The empty monuments to China’s rural building boom

For the curators of world-class museums, it’s always a heachache to figure out which of their collections to display within a limited space, and which to relegate to storage.

Not so in China, where curators have the opposite issue. As the country builds museums at a breakneck speed, some struggling to find anything to exhibit at all.

In January, a seven-floor museum designed by Burj Khalifa architect Marshall Strabala, became the fourth to open in the “international garden city” of Changxing, Zhejiang, in just three years. The desert city of Ordos has erected a vast bean-shaped museum, a library resembling a bookshelf, and an elaborate opera house. Shanghai is in such a hurry, it opened the 600,000 square feet China Art Museum on the same day as the Tate Modern-like Power Station of Art.

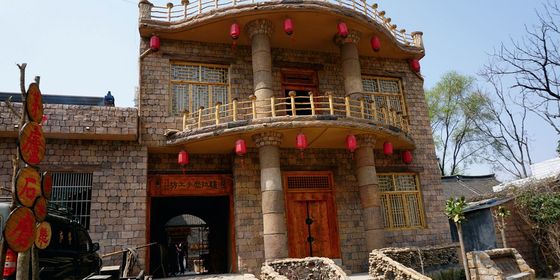

The Red Brick Contemporary Art Museum: good for photos, not so much for exhibits (VCG)

In Meixihu, Changsha, a typically mind-melting Zaha Hadid-designed museum has been expensively unveiled to a largely indifferent public. Meanwhile in Beijing, the Red Brick Contemporary Art Museum, erected in 2017 in remote Hegezhuang village, features seven air-conditioned halls so empty of exhibits it has been compared to “walking into an empty Olympic swimming pool.”

These are just some of the remarkable—and remarkably vacant—monuments to art and culture that have sprung up all over the country in the last few years. The pace and magnitude of this building boom may be unprecedented: China had just 25 museums in 1949. This had risen to 349 museums by 1978, and now there are well over 5,000, according to the National Cultural Heritage Administration, together attracting around a billion visits a year.

By 2020, the administration’s current five-year plan aims to have at least one museum for every 250,000 people. The ambitious plan still lags far behind the US, which has around 35,000 museums, but its scope is still beyond the necessity or even ability of those building and running these museums.

Shanghai’s China Art Museum was converted from the China Pavilion of the 2010 World Expo (VCG)

Jeffrey Johnson, who runs Columbia University’s China Megacities Lab, has been a consistent critic of the “museumification” aspect of China’s rapid urbanization. He argues that local governments tend to erect multiple museums, hoping to spur into life a cultural identity for their cities, but that the pace of museum building far exceeds demand. Curators struggle to fill them with either exhibits or audiences, and many are not even open. “They might have a grand opening…but if you return to this museum, which officially has been open for three months, it…might be closed and locked.”

Meanwhile, local governments are responding to the five-year plan. In Kunming, for example, each county must have two museums by 2025—a well-meaning strategy that intends to invigorate tourism, urban renewal, and cultural cachet in an underdeveloped region. Absent good planning and curatorial expertise, though, such policies end up producing poorly designed white elephants that benefit only the careers of the officials who proposed them.

“In my research, I have visited many museums independently where I have had to ask the staff to follow me so they can turn on the lights and multimedia installations for me,” Leksa Lee, China studies professor at New York University – Shanghai, told the SCMP. “Not every county has enough cultural and historical resources to be exhibited.”

However, since land development projects have become most Chinese cities’ main revenue stream, they have an incentive to continue funding an endless cycle of new construction. These are often crowned with an iconic cultural landmark (such as a museum, library, or opera house) so that the municipality can meet national development goals—rebuilding China’s national pride and cultural infrastructure—while making developers foot the bill.

Building a lavish landmark is one thing; running it another. Once developers are done making their money from the commercial or residential projects that came attached, “they don’t really care,” Johnson told Forbes.

China lost a great deal of its art in the last century to invasion, civil war, looting, tomb raiders, overseas sales, and the Cultural Revolution. And while some of these antiquities are finding their way back, “There aren’t enough curators, there’s not enough content,” according to Johnson. “In many cases these are dysfunctional institutions because there’s no one running them..They’re building it because they want to build the tower on the site adjacent to it to make their money.”

Cover image of the Ordos Museum from VCG