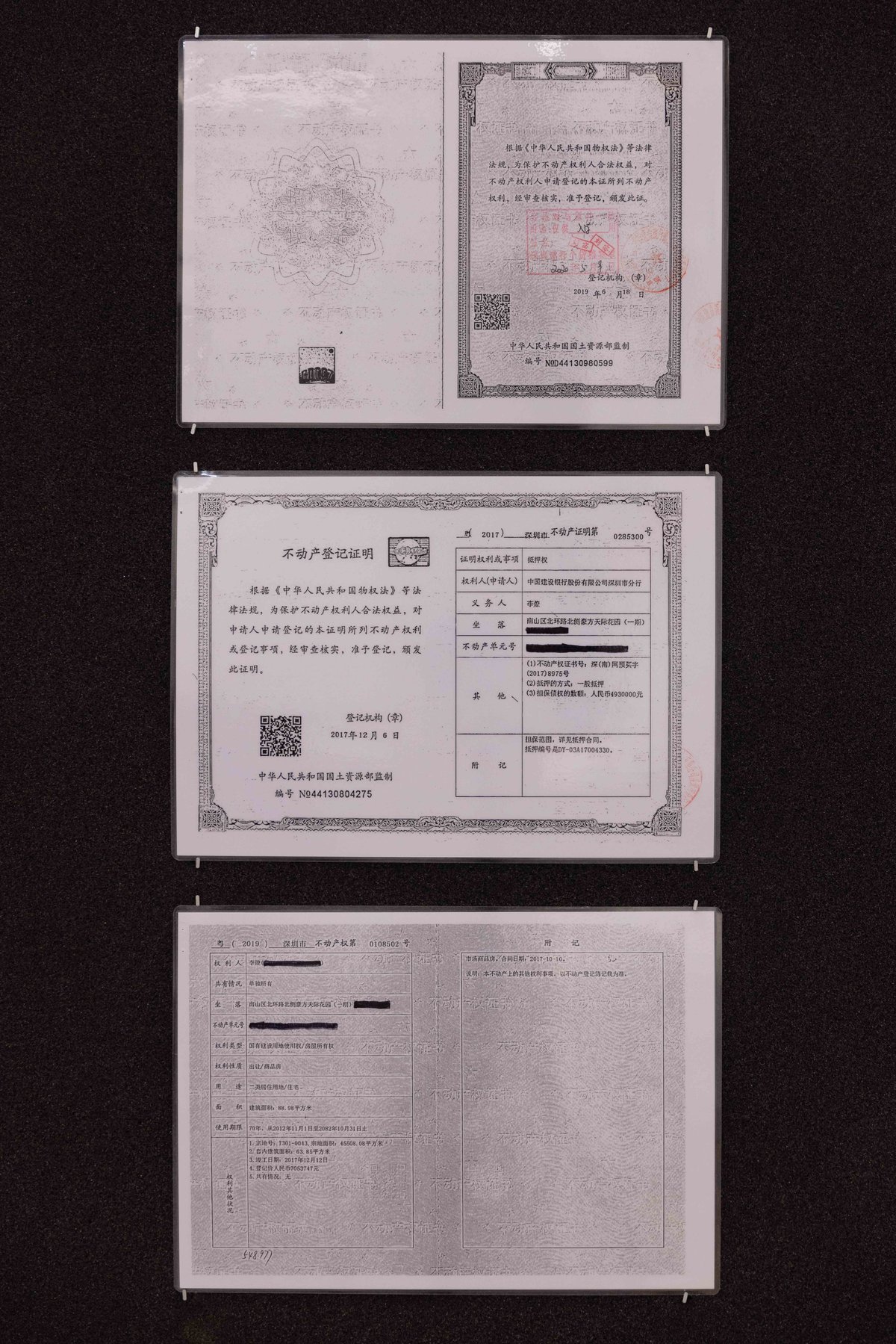

The next day, Li throws his head back and laughs into the lofty ceiling of the coffee shop where TWOC relates this scene to him. “Very good. I’m afraid of becoming a high-end artist,” he says. In 2022, when his wife Yang Jun, the family’s breadwinner, quit her job to start a fashion business, 40-year-old Li looked at the two or three decades of mortgage payments remaining on their new apartment in Shenzhen’s Nanshan district, and signed up to be a driver with Meituan, the largest food delivery platform in China.

After six months of struggling in his new job, Li drove his delivery scooter into the museum this March and parked it there in the middle of his new solo exhibition, “The Wife Went to Start a Business.” Dizzying screenshots of payments and rankings Li received from the Meituan app are pinned on the gallery walls. Elsewhere the exhibition consists of photos, videos, and installations highlighting the distress and triviality that emerged through this experience: a photograph of an arm with a stark tan line stretching across Shenzhen’s skyline; a visceral sculpture of a leg suspended in air with its knee hitting a road block, commemorating an accident Yang suffered on the back of Li’s scooter; the sound of Li humming a breezy song to various views of the road, mixing with the repeated “excuse me” he utters on the crowded sidewalks in another video to the right.

