Netflix remake of beloved teen drama slammed for slavish devotion to “socialist values”

Creatives will always find an excuse for terrible reviews. Director and screenwriter Bi Zhifei imputed the failure of his film, Pure Hearts: Into Chinese Showbiz, to negative comments on Douban. Director Feng Xiaogang argued his comedy Personal Tailor only flopped because critics “didn’t know anything about film.”

But recently, Fang Hui, writer of the 2018 remake of classic romance-drama Meteor Garden, found a new scapegoat—the (recently renamed) State Administration of Radio and Television.

Meteor Garden hits small screens worldwide this month —courtesy of a Netflix deal—but has already been slammed by Chinese audiences. At 3.1 out of 10, the show has become one of the lowest-rated items Douban, and some are already concluding that it’s “the worst adaption ever.”

To be fair, it’s always risky to remake a classic, especially a cultural phenomenon like Meteor Garden. Adapted from Japanese manga series Boys Over Flowers, the original Mandarin-language Meteor Garden, produced in Taiwan in 2001, was known as “the first idol drama” in the history of Chinese TV, launched the acting career of singer Barbie Hsu, who played protagonist Shancai, and gave rise to a short-lived boy band called F4, named after the aristocratic clique who form the central love triangle with Shancai.

Though the 90s posters look embarrassingly dated today, the DVD sold over 300,000 copies when it first aired, and the show remains a powerful cultural memory for the post-80s and post-90s generations. Aside from this Taiwanese drama, Boys Over Flowers was adapted as Japan’s Hana Yori Dango, the Korean Boys over Flowers, the Chinese mainland’s With the View of Meteor Shower, and even an American remake called Boys Before Friends (rated 3.2 out of 10 on IMDB).

The latest remake has attracted even more haters than usual, with the Global Times arguing that the backlash was due to the how the show “violated the socialist values,” with several storylines depicting domestic violence, money worship, misogyny, and school bullying. (The Taiwanese version, it must be noted, was banned on the mainland for the same reason 17 years ago)

Contrary to what the Global Times believes, though, the new show might be flopping because it features too many “socialist values.”

First of all, the four main boys don’t look so rich anymore. In the 2001 version, when filthy rich male lead Daoming Si tries to impress Shancai, he boasts that “If I wanted, I could buy you the Eiffel Tower.” In the 2018 version, this has become “If you play mobile games, I can give you as much virtual currency as possible…I can buy you snacks when you have class…We can travel once a year.”

Swoon.

The F4, moreover, are no longer “arrogant fuerdai (‘rich second-generation’),” but “handsome, tall, optimistic boys, all of whom show extraordinary talents in their studies.”

And when a fuerdai girl sends a gift to the female lead, she doesn’t choose luxury shoes, as the same character did in the 2001 version. Instead, she gets cheap knockoffs.

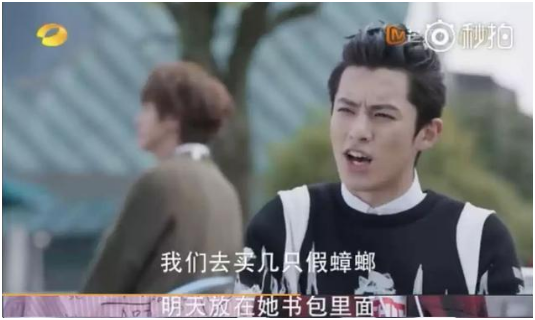

F4’s unpleasant tendency to bully is also tone down to playground pranking:

“Let’s go buy a few fake cockroaches, and put them in her backpack tomorrow”

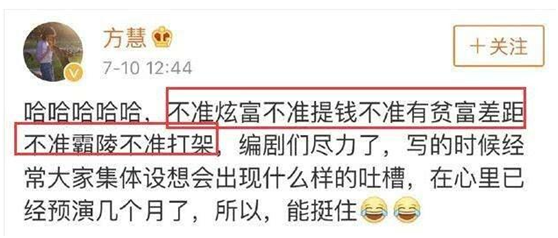

With netizens complaining that the show was watered down and inane, its screenwriter has jumped into the fray, claiming that all the changes were made to appease the censors:

Can’t show off wealth, can’t mention money, can’t show income gaps, can’t have bullying, can’t have fighting…The screenwriters have tried their best. When we were writing, we often imaging what kind of bullying would appear, and we have been rehearsing this in our mind for months (Weibo)

Not all viewers are buying the excuse, though:

Did they also say you couldn’t use your brain?