At Beijing’s Changpuhe Park, hundreds of elderly Chinese have been looking for a partner for company, sex, and mutual care, but few succeed

“An apartment is a must,” a man in his late 60s emphasizes to several of his male peers at Changpuhe Park in Beijing’s Dongcheng district on a Saturday morning, citing a common requirement for marriage in China.

But they are not talking about their children, whose generation’s anxieties about marriage—and the seeming impossibility of affording it—is a well-reported phenomenon in Chinese society today. Rather, these uncles are sharing their own stories of successful and failed dates. They hope to find themselves a partner at this very park, one of Beijing’s most popular xiangqin (相亲, matchmaking) sites for divorced, widowed, or unmarried city residents aged between 40 and 80.

At around 10 a.m. there are only about a dozen of them in the park. They rapidly fire questions as TWOC’s reporter approaches, “Have you come to xiangqin too? How old are you?” One woman, who guesses that TWOC is too young to be looking for a partner among her peers, suggests we instead go to Zhongshan Park, a spot well-known for hosting a matchmaking corner (相亲角) for young singles in their 20s or 30s (or rather, parents who attend on their behalf). Most, though, become reticent after knowing TWOC is here as reporters, and refuse to answer questions.

Two men sitting on a bench explain their refusal: “Who would want to have their photos taken in secret and shared online?” offers one. Another claims: “Some women are just here for money. They ask for millions of yuan from a potential partner. How would they tell you about their true feelings?” Apparently probing outsiders, who may come only for a taste of “novelty” as reported online, are not welcomed by many here.

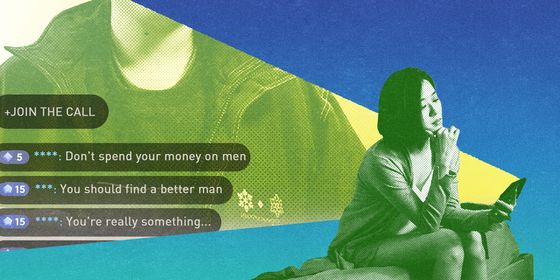

Changpuhe Park and the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, Zhongshan Park in Wuhan, and Haipohe Park in Qingdao are just some of the spots that have recently gone viral for their population of twilight romance-seekers. They have attracted a surge of attention from both the media and general public, especially after several dating shows featuring middle aged or elderly contestants began airing last year, like Jilin TV’s Love Never Comes Late (《缘来不晚》), Liaoning TV’s The Choice of Love (《爱的选择》), and Heilongjiang TV’s Blind Date and Fall in Love (《相亲相爱》).

Featuring middle-aged and old contestants, going on blind dates and answering questions from potential partners, the shows won over viewers by spotlighting a demographic not usually depicted on TV. Young viewers were sometimes left stunned by the straightforward views of older entrants. “It’s important that the function is there, whether I use it or not,” says one female contestant on Love Never Comes Late, about her sexual needs from a partner. Another woman turns down a date to his face due to his unsatisfactory height and education.

But similar dramas of money, property, age, and sex have been taking place in Changpuhe Park over a decade before they were brought to national attention on TV. Here in the nation’s capital, the multifaceted bargain necessary for a mature union gets more complicated when a local-versus-migrant divide is thrown into the equation.

***

Changpuhe’s matchmaking corner takes place each Tuesday and Saturday, starting slowly in the morning and picking up after lunch. The park is about a ten-minute walk east of Beijing’s landmark Tiananmen Square, and attracts hundreds of middle-aged and elderly visitors from all over the city.

In February, the temperature sits at around minus-5 degrees Celsius with a chance of snow, but this has not dampened the park-goers’ enthusiasm. Starting at noon, dozens of elders dance to disco music at a 20-square-meter open area by the Changpu River, and many more can be found sitting on the benches or standing in twos or threes, exchanging greetings and chatting with passersby.

Opposite this area, on the less-occupied bank of the river, is where the more private and in-depth conversations happen. Potential couples move there after exchanging background information (or dance moves) and have deemed the other partner satisfactory.

However, most will reappear on the busy bank after these private conversations. “The success rate is low. Less than two out of 100 pairs turn into a couple,” 84-year-old Xue Lingzhi estimates to TWOC. “To find a partner for people over 50 is far more complicated than for the young.”

According to China’s sixth national census, which took place in 2010, China had over 47 million widowed people over the age of 60, accounting for 27 percent of the senior population. The divorce rate of senior citizens has also doubled over the last 30 years. AgeClub, a consulting and incubation service platform for the elderly care industry, estimated last July that the number of single seniors (including those who were divorced and widowed), at 66 to 79 million, accounting for 25 to 30 percent of the 264 million seniors citizens in China, according to the 2021 census.