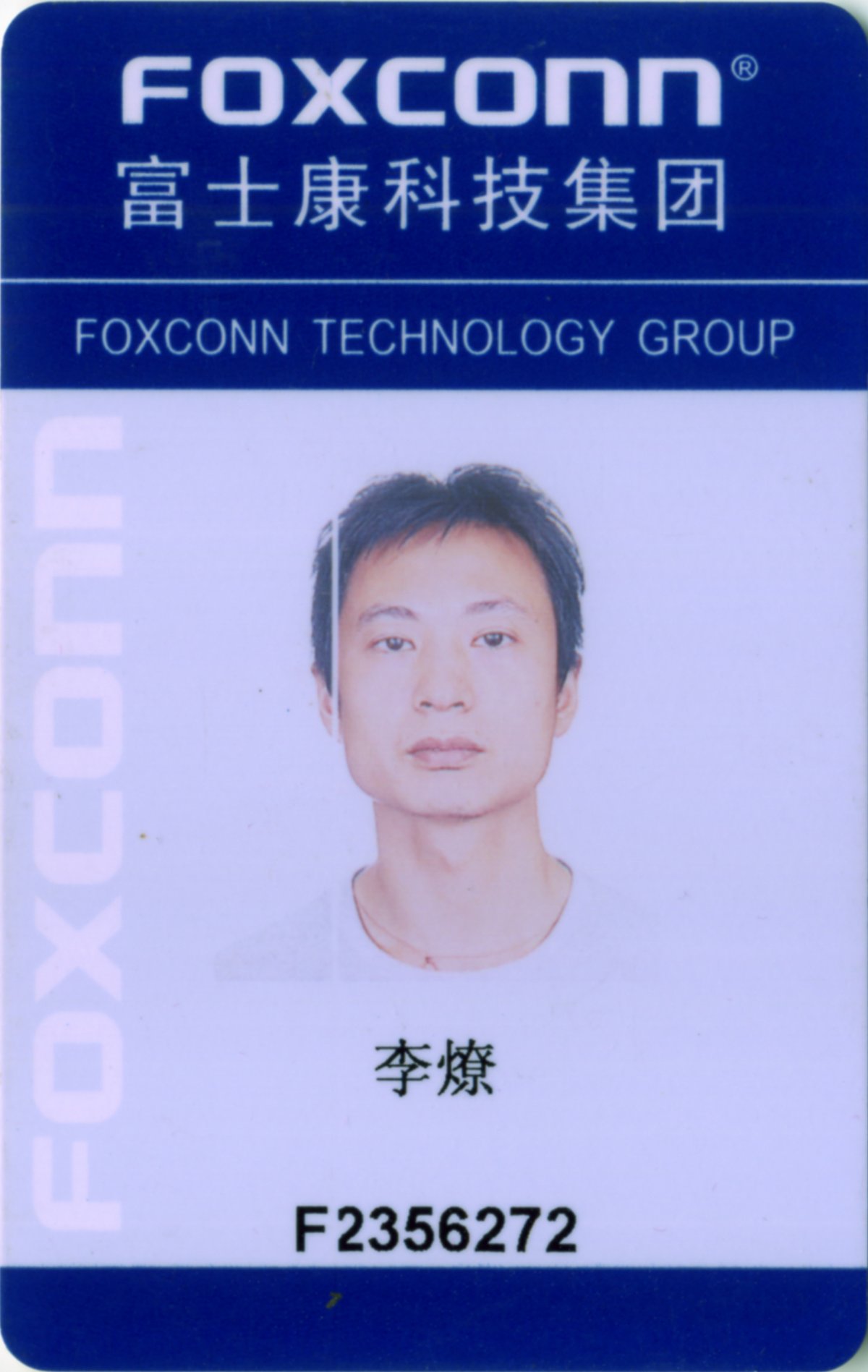

The project resonated with recent headlines exposing the precarious labor conditions of food delivery drivers, trapped inside big data algorithms which assign routes in order to maximize delivery volume and fines drivers for various small offenses like spilled food or tardiness. But this was not the first time that Li put himself through bitter labor for art. On November 23, 2012, Li emerged from 45 days on the assembly lines in Foxconn, a company then under fire for a spate of worker suicides, with a new iPad mini purchased with his paycheck and made in the factory. This he put on a pedestal in an art piece consisting of a lab coat and labor contract on the wall, and it brought Li international recognition for the disconnect he highlighted between consumption and labor in the current economy.

In his works, Li often turns himself into a processing machine: the reality of life feeds into one end, and gets transformed into feelings, observations, and absurd juxtapositions. “I did not create the artworks. I only discovered them,” Li tells TWOC, in between the apologetic laughter that is his trademark.

TWOC: How would you compare your recent project to your Foxconn project years ago?

Li Liao: In 2012, Apple products were still a luxury at least for small-time white-collar workers, while I didn’t even have a job. But when I saw them while shopping with my then-girlfriend, now wife, I really wanted them.

I thought about how my wife worked an office job, enduring oppression from the boss for a salary, then losing half a month’s pay on a luxury purchase like this. And then she’s back to laboring for her next paycheck. I might as well work for the manufacturer, so it would feel like directly buying what I made, cutting through the whole chain.

Both take labor as means, but I named the first project “Consumption,” because it started from such a desire. The current project is the opposite. Here, I use hard labor not to achieve consumption, but to push back against something that simply cannot be countered by hard labor—a feeling of lifting a heavy load with a short lever. For many among the middle class, that load is the mortgage, which for [Yang and I] might take another 30 years to pay off. When I turn [this phenomenon] into artwork, the absurdity is enlarged.

As artists, we feel for a lot of things and raise our voice, but we can’t provide real solutions.

What else did you want to raise a voice for through this project?

I really got a taste of how hard this job is. Also, the world seems to have become what we didn’t want it to be. When I was little, we were taught that labor was honorable, all professions were equal…but this isn’t the case in reality.

When you put on your delivery uniform, you can no longer enter some places. One time near a luxury mall, I really needed to take a dump, but they wouldn’t let me in. I challenged them, “Which of your rules says I cannot enter? Who gave you the rights?” The guard budged, but only if I took off my uniform jacket. Then he followed me and warned me repeatedly, “Don’t put it back on inside, or I’m done for!”

During heavy rains we got more orders because no one wanted to go outside. Heaven was rewarding us with money to earn, but there were also more hardships—more accidents, it was harder to be on time...You’d pray for the rain to stop, but you’d also want to make the money.

One night when the rain was especially heavy, I tried to enter a compound with two bags of goods, but the security guard wouldn’t let me in. “Go. Leave.” He waved me off. I got angry, “Can’t you talk decently?” He slapped the table and stood up, “Go! Leave!”

It was humiliating, really. I don’t understand this hostility between security guards and delivery drivers. [Perhaps] one is required to guard the property owners’ territory, the other is required to enter, so both are held in an impasse. One thinks they’re better than the other, but we’re all the same.

Often the middle class is like this too. They think they’ve learned certain ways the upper class carry themselves, believing it would make them upper class too. But it’s all a bait...an illusion.

You didn’t expect these things before you started the project?

No. I expected it to be physically demanding, but it sounded like a lot of freedom too: riding the little scooter around town, meeting people…I had these romantic notions.

But in reality, there’s so much pressure from the system. You live inside it—whether you get to rest, the speed at which you can afford to go, and the money you make, it’s all at the mercy of the algorithm.

My numbers were lousy. As much as I was breaking my back, I only made 7,000 yuan a month at most. There’s no way I could tough it out as much as [the real delivery drivers]. If I started at 7:20 a.m., the top-ranked drivers would already be out at 6. I usually packed up around 9 or 10 p.m., when my eyesight was already too blurry to see the roads well, but they would go on until midnight. This means they achieved better data, higher levels, so they could receive six orders during peak hours while I’d only have three.

There’s really no shortcut in this game. Only the grind.

What were your relationships like with your workmates?

I imagined some friendships and conversations with them: if they asked about my life, I would have confessed I’m an artist. But in the end, there weren’t many chances for interaction. Occasionally, I’d help someone do a delivery they didn’t want, and they’d buy me a bottle of water as a thank-you.

I am really not as resilient as many of them. I admired them, but sometimes I couldn’t look them in the eyes. This legendary driver once eagerly shared with me tips for different kinds of orders, but his eyes were emptily staring into the distance as he talked, not really looking anywhere. It was as if he could no longer think of anything else, like fun.

Sometimes he joined the dirty jokes in the group chat. But if you ran into him, he was always hustling. I once invited him for a beer, but he said, “You go ahead, I don’t drink.”

Many of your projects involved a shift in your identity, or even camouflage and deception. So how do you understand the “realness” in your work?

What I mean by “real” is not about truth or falseness, but authenticity in feelings.

In projects like this recent one, I needed to be fully there. I don’t like to watch people from the side and imagine what it would be like to be them, and then turn it into artworks. That’s not real. How do you create something without putting yourself in it? I want to be in real situations, and to feel the real pressure.

Even a mortgage could be part of the creative process. Most freelance artists are unwilling to fall into the mortgage trap. But, if you don’t carry these shackles, how would you know what the real world feels like? How would you know what it’s like to wake up in the middle of the night, feeling tragically desperate about the many years of payment ahead?

Someone wanted to film me during the project, proposing to sit behind me on the scooter to “feel” what it’s like to deliver goods. I thought, you won’t feel anything. Sure, maybe you would find some fun and intrigue, but you won’t know how it feels when an imperfect delivery costs you money, when customers cuss you out, or the pressure that comes from the system. You would only be sitting there watching someone’s performance in front of you.

Has the core of what you want to express changed over the years?

At its deepest, no. On one hand it’s an output from the heart, on the other it’s about externalizing a small-town young man’s sense of inferiority.

I often tell people that when you try to hide the sense of inferiority, you would appear even less confident. But when I wear my insecurity on the sleeve and base my art on it—if you find me less “high-end,” I’ll flaunt that—it becomes a form of confidence.

Images courtesy of Li Liao and Shenzhen Pingshan Art Museum

When Art Meets the Authenticity of Labor is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.