Meet the new wave of scholars and translators making the untranslatable relatable

When translated into English, for the past 50 years Chinese poets have been entrusted to the antiquarian. Only the ancients are selected. Their thoughts and feelings are clothed in archaic English, automatically placing them at a distance from the contemporary reader. “There was this idea before that, to make Chinese poetry sound legit, you needed to make it sound like Shakespeare,” Lee Moore, co-host of the popular China Literature Podcast, tells TWOC.

Poetry originally written in a language so far removed from English was seen, for a long time, to be “untranslatable” by a wide variety of prominent figures, including prominent contemporary poet Ha Jin. Today’s two dominant schools of translation formed around this belief—one chased elusive academic faithfulness to the original, with stilted replication of Chinese structures in English. The other took a free-verse approach, that drops any pretense of being faithful to the original.

But Moore says that when we read the original, “A lot of the poetry is approachable and fun.” This relatability is what Tim Clissold tries to draw out in Cloud Chamber, a new collection focusing on seven major poets from the Tang (618 – 907) and Song (960 – 1279) dynasties.

Clissold, a businessman with a background in physics, is modest about his efforts, focusing on the accessibility of this ancient poetry and its applicability to our everyday lives. Once we adjust to the inherent ambiguity of language and form, and take a mediated approach which forgoes attachment to any single fixed meaning, the niche and obscure start to shade into the familiar.

This is just the tip of the iceberg, part of a growing movement toward modernizing Chinese poetry in English translation. “I think the two traditions of handling Chinese classical poetry in English translation are both out of steam,” says Lucas Klein, associate professor of Chinese at Arizona State University. “So I’d like to see something new.” Klein is one of a new breed of Chinese poetry translators, part of a “small community” of publishers, community organizers, academics, and poets. They are trying to strike a balance between being faithful to the original text, while creating poems that stand on their own merits in English, hopefully appealing to the general poetry-reading public.

The rare instances Chinese poetry has tumbled into Western public consciousness remind of how little known it is. In 2021 Elon Musk tweeted “The Quatrain of Seven Steps (七步诗)” from the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280 CE), while Meryl Streep recited The Deer Park (鹿柴) by Tang luminary Wang Wei on Stephen Colbert’s The Late Show in 2020. Both poems were a novelty to their Western audiences, but most Chinese have been able to recite them since pre-school.

Going by Penguin Classics, only Li Bai (李白), Du Fu (杜甫), and Wang Wei (王维) have earned named anthologies, all poets from the High Tang period. But Moore believes these three “are famous not because they are great poets (though they are),” but because "scholars in both China and the West talk about them as a way of discussing the greatness of the Tang.”

In Cloud Chamber, Clissold keeps with tradition by spotlighting Li Bai and Du Fu as well as another Tang poet, Bai Juyi (白居易). That they hold the lion’s share of the anthology is where we see their influence on English literature. Allen Ginsberg greatly admired Bai and wrote “Reading Bai Juyi,” a poem recounting his first month in China in 1984 and following the structure of Bai Juyi's Stopping the Night at Rongyang. Ezra Pound’s Cathay (1915) anthology is problematic for its very loose and Orientalist “translations” of Li Bai, and other Tang poets, but is regarded as a Modernist classic that paved the way for the Beat Generation: To quote Ginsberg’s “Improvisation in Beijing,” “I write poetry because Pound pointed young Western poets to look at Chinese writing word pictures.”

Cloud Chamber focuses its Song Dynasty portion on four poets. If the pithy formulation in Chinese for Tang poetry is "LiDu" (Li Bai/Du Fu), the equivalent for the Song is "SuXin" (Su Shi/Xin Qiji). So it is interesting Xin Qiji (辛弃疾) is mostly passed over here for wild card Mei Yaochen (梅尧臣), a widely recognized figure whose poetry was less culturally significant. Clissold is impressed with the unassuming simplicity and prosaic fodder of Mei’s poetry, sporting titles like "The Ancient Masters Never Wrote a Poem about Lice so Why Don't I.”

His lines are rich in earthy humor, clearly easier for contemporary readers to relate to. Take for example this passage, about being bothered by rats at night:

I worry they'll knock the ink stone from the table,

Or gnaw at books on the shelves.

Now my imbecile boy starts mewing like a cat.

Honestly! What a stupid idea.

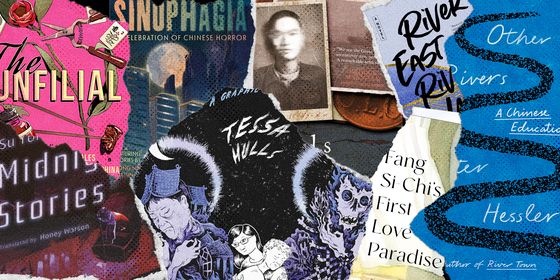

While Song poetry still lags in translation compared to its Tang predecessors, it is as if we've passed an invisible threshold in the past decade, where the profile of Chinese poetry in general has become firmly planted. Publishers have begun to mine the Tang for more outré choices. The New York Review of Books (NYRB) put out a selection from the "poet of illicit love" Li Shangyin (李商隐), China's answer to the ancient Persian poet Rumi, known for his love poems in the West. Then there's the "bad boy" of the late Tang, Li He (李贺), touted as a Baudelaire-like figure and back in print for the first time in decades. 2021 saw the first complete translation of the poems of Meng Haoran (孟浩然), another of the High Tang masters.

But modern Chinese poets are finally getting their dues as well. We know Ginsberg respected Bei Dao (北岛), Shu Ting (舒婷), and other members of the so-called Misty Poets (朦胧诗人) of the 1980s. They were an influential group emerging after the Cultural Revolution, their work coalescing around the literary journal Jintian (Today).

But despite many of these poets being based abroad, until just over a decade ago there was no “single authored poetry collection of a poet currently living in the PRC” in English, according to Klein. Zeyphr Press in its Jintian Series of Contemporary Chinese Poetry (named for the journal), overseen by Bei Dao, finally changed this. To date they have published over a dozen volumes, in a cause that has now been taken up by more mainstream presses.

There have been small advancements in bringing the Chinese poets of today into English. Klein's latest translated volume, Bloom & Other Poems by the post-Misty poet Xi Chuan (西川), came out in early July, courtesy of venerable literary publisher New Directions and was reviewed favorably by The Poetry Foundation, arguably the biggest institution working today in ancient and modern poetry. US Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith collaborated in poet Yi Lei’s (伊蕾) posthumous My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree: Selected Poems (2020), which includes the daring work “A Single Woman’s Bedroom” which cemented her reputation on the mainland in 1987. A Summer in the Company of Ghosts: Selected Poems by the third generation (post-Misty) contemporary poet Wang Yin (王银) is due later this year, also out on NYRB press.

The internationalization of English means poets can now have a say in how their work is translated, or even do it themselves. It also means the scene can diversify, several Chinese-born poets recently gaining acclaim for their writing in English. There's Sally Wen Mao, whose Occulus (2019) was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize Finalist and Time Magazine Must-Read Book of 2019, and Shangyang Fang, whose Burying the Mountain (2021) was put out by Copper Canyon Press (a key publisher of new poetry in America, with several Pulitzer Prizes and National Book Awards to its name).

But bear in mind poetry is a niche market. As Klein observed, “it is a question in my mind how broad this field can be. I don't know how many Chinese poets your average English-language poetry reader can handle." But with Cloud Chamber’s publication, and other titles in the pipeline, there’s plenty to fill this niche with.

Full disclosure: Cloud Chamber is published by The Commercial Press, TWOC’s parent company.