Banners and radio spread coronavirus knowledge in the countryside the old-fashioned way

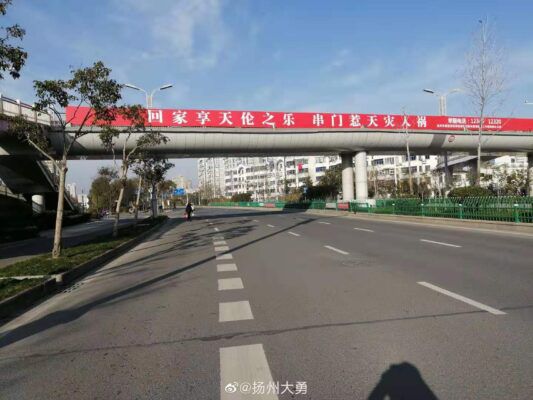

Nowhere does slogans quite like China. Red banners (横幅) exhorting official policies and initiatives are found everywhere from schools to highways, farms to railway stations, and even public toilets.

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (over 40,000 cases of the virus, which originated from Wuhan, had been confirmed at the time of writing), banner producers and slogan writers have worked overtime in an attempt to inform the public of the risks. Some banners, like those below, are forthright to the point of bluntness about the importance of preventative measures:

(“New Year visits bring harm; dining together is a death wish”)

(“Stay home and enjoy family fun; go outside and suffer from man-made disaster”)

(“Visit homes this year, visit graves next year”)

(“Face mask or respirator: It’s your choice”)

Banners are not the only means through which local officials have sought to spread information. In some rural areas, wired public radio is being used to broadcast advice to residents. In Wenzhu village, Henan province, messages encouraging residents to stay indoors, wear face masks, and avoid meeting up for meals have been given an extra twist: they were recorded to the tune of Henan opera Hua Mulan (based on the same legend made famous by the Disney animation). In an interview with Beijing News, Dai Xiulin, the deputy chief of Wenzhu village, suggested that broadcasting in this way helps information reach older residents, who may not use the internet or mobile phones.

While major news outlets have focused their reporting on Wuhan, the epicentre of the outbreak, and other major urban centers, China’s rural regions worry that a major outbreak in the countryside would have equally dire consequences due to inadequate healthcare provision. According to government statistics, China has a rural population of over 500 million. Around 7.2 percent of this group is illiterate, and a high proportion are elderly. Modern methods for spreading information, through text message, WeChat, and other social media, may not be effective with these demographics.

In Xianhe village, Guangdong province, local officials have reported success with slogans and banners that are “in touch with the common people.” One banner, written in a poetic-style, references the local custom of visiting relatives on Xianhe’s traditional day for ancestor worship, which fell on February 5 this year, to encourage villagers not to get together: “I go to your house and you’re nervous; you come to my house and I get flustered. I love you and you love me, so for the moment let’s not visit each other.”

Local Party secretary Lu Weirong told Chaozhou Television that the banner was “easy to understand, down to earth, and touches people’s hearts…as soon as everyone sees it they understand naturally.” Lu also claimed that after putting up the banner, the number of those entering the village from outside fell by 95 percent.

However, Henan province has been labelled the capital of “hardcore slogans” by some netizens. One hard-hitting banner in Hebi city was aimed at those visiting their relatives during the lunar new year holiday: “Bring the virus back to the village and you’re not a filial child, infecting your parents is utterly heartless.” More controversial than these propaganda campaigns have been reports of villagers physically blocking roads into their communities, and of overzealous officials refusing people entry to their own homes.

One Weibo user described the disease prevention work in Henan as like a rockslide: ruthless and rapid. Such ruthless attitude to the spread of sensible information, rather than of irrational and punitive measures born of panic, will be vital to preventing further spread of the virus.

Cover Image from VCG