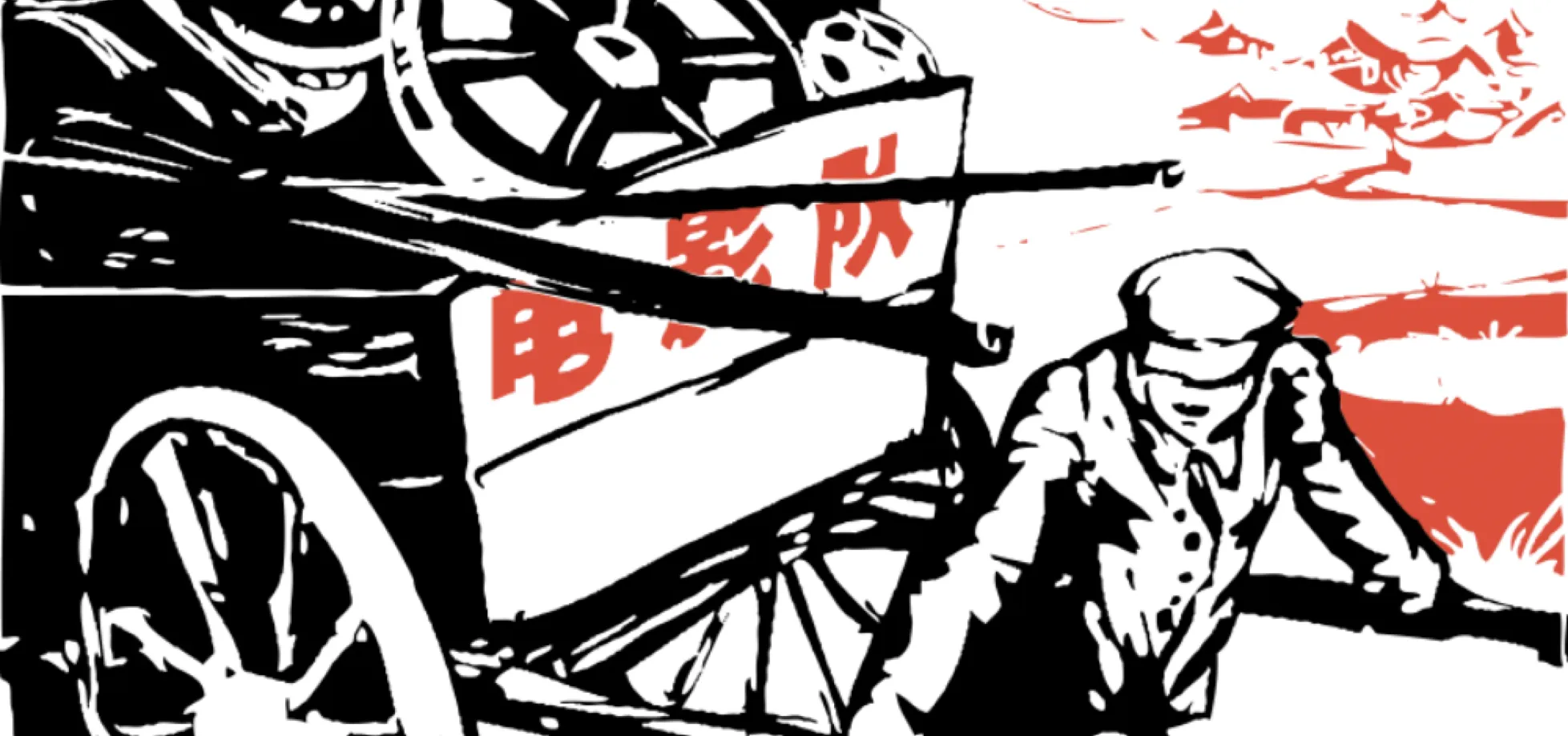

Zhao Jishan, “the movie man,” spent years dragging a mobile cinema through rural China to bring entertainment to the villages

Zhao Jishan was the movie man. It was a job he didn’t even want. In 1974, Zhao was a hard-working, well-spoken, well-read worker with a penchant for drawing. He worked at the Communications Office of the Transportation Bureau writing news about the progress of road works. He knew nothing about mobile cinemas, but that was what the Bureau asked him to work on.

It was a temporary job, not at all a step toward the promotion that he had been waiting for—a promotion to “permanent worker” status. But that year, the government had ordered films to be shown in all rural areas of China. Zhao was picked to lead a team that would travel to different villages playing movies for farmers on a mobile screen and projector.

He refused.

The next year, they approached him again to lead a mobile cinema unit. He resisted again, but he no longer really had a choice. He had the skills for the job, so, unwillingly, Zhao took command of the Pangjia Town Movie Unit.

For three years, he and two other men pulled a cart stacked high with reels, slides, a screen, a 30-kilogram projector, generator, record player, loudspeaker, microphone and poles. They brought news, entertainment, and patriotic values to 49 villages in the local township. Their biggest enemies were rain and equipment failure. A drizzle required pitching umbrellas over the projector; a downpour meant a delayed screening. If the projector broke, they would stay in a village for as long as it took to get the equipment running again.

Villages in the township were, at most, an hour apart by foot. In the morning, the unit pulled its gear across the fields. Arriving before noon, they stayed as guests in farmers’ homes and would sweep their hosts’ yards in good faith. In the late afternoon, with lunch digesting in their bellies, the movie men woke from their naps and began pulling the film reels out of their bags.

