What if the renowned 20th-century writer was alive to splurge on Singles’ Day?

During this year’s Singles’ Day shopping festival, netizens fell back on one of the country’s favorite writers to describe their online splurges. “When Lu Xun paid his balance (当鲁迅付完尾款 Dāng Lǔ Xùn fùwán wěikuǎn)” became a trending topic on Weibo, with users wondering what the 20th century literary master would say if he had splurged during the shopping extravaganza just as today’s online spenders do.

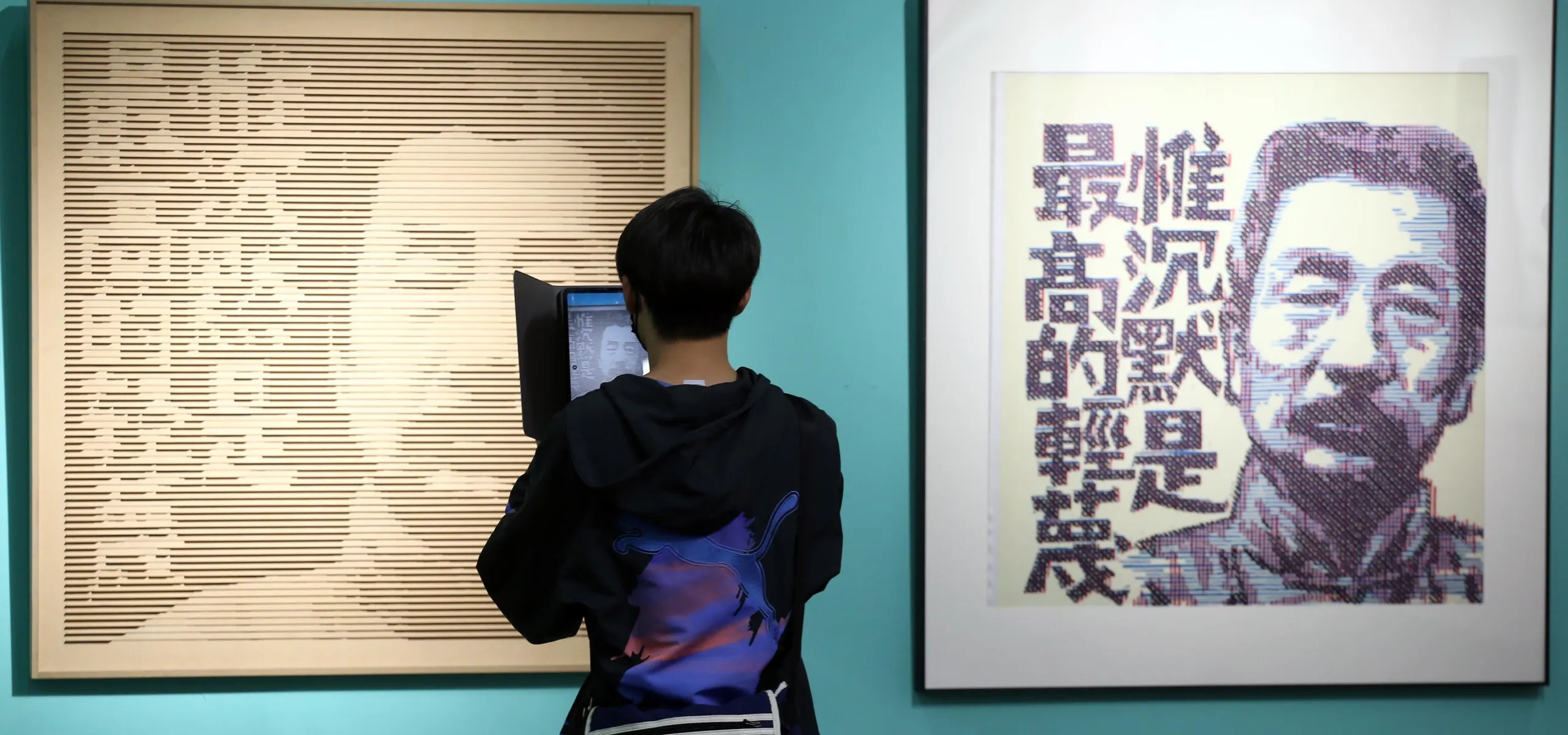

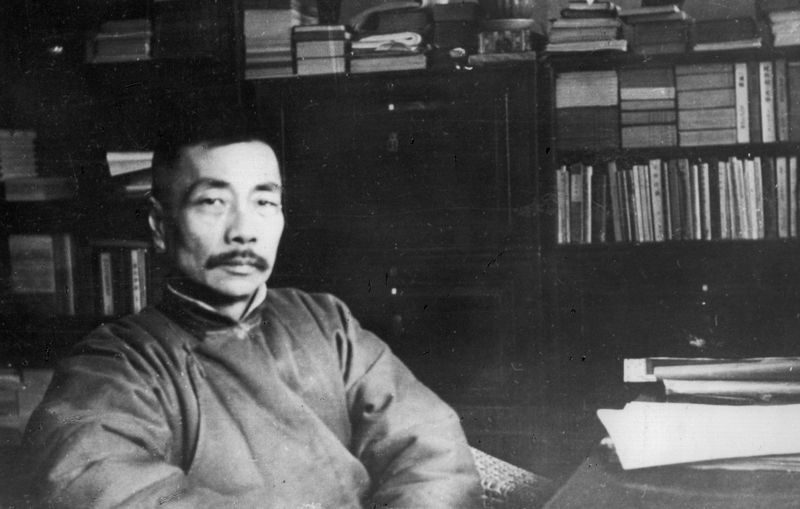

Lu Xun, whose real name was Zhou Shuren (周树人), was perhaps China’s foremost writer of the 20th century, and is now compulsory reading for Chinese schoolchildren. His penetrating words still resonate with millions, and now netizens too have latched onto his biting prose, dripping with satire and irony, to describe their anxieties.

