Explore the multifaceted life of Song Emperor Zhao Kuangyin and the idioms it inspired

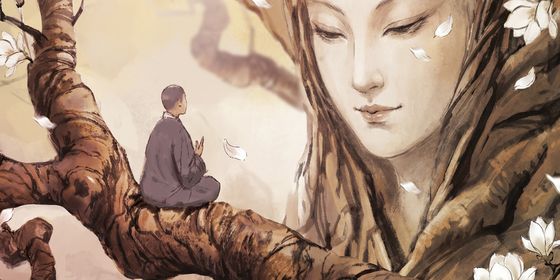

Following the global success of Black Myth: Wukong in 2024, China’s video game industry is increasingly focused on reinterpretating China’s own historical and cultural heritage. One of this year’s most popular releases was NetEase’s Where Winds Meet, a wuxia role-playing game set in the turbulent era spanning the late Five Dynasties (907 – 960) and early Northern Song (960 – 1127) period.

Amidst the swordplay, the journey leads to a pivotal encounter with a crucial guide: a character of formidable martial skill known as Zhao Dage, or “Big Brother Zhao.” Astute players quickly realize this is no ordinary NPC. In fact, his historical prototype is Zhao Kuangyin (赵匡胤), the founding emperor of the Song dynasty (960 – 1279).

In the game, Zhao Dage moves the story along and offers guidance and help with tasks. But the real Zhao Kuangyin was no mere sidekick advising the protagonist. He was an emperor thrust onto the throne by circumstance, a statesman whose shrewd political maneuvers laid the foundation for three centuries of civil governance, yet one who died without ever reclaiming the “sixteen prefectures of Yan and Yun (燕云十六州),” an area from present-day Beijing to Datong in northern Shanxi. These lost territories are directly referenced in the game’s Chinese title, which literally translates as “Sixteen Sounds of Yan and Yun (燕云十六声).”

It’s time to put down the controller and meet the real Big Brother Zhao.

Draped in yellow

Zhao Kuangyin, born in Luoyang in 927, was a ruler who grew up in chaos. Twenty years earlier, the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) had collapsed, and China entered the period known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907 – 979). Over 53 years, five short-lived dynasties rose and fell in central China, with 14 emperors ascending the throne—most through military coups. Warlords carved up the land, fighting against each other, and social order disintegrated.

The son of an imperial guard commander, Zhao followed in his father’s footsteps and joined the military at a young age. Soon, he distinguished himself in the court of the Later Zhou dynasty (951 – 960), rising swiftly to become a senior commander of the elite imperial guards.

Read more about ancient Chinese emperors:

- Five Chinese Emperors Who Rose from Humble Beginnings

- Elixirs of Power: Chinese Emperors’ Quest for Immortality

- Why Netizens Can’t Stop Arguing About Qing Court Gossip

In 959, Emperor Shizong of the Later Zhou launched a northern expedition against the powerful Liao state. The campaign started well, but the emperor fell gravely ill on the march and died soon after at just 39, leaving the throne to his seven-year-old son. With a young ruler and a suspicious court, the Later Zhou was suddenly thrust into a precarious existence.

The following year, urgent reports reached the court, claiming a joint invasion by the Northern Han and Liao. The court then ordered Zhao to lead the main imperial army north to defend the border. However, after leaving the capital Kaifeng, the army did not rush to the frontier. Instead, it halted at Chenqiao Post Station, about 20 kilometers northeast of Kaifeng. One February dawn, mutiny broke out in the camp. Senior officers draped a pre-prepared yellow robe—the imperial outfit—over Zhao and proclaimed him the new emperor.

According to the History of Song (《宋史》), the official record of the dynasty compiled in the 14th century, Zhao was drunk that night and had no involvement in the revolt. To stabilize the army’s morale, he was forced to accept the yellow robe and proclaim himself the new emperor. He secured a pledge from his men: to do no harm to the Later Zhou dowager and child emperor, and to refrain from looting the capital or harassing its officials and citizens. The army immediately turned back toward Kaifeng. With many allies among the capital officialdom and the core imperial forces under his command, the city offered no resistance. The child emperor was forced to abdicate, and Zhao ascended the throne, founding the Song dynasty with its capital in Kaifeng.

This transfer of power, which coined the chengyu “draped in the yellow robe (黄袍加身 huángpáo jiāshēn),” is celebrated for its peaceful nature, avoiding the mass slaughter of the deposed that was typical of the era. Yet today, many scholars argue that the details, including the suspicious invasion alarm, the army’s unusual stop at Chenqiao, and the ready-made yellow robe, all point to a highly organized operation. Consequently, while official histories stress Zhao’s passivity and reluctance, many believe it was a meticulously planned military coup directed by Zhao and his inner circle.

Relinquishing power over wine

Having been “draped in the yellow robe” by his own troops, Zhao, now the emperor, understood better than anyone else the threat military power posed to the throne. According to historical works from the Song dynasty, such as Records of Conversations by Dingwei (《丁晋公谈录》) and Private Notes of Scholar Wang Wenzheng (《王文正公笔录》), Zhao held a palace banquet in 961, barely a year and a half into his reign, inviting several senior imperial guard commanders to drink together. At the banquet, Zhao dismissed the servants and confessed his anxiety, saying he couldn’t sleep peacefully through a single night. When the alarmed generals asked why, he went straight to the point: “What if your own subordinates, craving wealth and honor, were to drape the yellow robe on you one day? Even if you wished to refuse, could you?”

This rhetorical question struck the generals as prescient. The next day, they all pleaded illness and resigned, voluntarily surrendering their direct command of the imperial guards. In return, Zhao bestowed upon them prestigious but largely ceremonial military governorships, vast wealth, and marital alliances with the imperial family.

Although modern scholars note that the story has likely been embellished, this narrative, summarized in the idiom “using a cup of wine to remove military power (杯酒释兵权),” has long been held up as a model of resolving latent crises through frankness and wisdom between ruler and ministers.

Accordingly, in the dynasty’s early years, Zhao curtailed the administrative and financial powers of military governors and dispatched centrally-appointed civilian officials to govern prefectures, ending the old era of politics by force and laying a stable foundation for the Song’s civilian-oriented rule.

A realm shared with scholar-officials

With military authority secured, Zhao turned his attention to a more fundamental task: rebuilding a society torn apart by fragmentation and warfare. Regarding the economy, he abolished the practice of military governors withholding local tax revenues and centralized financial authority. To prevent officials from imposing unreasonable levies, he issued China’s first commercial tax law and posted the tax rates for major commodities outside each tax office. These policies gradually dismantled local economic barriers, laying the groundwork for a prosperous national market during the Song rule.

Culturally, Zhao dramatically expanded the quota for candidates selected through the imperial examinations, opening the path to officialdom to more scholars. A pivotal moment came in 973, when Zhao personally presided over a re-examination after questioning the initial results. This act reinstated the “Palace Examination” system, meaning the emperor personally conducted the final test. As a result, all successful candidates became “students of the emperor” rather than the examiners’ proteges, dismantling private patronage networks. In turn, a large scholar-official class, whose status was directly tied to the emperor, quickly emerged.

This principle provided the scholar-official class with unprecedented personal security and space for political discourse, forming the cornerstone of the Song’s distinctive political ecology of “joint governance by the ruler and his ministers.” Legends even hold that Zhao left a secret covenant in the Imperial Ancestral Temple, stating: “Do not kill scholars or those who present remonstrances.” While not recorded in the official dynastic histories, this pledge is widely cited in Song-era private notes and memoirs, and its spirit undoubtedly permeated the entire Song period.

The untaken frontier

As the dynasty’s founder, Zhao’s greatest regret was his lifelong failure to reclaim the “Sixteen Prefectures of Yan and Yun.” Ceded to the Liao state around 938, this strategic territory served as a natural defensive barrier south of the Great Wall against northern cavalry. Its loss left the Central Plains exposed, which was a constant threat hanging over the dynasty.

According to Fleeting Gossip by the River Sheng (《渑水燕谈录》), a collection of notes by the Northern Song official Wang Bizhi (王辟之), Zhao established a special treasury within the palace to accumulate wealth. He reportedly confided his long-term plan to close aides: “When the savings reach five million strings of coins, we will send an envoy to the northern foe to ransom the prefectures beyond the mountains; If they do not comply with us, we will then use the treasury’s wealth to recruit warriors and plan an attack to seize them.” But the plan broke when Zhao mysteriously died in 976.

His successor and younger brother, Emperor Taizong, abandoned the plan to buy back the lands. He launched two massive northern expeditions in 979 and 986, both ending in disastrous defeats. Thereafter, Song’s strategy turned inward and defensive. During the reign of the Song’s third ruler, Emperor Zhenzong, after 25 years of constant conflict and Liao’s growing aggression, the dynasty signed the Chanyuan Treaty in 1005, agreeing to annual tribute payments in exchange for long-term peace. “Reclaim the Yan and Yun” gradually transformed from a practical goal into a deep-seated collective aspiration.

The lands remained beyond the effective control of Han-ruled dynasties for over four centuries, until they were finally recovered in 1368 under the order of Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), who, like Zhao Kuangyin, rose through military distinction.

Thus, when we roam the virtual world of Where Winds Meet today, what we encounter is more than the elegance and prosperity of the Song. The game’s name itself also carries the weight of an unfilled, enduring aspiration that spanned the entire dynasty’s existence.