Derek Sandhaus’s new book is a romp through Chinese drinking history and culture

“A journey of a thousand drinks begins with a single sip,” writes Derek Sandhaus in Drunk in China: Baijiu and the World’s Oldest Drinking Culture. For Sandhaus, that first sip of baijiu, China’s notorious tipple, did not go down well at all.

“It smelled as if someone had run a garbage bag of soiled gym shorts into a bucket of fish sauce, stirred in an equal measure of Drano, rotten fruit, and blue cheese, and left to marinate a few days. It was a smell conjured from the pits of hell, the last whiff one senses before waking up in a serial killer’s rumpus room.”

Never let it be denied that Mr. Sandhaus has a particular gift for descriptive metaphor.

Fortunately for us all, Sandhaus did not stop with that first shot of Chengdu hooch. Like the apostle Paul struck blind on the road to Damascus (a possible hazard when lustily researching spirits around China), he proves there is no zealot like the convert. Drunk in China is equal measure riotous epistle to the baijiu non-believer and a drinker’s diary.

We join Sandhaus on his boozy journey of discovery as he travels from rural distilleries to high-end Shanghai cocktail lounges and a Chinese-language Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in Sichuan. The book also delves into China’s fermented past and a history of alcohol production in this part of the world that dates back to neolithic times. It would seem that in China, as in other parts of the world, settled agriculture may have resulted as much from humanity’s pursuit of a steady buzz as from the search for the ingredients for a decent bread or Chinese bing.

Sandhaus spends a considerable amount of time correcting a large number of common misconceptions about China’s unofficial national drink. First, baijiu is not a single spirit but an entire category of drinks as different in process and palate as vodka is from tequila. There is also baijiu‘s reputation as a harsh, potentially toxic beverage which, in the wrong hands, might taste like something akin to “Jolly Ranchers melted in paint thinner.” (Sandhaus displaying his gift for metaphor again.)

Cultural context matters, he argues, especially when trying something new. He asks us to imagine the reaction of a first-time whiskey drinker if they were initiated into the world of brown liquors by being forced to drink an entire bottle of peaty Islay scotch in a single sitting. The point is that baijiu appreciation in China is a multiverse of flavors and fetishization to rival any of its Western equivalents, from wine snobs to bourbon bros.

The book also suggests that more insidious forces may be at play here. Westerners have a long and unfortunate history of viewing Asia in general, and China in particular, as an exotic and possibly dangerous other. For many centuries, Chinese food has gone through cycles of mistrust (bat meat soup, anyone?) and prejudice abroad.

But if baijiu remains something of a tough sell internationally, it is an integral, if oft-lamented, part of Chinese hospitality and business culture. The fragrant aroma is an almost indispensable part of any good Chinese meal, especially the spicy and sour cuisines of the south, where the best baijiu is made in Sandhaus’ opinion.

“When one consumes boiled beef in a sizzling sea of chili oil with a carafe of Wuliangye, she gets the full flavor complement. Without baijiu, the meal is like listening to your favorite album with the bass muted—a good thing rendered strange by omission.”

It is a cliche, although no less accurate for being so, that sometimes the best way to learn about a place is through the slightly warped view found at the bottom of a glass. Sandhaus’ misadventures in pursuit of his ethanol epiphanies, some previously recorded on his research blog “300 Shots to Greatness,” are classic anecdotes that will be fascinating to readers abroad. Those with more experience in China may nod along while mentally recounting a few hazy baijiu misadventures of their own.

While there’s no reason to doubt Sandhaus’ enthusiasm or his research, it is worth noting that he is also an investor in a baijiu distillery in Sichuan. If his aim is to encourage greater consumption of the fiery booze, his enthusiastic writing and raucous tales are likely to do the trick.

The book also comes complete with recipes for baijiu cocktails crafted by intrepid bartenders around the world including former Beijing bar legend Paul Mathew. But of all the sours and swizzles, it is the book’s final recipe, “The shot of baijiu,” that rings truest for the appreciation of Chinese spirits, :

“Traditional recipe: Fill your neighbors’ glass to the brim with baijiu and allow them to return the favor. Serve neat at room temperature in a small cup, preferably alongside food. Consume in one swig following a well-considered toast. Repeat ad nauseam.”

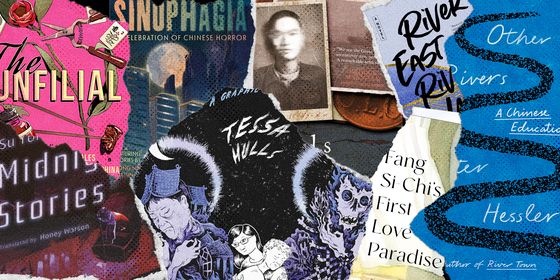

Cover image from VCG