“It’s so lonely to be at home, with no one to talk to, and no sound except the TV set,” a retired painter and lecturer, surnamed Zhang, explains to TWOC why he has been coming to Changpuhe Park since he learned about the place over a year ago. The 75-year-old has lived by himself since his wife’s death nine years ago, while his married son lives with his family in another part of the city.

Gu Xiong (pseudonym), who is willing to talk with TWOC without revealing his true name and age, agrees, believing senior people’s psychological needs are often neglected, despite improved living conditions. “One cannot be satisfied with three meals a day and waiting for death,” he says. “Regardless of their age, people have the needs of recreation and communicating with others.”

Some seniors’ interest in a partner is more practical. For example, Xue, who has been widowed for six years, says he wants a partner for “mutual care.” His five children are all busy with their own jobs and lives, and he’d like someone to look after him if he gets sick—of course, he’d do the same for his partner.

According to the fourth “Sample Survey on the Living Conditions of the Elderly in Urban and Rural China,” jointly organized by China National Committee on Aging, the Ministry of Civil Affairs, and the Ministry of Finance in 2015, there were over 100 million “empty-nest elderly (空巢老人)” in China: namely, people over 60 who are either childless and single, who live in a different city from their children, or are living separately from their children in the same city.

The traditional Chinese family structure, as indicated in the idiom 四世同堂 (“four generations under one roof”), where the elderly live with their adult offspring and are cared for by them, has been gradually disintegrating as China urbanizes. Even seniors living together with their children and grandchildren can feel neglected. Gu, who lives with his son’s nuclear family, blames society for giving young people too much pressure. “My son is too busy to pay attention [to me], and even my grandson has to stay up as late as 11 p.m. to finish his homework,” he complains.

Meanwhile, the 2015 survey found over 90 percent of the elderly population prefer to live at home rather than nursing homes, the number and quality of which is still insufficient to meet demand in China.

Desire for sex is also one of the major motivations, admits Gu in a much-lowered voice, seemingly ashamed of the idea. According to a 2013 survey by online dating service Jiayuan.com, around 34 percent of the middle-aged and elderly users of the platform desired sex.

Many regulars at Changpuhe claim to have experienced or heard about one-night stands through the matchmaking corner. A 64-year-old canteen worker surnamed Liu tells TWOC that he’d been approached several times in the park with sexual propositions, and knows some of the regulars in the hookup scene here.

Even after screening out seekers of casual encounters and, allegedly, people who date simply for money or expensive gifts, those who come to Changpuhe with a clear goal of finding a partner—whom Xue optimistically believes to constitute 80-90 percent of park-goers there—have a hard time finding “the one.”

“I’ve come to the park over 300 times, but still haven’t found the right match,” Zhang claims. He had not expected this, as he is offering his potential partner a place to live in his Beijing apartment alongside him and would cover all living expenses, as long as she does not demand any share of ownership of his apartment—the only requirement his son put forward.

However, most of the women he has dated, who are in their late 40s or early 50s, have come to Beijing from other parts of the country and want to marry, which means they would be entitled to a share of the apartment’s ownership along with Zhang’s son after he dies, under China’s current Marriage Law.

Cohabitation without marriage is almost common sense among China’s senior singles community today. A survey by Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in the early 2000s showed that about 80 percent of widowed seniors hoped to “remarry,” but less than 10 percent said they’d register their marriage with the government.

Xue is pickier about his partner: no marriage, no non-locals, and shared living expenses, though he’s willing to contribute a greater proportion than his partner. “I’m looking for a Beijing local, with pension and medical insurance…and good personality, [all of] which may take at least three to five months to find out.” Several of Xue’s “relationships” ended after the first or second meeting, after he found the woman was not in fact a Beijing local, sometimes by asking to see her ID card.

According to Xue, the majority of the women in the park are not locals. A 2017 report by the National Health and Family Planning Commission showed that about 18 million senior citizens have left their hometowns for more economically developed cities like Beijing, seeking jobs and to support their children.

Often middle-aged and elderly women come to Beijing either to find manual work, like in the domestic services industry, or to look after their grandchildren. Usually they have no apartment of their own in the city and no means of supporting themselves without working. Due to China’s household registration system, even the retirees who receive a pension and medical insurance back in their hometown could face high medical expenses if they get sick in Beijing, because their insurance would not be accessible here.

Zhang is still active in the park each Tuesday and Saturday, and spends another one or two days each week with a “steady” date whom he has been seeing for a year—a 75-year-old local woman who is wealthier than him, lives in a villa, and pays more of the bills than him when they go out together to parks and other attractions around the city. He likes her, but thinks she’s “too old.”

According to Zhang, the lady has also been looking for a better match: someone older, because she does not feel comfortable with a younger partner. He explains, speaking for all the elders at the park, “We’re all afraid of being taken advantage of by the others.”

The names of interviewees have been altered for privacy.