When innocent questions prove to be fatal

“What would you do if the woman sitting next to you and your girlfriend in the cinema asks for help opening a bottle of water?” asked the “2018 Men’s Love Examination,” an online quiz for Chinese males on their suitability as a partner.

Some were confused by the question, innocently wondering why anyone would not agree to help. These people may be too simple, and sometimes naive—at least, according to certain web-savvy men (and women). The question was based on a supposed real-life incident which ignited a national debate in December 2017, after a Weibo user quarreled with her boyfriend due to his agreeing to aid a female stranger. Some felt the stranger was making a bizarre imposition; others thought that no gentleman would refuse such a request.

To help or not, that is the question. With so little consensus, these dilemmas are known as 送命题 (sòngmìngtí, “life-costing” or “fatal” questions), indicating that any answer would cause problems. It might be a twist on 送分题 (sòngfēntí, grade-gifting questions), a term widely used by teachers and students to describe easy exam questions that effectively “gift” points to the test-taker.

The expression first went viral online in 2016, when students at a Hubei university were assigned an 800-word essay on “Why do you (not) have a girlfriend/boyfriend?” as summer homework. One respondent, caught between the humiliation of having to explain his romantic failures and his desire to pass the class, exclaimed, “What a fatal question!’”

Actually, perilous catch-22s have existed for centuries. Wives asking their husbands “If your mother and I fall into a river at the same time, who would you rescue first?” (如果我和你妈同时掉河里,你先救谁?Rúguǒ wǒ hé nǐ mā tóngshí diào hélǐ, nǐ xiān jiù shéi?) is widely believed to be the first—or at least the most hackneyed—example of a loaded question in the Chinese language: It has over 2.27 million search results on Baidu with no consensus on an optimal answer. One urban legend claims that a mother-in-law skipped her daily square-dance session to learn swimming, just to set her son’s mind at ease.

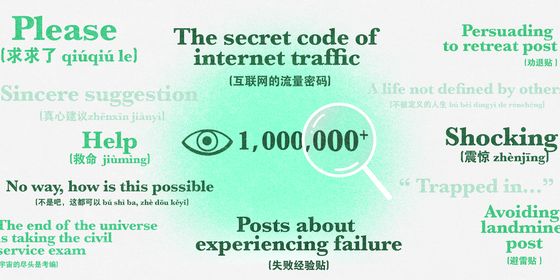

Fatal questions have since evolved to sound more innocuous, thus more sophisticated. A woman might ask her boyfriend:

When I was taking my medicine earlier, guess what I saw?

Nǐ cāi, wǒ gāngcái chīyào de shíhou kàndào le shénme?

你猜,我刚才吃药的时候看到了什么?

Woe betide the swain who actually tries to guess, instead of crying:

Honey, what’s wrong? Why did you need medicine?

Bǎobèi, nǐ zěnme le? Wèi shéme yào chīyào?

宝贝,你怎么了?为什么要吃药?

Negotiating such conversational landmines requires the ability to intuit danger and think several steps ahead to protect oneself—or 求生欲 (qiúshēngyù, “survival instinct”). Therefore, “life-costing questions” are also known as “survival instinct tests.”

The government is in a position of power to suggest some of the deadliest conundrums. In 2017, after the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television prohibited actors from appearing on variety shows with dyed hair, many celebrities flocked to the hairdresser’s to dye their locks back to a natural color. Just to be safe, though, one TV station edited black hair onto their stars’ heads, prompting netizens to exclaim, “What extreme survival instinct!” (求生欲太强了!Qiúshēngyù tài qiáng le!)

So what’s a person with strong survival instincts supposed to do at the cinema? Take the bottle, hand it to his girlfriend, and say: “Honey, can you open it for her? If you can’t, I will help you.”

Cruel Conundrums is a story from our issue, “China Chic.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.