From jail sentences to mandatory government mixers, here’s how ancient Chinese tried to marry off their sons and daughters

For many young people in China, marriage can be a chore rather than a choice. Between matchmaking services, endless dating shows, parental marriage markets, and social stigmas against single or “leftover” women, Chinese society is obsessed with seeing its youth wedded as soon as possible.

But the truth is, young people today have it lucky compared to ancient China, when parents determined to marry off their children at the conventional “marriageable” age could appeal to official channels–including government-mandated mixers, laws, and even criminal persecution.

For much of Chinese history, strict social mores regulated and restricted interactions between the sexes. During the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 467 BC), an occasion called 仲春会 (literally, “mid-spring meeting”) was specially set aside for youngsters to mix and find their destined match. According to the Rites of the Zhou Dynasty, this party was held in various localities on the second month of spring each year, and even had a theme, 奔, meaning “to go with your beloved person.”

Sounds like a zany bacchanalia of young springtime love? Not really. This event was actually organized by local governments, on pain of prosecution: “Anyone who doesn’t take part in the meeting for no reason will be punished.” (无故而不用令者,罚之。). At least these days, when your parents go splashing your personal info all over Tiantan Park in Beijing, you’re allowed to hide at home in embarrassment.

Being forced to attend a party may not be the worst fate in the world. But things get hairier still if you didn’t get married before a certain age. In the southern kingdom of Yue, the parents of “spinsters” older than 17 or bachelors over 20 could be charged as criminals. When it came to the Han (202 BC – 220 AD), unmarried women under 30 would be taxed five times higher than married women. The ancient Chinese knew, just as we do now, that parental guilt and tax relief are at the core of the institution of marriage.

In the reign of Emperor Wu of the Western Jin Dynasty (265-316 AD), the government dispensed with mixers and punitive measures. Instead, they would send a spouse directly. Back then, as now, the Jins targeted females. According to the History of the Jin Dynasty, in 273, Emperor Wu regulated that “If parents didn’t find a husband for their daughter beyond 17, the local government would arrange a man for her.” (制女年十七父母不嫁者,使长吏配之。)

The mechanics of how they would choose a suitable man are not discussed. Some policymakers in the later Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589) seemed to have felt this was too much effort compared to the threat of jail: One regulation, recorded in the History of the Song Kingdom, stated that “if a woman didn’t get married after age 15, her whole family would be sent to prison.” (“女子十五不嫁,家人坐之”。)

Don’t you feel lucky to be living in modern China, single millennials? Sure, you may be “leftover” at 27, hassled by nagging relatives and a constant barrage of media questioning your self-worth, have to suffer blind date after blind date, and condescending advice from married acquaintances—but at least you don’t have to eat prison food.

For an in-depth look at on social pressures on modern Chinese people to find a partner, check out the report from our weekend visit to Beijing’s biggest “marriage market.”

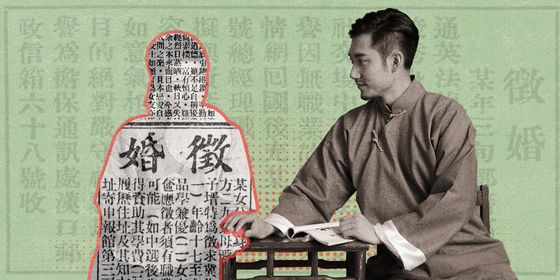

Cover image from dlblhs.com