This so-called “Lu Xun Style (鲁迅体 Lǔ Xùn tǐ)” adapts the master’s words to modern situations. For example, under the hashtag “When Lu Xun paid his balance,” netizens played on a Lu Xun passage to reference their own poverty after Singles’ Day: “I am always ready to think the worst of my poverty, but I could neither conceive nor believe that I could stoop to such extreme destitution (我向来不惮以最极端的恶意来揣测我的贫穷,然后我却不料,也不信,竟会穷到这地步 Wǒ xiànglái búdàn yǐ zuì jíduān de èyì lái chuǎicè wǒ de pínqióng, ránhòu wǒ què búliào, yě bú xìn, jìng huì qióngdào zhè dìbù).”

The original version of this dramatic quote comes from Lu’s short story “In Memory of Miss Liu Hezhen (《记念刘和珍君》)”: “I am always ready to think the worst of my fellow countrymen, but I could neither conceive nor believe that we could stoop to such despicable barbarism (我向来是不惮以最坏的恶意,来推测中国人的,然而我还不料,也不信竟会下劣凶残到这地步 Wǒ xiànglái shì búdàn yǐ zuì huài de èyì, lái tuīcè zhōngguórén de, rán’ér wǒ hái búliào, yě bú xìn jìng huì xiàliè xiōngcán dào zhè dìbù).”

Meanwhile, the short story “Diary of a Madman (《狂人日记》),” published in 1918, has been repurposed from its original form as a scathing critique of Chinese society in which a man gradually begins to realize he lives in a society of cannibals, into a self-deprecating lament at all the money spent on online shopping deals on November 11 and December 12. For example: “I tried to look at my history, but my history has no chronology, and scrawled over each page are the words: ‘Double 11’ and ‘Double 12.’ Since I could not sleep anyway, I read intently half the night, until I began to see words between the lines, the whole book being filled with the two words: ‘No Money’ (我翻开历史一查,这历史没有年代,歪歪斜斜的每页上都写着“双十一”“双十二”几个字。我横竖睡不着,仔细看了半夜,才从字缝里看出字来,满本都写着两个字“没钱” Wǒ fānkāi lìshǐ yì chá, zhè lìshǐ méiyǒu niándài, wāiwāixiéxié de měi yè shàng dōu xiězhe ‘Shuāng Shíyī’ ‘Shuāng Shí’èr’ jǐ gè zì. Wǒ héngshù shuìbuzháo, zǐxì kànle bànyè, cái cóng zìfèng li kànchū zì lái, mǎn běn dōu xiězhe liǎng gè zì ‘méi qián’).”

The original describes historical texts full of the words “virtue and morality (仁义道德 rényì dàodé),” but between the lines the whole book was filled with two words: “Eat people (吃人 chī rén).”

Lu’s frustration at conventional doctrine, Confucian tradition, and social apathy during early 20th century China has also been repurposed by modern netizens to voice their indignation about their money troubles, job pains, romantic failings, and the “involution (内卷 nèijuǎn)” of society. This pioneer of modern Chinese literature has been reborn as a champion of “emo” netizens.

Using Lu Xun style, netizens complain about being underpaid and flirt with quitting their jobs. “Unless we burst out and quit, we shall perish in this job (不在辞职中爆发,就在打工中灭亡 Bú zài cízhí zhōng bàofā, jiù zài dǎgōng zhōng mièwáng)!” they declare dramatically. Lu Xun’s version, a cry against passivity in society, read, “Silence, silence! Unless we burst out, we shall perish in this silence! (沉默啊!沉默!不在沉默中爆发,就在沉默中灭亡!Chénmò a! Chénmò! Bú zài chénmò zhōng bàofā, jiù zài chénmò zhōng mièwáng!)”

In “In Memory of Miss Liu Hezhen” Lu writes: “The true warriors dare to face up to the misery of life and confront dripping blood (真的猛士,敢于直面惨淡的人生,敢于正视淋漓的鲜血 Zhēn de měngshì gǎnyú zhímiàn cǎndàn de rénshēng, gǎnyú zhèngshì línlí de xiānxuè).” Netizens subsequently turned that into a phrase about romance: “The true ‘single dogs’ dare to face up to the pressure to marry from their relatives and confront the affection of their friends in love (真的单身狗,敢于直面亲戚的催婚,敢于正视朋友的狗粮 Zhēn de dānshēngǒu, gǎnyú zhímiàn qīnqī de cuīhūn, gǎnyú zhèngshì péngyǒu de gǒuliáng).”

With countless more imitations of Lu Xun flooding the internet, some even forgot the original quotes. As with Confucius, it’s vogue to attribute anything written in a wise or literary style to Lu’s influence. “If you are not sure who said a famous quote, just say it was Lu Xun (如果拿不准一句名言是谁说的,就说是鲁迅说的 Rúguǒ nábuzhǔn yí jù míngyán shì shéi shuō de, jiù shuō shì Lǔ Xùn shuō de),” one netizen quipped on Weibo.