A melodious dialect from the city of heroes and food

For over a decade, The World of Chinese has been offering modern Chinese-language instruction from street talk to social phenomena to character tales. With 129 officially recognized dialects (方言), though, we have barely scratched the surface of everything there is to learn.

On select Fridays, TWOC will be presenting a basic lesson on speaking like a native of a certain region of China.

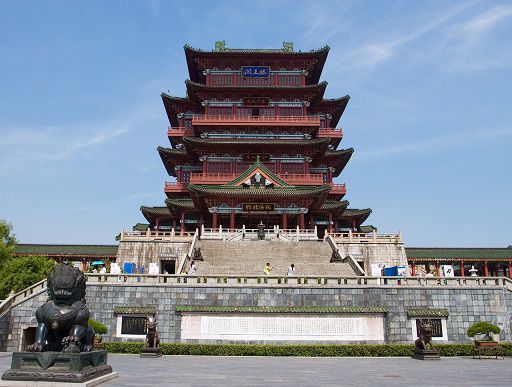

“At the Pavilion of Prince Teng in Yuzhang/ There are no sounds of princes’ carriages / Only a moon outside the window/ Lighting up the river-town deep into the night,” the 13th century poet Yu Ji (虞集) writes in “On Prince Teng’s Pavilion,” describing the most famous landmark of Nanchang (南昌).

Historically known as Yuzhang (豫章) or Hongdu (洪都), the capital of Jiangxi province is a laid-back city located on the banks of the Gan River. Besides the pavilion, it’s best known for the Nanchang Uprising of August 1, 1927, the first major military conflict between the Nationalist Party and Communist Party of China. This date is now regarded as the founding of the People’s Liberation Army, and many place names and historical sites in Nanchang, the “City of Heroes,” reflect its military heritage.

The riverside Pavilion of Prince Teng is one of the “Ten Great Sceneries of the Jiangnan Region” and “Four Great Towers of China” (Pixabay)

Nanchang’s fangyan seems to embody this curious mix of Jiangnan elegance with hot-blooded military fervor (and peppery local cuisine). It’s more accurately known as the Changdu branch of the Gan dialect (赣语), one of the eight Chinese dialect groups, and spoken across north-central Jiangxi and the southernmost part of Hunan. Nanchangese is a melodious dialect that frequently uses the high-level (first) tone and many x, q, and s sounds, giving it a sibilant and excited air.

Here are a few basic features of the dialect (tone marks for Nanchangese are approximate, due to the difficulty representing the dialect’s seven tones using the four standard diacritics):

- Similar to many Jiangnan dialects, the sh, zh, and ch sounds become s, z, and c, respectively

- The h sound becomes an f sound, the opposite of some Fujian dialects: 花 (flower), huā in Mandarin, is pronounced fā

- The pronouns wǒ (我, I), nǐ (你, you), and tā (他/她, him/her) become, respectively, ǒu (偶), nǎi (倷), and qú (佢)

- The word xīlī (稀哩) replaces shénme (什么, what); 呷稀哩哟 (gā xīlī yo, what is this?) is considered the quintessential Nanchangese phrase

- The particle xī (系) is used for emphasis at the end of questions, such as 倷伓恰嘞系? (nǎi pī qiā le xì, Why have you stopped eating?)

- Adverbs often go after the verb, not before: For example, one says 多穿一点 (duō chuān yidiǎn) in Mandarin to tell someone to put on more clothes, and 穿多滴(cuān duō dī) in Nanchangese

- Verbs also go after the object. 你吃饭了没? (nǐ chīfàn le méi) in Mandarin becomes 倷饭恰了啵? (nǎi fān qiā le bo), for “have you eaten yet?”

- Nanchangese is famous for vivid words of colors, such as 雪白 (xuē ba, snowy white) for white, 灭黑 (miè he, pitch black) for black, and 宣红 (xuān fōng, a type of red glaze on ancient pottery) for red

Since the 1980s, Gan has become heavily influenced by Mandarin, and is losing its speakers and even some of its features. In 2013, public opinion was polarized by the inclusion of “Cured Bacon Stir-fried with Sage,” a classic Nanchangese folk song (and dish), in a primary-school music textbook, with some Nanchang natives feeling ashamed of their dialect, while others defended their heritage. In 2017, a Nanchang Evening News poll found that 70 percent of parents did not speak Nanchangese to their children due to fears it will interfere with learning Mandarin. Today’s speaker, who is in her early 40s, still uses Nanchangese in daily life, but her 12-year-old son can only understand Nanchangese, and cannot speak it.

Rice noodles are another Nanchang delicacy, served either stir-fried or, as here, boiled and tossed with chopped chilis (photo by Hatty Liu)

Local preservation efforts include Nanchangese speech competitions and performances of crosstalk in dialect. Here are some classic New Year greetings to practice in Nanchangese:

1.

Guōniān le, zūdǎigà xīnniān kuǎile, wànsī rūyì

过年了,祝大噶新年快乐,万事如意!

It’s the New Year! Wish everyone a happy new year, may all your dreams come true

2.

Lǎoninga cángmiàng beisuī, xīyāzī mángzuāng mángdài

老您噶长命百岁,细伢子莽壮莽大

A long life to the elderly, and good health for the children

伢 (ya) is the word for “child” in many southern dialects, and 细伢子means “little child,” though 细 (literally, “thin”) is probably just phonetic and not meant to be taken literally. 莽 means “thick” or “rough,” and 莽壮莽大 is a wish for children to grow big and sturdy

3.

Sǎngbàn ga gōngzuō shǔnlǐ, dǔ sù ga hǎosàngzi hēxǐ

上班噶工作顺利, 读书噶好桑子和习

[Hope that] work goes well for those who work, and those in school will study hard’

好桑子 is an adverb meaning “to do [something] well,” like 好好 (hao hao) in Mandarin. 和习 is an old word meaning “to learn to sing a song,” but here in sing-songy Nanchangese, it refers to academic study.

4.

Zǎilīzī yuē zǎng yuē shuāi, nǚzāizī yuē zǎng yuē kēiqi

崽里子越长越帅,女崽子越长越尅气

[Wish that] boys will grow more handsome, girls will grow prettier

崽 refers to one’s own child, or son, in many dialects. In Nanchangese, boys are 崽里子 while girls are 女崽子. The word 尅气 means “pretty,” though some say the first character is not pronounced kēi but kiē, which is inexistent in Mandarin.

5.

Finally, as one might guess from this lesson, the Nanchangese love to talk about food. Here is a video in the dialect discussing locals’ favorite topic: