The events that most shocked, impressed, or outraged the internet from January to December

“2020 has not been a peaceful year,” goes a phrase commonly bandied on the internet in China this year. Whether they chalk this up to a supernatural “gengzi” cycle (a once-in-60-years occurrence in the Chinese calendar when disasters supposedly reign), or just coincidence, it’s clear that the year that Covid-19 became a global pandemic and natural disasters ravaged southern China was no ordinary one for the headlines.

Throughout the year, TWOC has tried to keep up with the events and trends that riveted China in our Viral Week series and other content, providing context to occurrences ranging from pandemic control to “period shaming.” Here, we summarize the top items that lit up our WeChat, Weibo, and mainstream news feeds in each month of the year:

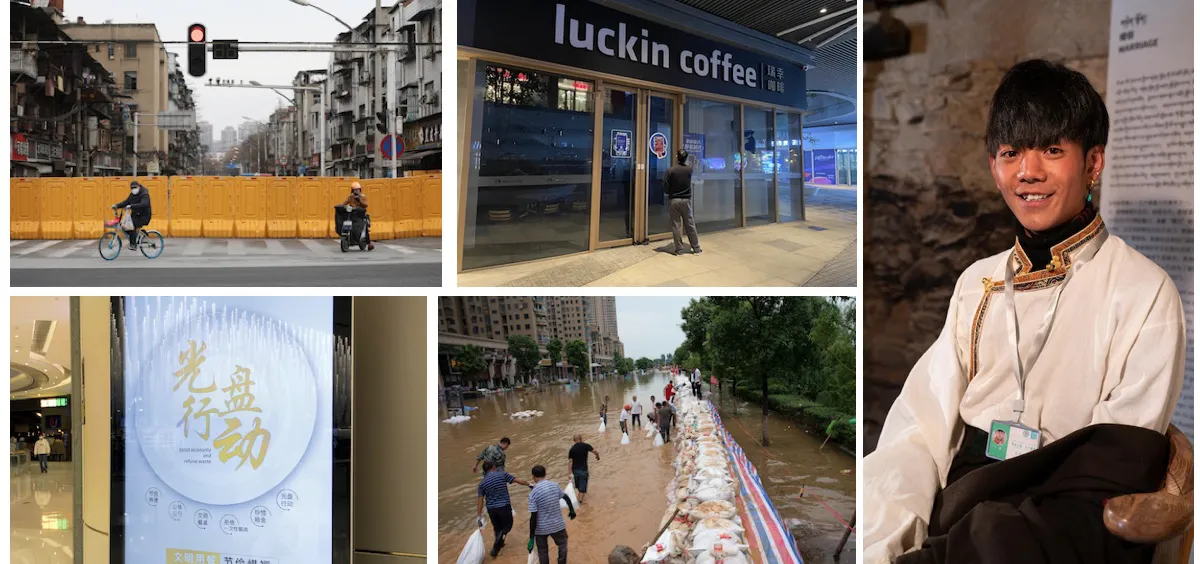

January: Covid-19 and lockdown of Wuhan

(VCG)

Though there had been news of “pneumonia of unknown cause” in the city of Wuhan since December 2019, few recognized the seriousness of the disease, as it was reported in early January that eight people had been punished for spreading “false rumors” about the outbreak. But after renowned respiratory expert Dr. Zhong Nanshan publicly confirmed human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus on January 20, China’s response kicked into high gear: Wuhan shut down transportation out of the city just ahead of Chinese New Year on January 23, and other cities followed suit with their own “lockdown” measures.

February: Mounting infections and Dr. Li Wenliang’s death

(VCG)

Over a billion Chinese spent their Spring Festival holidays in at home, watching news of mounting Covid-19 infection rates, overloaded hospitals, heroic relief workers, and mask shortages. They were heartened by the rapid completion of emergency hospitals Huoshenshan and Leishenshan on the outskirts of Wuhan, and devastated by the death of ophthalmologist Dr. Li Wenliang, one of the eight reprimanded in January for “spreading rumors,” due to Covid-19.

March: Xiao Zhan’s fandom

(VCG)

Most Chinese netizens accept over-enthusiastic fans, who crusade on behalf of their favorite celebrity online and attack perceived “haters,” as an unfortunate fact of life on the internet. However, many felt that the fanquan (饭圈, “fan circle”) of actor Xiao Zhan went too far when they complained to China’s cyber-authorities about a fan-fiction story that portrayed their idol as a cross-dressing prostitute, leading the web portal Archive of Our Own to be blocked on the mainland. The halfhearted apology from the actor’s studio on March 1 also ignited debate on the extent to which celebrities are responsible for their fans’ behavior.

April: Sexual assault case in Yantai and Luckin cooks the books

(VCG)

Allegations that Shandong executive Bao Yuming had been raping his underage adopted daughter for three years, and that police in Yantai and Beijing repeated ignored the girl’s requests for help, broke on Weibo on April 7. The Supreme People’s Procuracurate sent a team to investigate the matter, but concluded in September that there was insufficient evidence to charge Bao with sexually assaulting a minor, as the girl’s parents had changed her age on official records and she had been over 18 at the start of her relationship with Bao, rather than 14 as she claimed. Bao, who illegally held dual citizenship in China and the US, has been deported, and his license to practice law has been revoked.

