Disturbing “missed connections” video exposes a lack of stalking protection

“If I can’t use normal channels, I’ll [find her] some other way,” Mr. Sun vowed to the camera, alarming millions of viewers who’ve followed the story of his obsession with a fellow shopper at a Beijing bookstore via a series of viral Pear Video clips since mid-December.

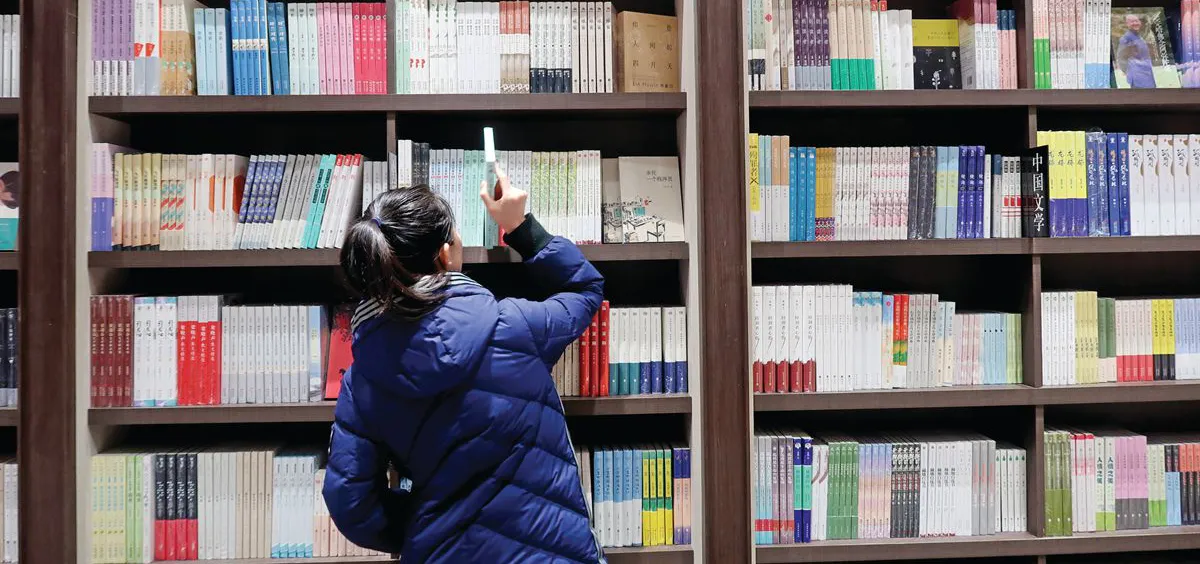

Sun, who is only identified by his surname, had visited a Wangfujing Bookstore before last year’s Mid-Autumn Festival and “fallen in love at first sight” with a female customer. Having failed to talk to her at the time, Sun quit his job and began loitering at the store from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. for 50 consecutive days. When his target failed to materialize, he tried suing her for an unspecified offense at the Dongcheng District People’s Court (which didn’t accept the suit) to get her attention.

Chinese media has since dissected the story from every angle—is Sun mentally ill? Was it a publicity stunt for some product?—but the most disturbing aspect is the gaps it exposed in privacy protections. Several reports have compared Sun to Masaru Iyogi, the 46-year-old man arrested by Tokyo police in June of last year for pursuing a woman he’d “fallen for” at a gas station—by loitering outside her house, placing silent phone calls, and digging through her trash for over 20 years.

Both Iyogi and Sun have told their respective publics that they’d “get peace of mind if only [they] can see her.” Japan’s Stalker Control Law, introduced in 2000 following the murder of a college student by her stalker, criminalizes both “pursuit”—actions that originate from unrequited romantic feelings—and stalking, or repeated acts of pursuit that threaten the safety of the victim. Should the target file a criminal complaint, the perpetrator may receive (in order of escalation) a warning, a restraining order, or a year in prison.

By comparison, the closest equivalent article in Chinese law criminalizes only actions such as spying, disseminating others’ personal information, and taking photos without others’ knowledge, which may lead to five to ten days’ detention or a fine of under 500 RMB. As of 2011, victims can be awarded a court injunction against the perpetrator, but in Sun’s case, no crime has technically been committed, and his victim is unlikely to risk revealing herself by taking action.

All eyes are now on the draft of China’s planned sexual harassment law, scheduled to go before the National People’s Congress in March. Though the new legislation will mostly deal with how complaints are handled in the workplace, it will, for the first time, include a definition of harassment in both action and word, and make it an offense liable for civil action. For the moment, China faces a “missed connections” campaign that will hopefully not gain traction on social media.

Stranger Danger is a story from our issue, “Home Bound.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.