As team leader, Zhao earned 35 yuan a month, about the starting salary of a university graduate at the time. The salary was enough for Zhao, but he was also well-received by the villagers. For lunch, they had steamed buns made from the village’s best flour. As the movie men ate, children would gather to watch.

Once, Zhao stopped eating and extended a bun to the curious young faces.

“Eat up,” the oldest child said. “You’re the movie man!”

Zhao frowned. Over 100,000 mobile cinema units pulled heavy carts all over China. There were movie men like him everywhere.

But he accepted the hospitality. Magic shadows dancing on screen put smiles on farmers’ faces at the end of a laborious day. Movies were a way for people to connect to the whole country—thousands of other villages were watching the same reels.

During one showing, Zhao went into a field to relieve himself. As he approached a tree, he saw a young couple sitting holding hands.

“Hey, aren’t you from another village?” Zhao asked the young man.

“Yes, comrade. I came to watch the movie…You can see my pass. I have permission,” the young man stuttered.

“I see, I see…Well, you might want to go back and watch the movie,” Zhao said with a wink. The couple hurried off.

At 24 years old, Zhao was still single. He chuckled at the boys who came from other villages to chase their lovers on film nights. Working on the road and holding a temporary job, he had little room for romance. He entertained himself by getting drunk with village leaders.

One night, a chubby official challenged Zhao to a drinking contest. He boasted that he could drink Zhao under the table: “I’m gonna beat you like the PLA beat those imperialist thugs!”

As they walked to the official’s house, a gaggle of children trailed behind them. The little ones tried to sing the revolutionary song from the film they had just watched. At the house, a table was set with small cups of baijiu and a large plate of peanuts. Outside the house, the song subsided and eager faces peeked over the window sills.

Zhao and the official washed the peanuts down quickly. “Drink another,” the rotund instigator motioned. The movie man smiled, poured the harsh liquid down his throat and told a joke. “A man searching for his die [爹, a slang term meaning father] approached a film unit asking to use their loudspeaker. He began to call, ‘爹!’ Everyone in the village heard, ‘Father!’ But no one knew who he was looking for—it didn’t occur to him to use his father’s name!”

The official roared and imitated, “爹!” As he poured more baijiu into Zhao’s cup, he kept repeating the punch line. He would call out “father” at least a dozen more times before the end of the night.

The next morning, Zhao cursed his throbbing headache, pulled leather straps over his shoulders and began pulling the cart to the day’s destination. A few hundred meters out of the village, the cart sank into a crater of mud. The team, still half-drunk, pushed and pulled, but it wouldn’t budge.

“Hey, hey, movie man!” The scrawny kids from the night before came running over. There were at least ten of them. They gripped the wheels with little hands. The soles of their bare feet slipped in the gooey wet earth as they helped heave the cart out of the mud. Ten grubby faces cheered, and Zhao cheered as well. He turned back to wave at them as his mobile cinema unit went on its way.

It was a hot 1977 summer day in Shandong province when Zhao received news that he could move up to a permanent position in the county. A large crowd formed in the small clearing where he was preparing a screening. Farmers and village officials; the old and the young; lovers and friends; all waited with anticipation for Zhao and his crew to finish their preparations.

“Hurry up, uncle!” a young boy yelled from the back.

“All in good time,” Zhao made a funny face at the boy and finished putting up the 2.5-by-2-meter screen. Nearly 1,000 people had gathered, jostling for space. A group of agile men climbed onto a brick wall. Some families even took up position behind the screen. No one wanted to miss the movie.

The most junior member of Zhao’s team arranged the reels in playing order. Zhao checked the projector to make sure that it was properly focused. With the flick of a switch, the machine hummed to life. Nothing appeared on the screen.

“I thought I told you to get the slides!” Zhao said to the junior. Before starting a movie, the team was supposed to show news slides. The young man couldn’t find them.

Zhao shut off the projector and apologized to the waiting audience.

“Don’t ever do that again!” Zhao started to scold the young man, but was interrupted by the news announcements that his colleague started playing from a record player.

At last, they found the slides and loaded them. They turned off the record player and put the projector on. Hand-drawn and handwritten bits of news flickered on screen. They detailed the feats of a skilled farmer from another village.

Part of Zhao’s work was to collect stories of model farmers and share them with other villages. The unit used a special pen to draw and write the stories on the slides themselves.

When the news slides were over, Zhao picked up the first movie reel, loaded the film carefully and waited for the crowd to calm down.

“Good evening, comrades. Tonight we are showing one of the eight model operas, The Taking of Tiger Mountain,’” he announced into a microphone. His voice bellowed from a speaker hanging from a pole that held up the screen.

The “eight model operas” were sanctioned entertainment during the Cultural Revolution, based on traditional Peking Opera but infused with revolutionary spirit. They feature a lot of flag waving and soldiers shouting slogans; enemies of the revolution were usually crushed to the sounds of erhu (a traditional two-string Chinese instrument) and gongs.

The crowd cheered. Zhao marched back to the projector and, teasing the audience, waited a moment before flicking the switch. As the screen brightened to life, the villagers broke into chatter. They knew the story. It had been played in that clearing many times before, but they still gossiped about the characters.

Years after his promotion, Zhao, no longer the movie man, would take his young daughter on special outings to join in the fun of village screenings. By 1984, there were 120,000 mobile cinema units in China. They reached 97 percent of the population. Although their numbers have declined since the 1990s, films are still shown in public spaces to this day. One of Zhao’s team members never left the job. He now plays films to villages once a month on a digital screen.

This is a story from our archives: It was originally published in March 2011 in our issue “Lights, Camera, Action,” and has been lightly edited and updated. Check out our online store for more issues you can buy!