Luckin Coffee, the Chinese “new retail” chain that had vowed to take on Starbucks in the domestic market, was found to have faked around 2.2 billion RMB’s worth of revenue in its 2019 annual report and have understated its costs and losses. The company has not admitted to or denied the charges, but has agreed to pay a fine of 180 million USD to the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Luckin’s coffee-order app also crashed in the days due to customers rushing to redeem their coupons after the scandal broke on April 2.

May: Gaokao identity theft

(VCG)

On May 24, a woman named Chen Chunxiu discovered that her results from the National College Entrance Exam (gaokao) had been suppressed 16 years ago, and an impostor attended and graduated from the Shandong University of Technology in her place. The following month, several people came forward with similar stories, prompting an investigation by Shandong authorities. Since 2018, 242 cases of identity theft in college admissions have been detected in the province, all taking place before 2006. In response to the incidents, Shandong employed facial recognition technology for the gaokao in July.

June: Covid’s return and “positive energy”

(VCG)

After 56 infection-free days, a new locally transmitted case of Covid-19 was diagnosed in Xicheng district of Beijing and was soon connected with the Xinfadi Wholesale Market. The discovery of the virus on salmon-cutting equipment at the market led to closer scrutiny of cold-chain storage as a means of transmitting Covid-19, and Beijing’s response—closing down and testing relevant communities, and assigning risk levels to different neighborhoods—set an example for how a city can contain a localized outbreak.

A fifth-grader from Jiangsu province committed suicide after her teacher criticized her school composition for not transmitting enough “positive energy,” leading to debates on the misuse of the term and the immense psychological pressure on students. Around the same time, a 13-year-old boy from Heilongjiang province, who went viral for his spot-on imitations of grumpy teachers, took down his videos amid criticism for not being “positive” enough, sparking further discussion on the boundaries of public expression.

July: Record-breaking floods

(VCG)

June and July saw record-breaking rainfall and the worst flooding since 1998 across much of southern China. Poyang Lake in Jiangxi province, China’s largest freshwater lake, reached its highest recorded water level in history on July 12. The floods displaced over 4 million people in 24 provinces and regions, with over 200 dead or missing.

August: Period poverty and empty plates

(VCG)

Grainy photos of unpackaged sanitary pads, sold at 21.99 RMB for 100 pieces, attracted mockery from netizens before several pointed out that unbranded, low quality, and knockoff menstrual products may be the only option for low-income women. Discussions of “period poverty” for the remainder of the month focused on the unaffordability of sanitary products and the stigma that still surrounds menstruation among older women and in rural areas. In October, a college student in Shanghai faced support as well as backlash for placing “pad-sharing” boxes in conspicuous locations around campus.

On August 11, President Xi Jinping launched the latest round of China’s “Operation Empty Plate” to reduce food waste and improve the nation’s food security. Different parts of China have put their own spin on the campaign. Several cities suggested that diners order one dish less than the number of their party when going out to eat. An overzealous restaurant in Changsha asked customers to weigh themselves before entry to get food recommendations, and a high school in Hunan province attempted to fine students for not finishing their food.

September: Food delivery workers

(VCG)

A ten-month investigation by People magazine revealed the cutthroat competition and harsh working conditions of China’s takeout sector, with drivers facing fines and forced to break traffic laws to meet ever-tightening delivery deadlines. The lackluster response by delivery apps Eleme and Meituan also sparked outrage—in particular, Eleme’s “Will you give me five more minutes?” campaign, which encouraged customers to extend the delivery time on their orders, was perceived as a way of pushing responsibility onto the consumer.

October: Fake socialites

(VCG)

WeChat account LIZHONGER published screenshots from a group chat called “Shanghai Socialites,” where members discuss strategies to “group buy” afternoon tea for two at the Ritz in parties of six (without eating the food), or rent out rooms at luxury hotels in parties of up to 40—all for the purpose of taking photos and posing as high-end consumers on social media. The ensuing response in mainstream and social media showed a mix of opinions, with some of the women and their supporters defending their right to spend their money however they want, and others lamenting their relentless materialism.

November: Tibetan heartthrob

(VCG)

Tenzin, also known as Dingzhen in Chinese, is a 20-year-old Tibetan farmer who became an internet sensation from a 10-second video showing him smiling and walking. A Weibo hashtag bearing Tenzin’s name had been viewed over 1 billion times just days later, with netizens praising the young man for his good looks and “pure” air. Tenzin, who never went to school as a child, has been offered the job of a tourism ambassador in his home county of Litang, Sichuan province, and recently participated in a TV fashion show.

December: #MeToo

(VCG)

The sexual harassment lawsuit against television host Zhu Jun opened for its first hearing on December 2 in Beijing. The plaintiff, identified as Xianzi, was an intern sent to interview Zhu at state broadcaster CCTV, and brought the suit in 2018. The closed hearing drew a crowd of supporters for Xianzi in outside the courthouse, but Zhu was not present, and the hearing was adjourned with no date set for it to resume.

Correction: An earlier version of this story erroneously dated the Luckin Coffee incident to May

Cover images from VCG