How a German tradition from 1803 affects the massage parlors of China today

Whether you find them amusing, annoying or confusing, “broadcast exercises (广播体操),” or radio exercises, are ubiquitous throughout China, and, surprisingly, they are now more prevalent than ever. If you walk past a hair salon, a massage parlor, or a hotel at 9:30 in the morning you can see staff members outside the entrance on the sidewalk, dancing to the music of “My Little Apple” or some other hideous pop song, following a lead dancer of course.

After the dance, they finish up by yelling slogans at the top of their lungs, startling passersby, and, according to some news reports, attracting flying objects from residential buildings overhead. To the uninitiated, it can seem either innocently charming or terrifyingly totalitarian. However, this odd show of worker solidarity dates back at least 100 years.

Such exercises are usually done for the purpose of boosting staff morale, enthusiasm, and solidarity. For those who make a habit of visiting such establishments, the overall experience would seem to suggest that this menagerie of dancing and camaraderie may be in vain; however, the core value of this behavior, rather than taking joy in one’s work, would appear to be a sense of collectivism, loyalty, and, in some people’s opinions, “brainwashing.” Although places like Japan are still famous for this sort of worker exercise, its roots can be found in Germany.

This exercise experienced its primitive beginnings in 1803 via Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the “Father of Gymnastics,” who associated patriotism and unity with his popular workout, well before the invention of the radio. His methods were widely applied to armies and factories for much the same purpose they are used in China today. It wasn’t until the 1880s when, bitterly humiliated by the Opium Wars, China’s intellectuals and educators were looking for Western solutions to reform, strengthen, and heal the country. Their answer came in the form of gymnastics at private schools for boosting the young citizens’ spirits and keep them in good health. As it was a variation of the German military calisthenics, it was called “soldiers’ exercise (兵操),” and was very much in the military style.

In 1925, this practice truly became a “broadcast exercise” when the United States married the concept with radio broadcasts for the first time. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company sponsored a well-received radio exercise program that was practiced by millions. Then, the Japanese government, enthralled by the massive scale of the exercise in the US, embraced it. The Japanese armies spread it wherever they went and took it to regions they occupied during World War II, including Taiwan and northeastern China under the puppet state of Manchukuo.

However, broadcast exercises, with their ingrained value of collectivism, quickly fell out of favor after their short-lived peak. While in the US it retreated in the face of more individualized sports like baseball, the concept was also confronted in China after the New Culture Movement in 1919. Hu Shi (胡适), an influential scholar and educator, campaigned for “naturalist education” and boycotted the cultivation of loyalty to the Kuomingtang Party in schools.

Radio exercises were the opposite of what Hu and his academic colleagues wanted to uphold: it was directed, controlled, and could easily be coupled with political sloganeering and propaganda. In Hu’s words, an ideal young person should, “be free of heart and independent of mind.” As a result of these liberal tendencies and education ideas, in 1919, the China Education Association released a new regulation that suggested “soldiers’ exercise” should be replaced with a variety of sports. In 1922, the Chinese government issued another paper that aborted radio exercises in schools altogether.

Toward the end of Republican Era in China, as far as physical education was concerned, mass broadcast exercises were already on the brink of extinction, while traditional martial arts and the more competitive Western sports were on the rise. In Japan they met with a more sudden death; after Japan’s defeat in 1945, the victorious countries banned the exercise because it was considered too militaristic in nature.

The practice, however, found a new home in the USSR. There, the practice found a haven in Soviet collectivism and soon grew to a scale that rivaled that of Japan before the end of the Second World War. This, in turn, affected China. After the foundation of the PRC, China looked to the Soviet Union, the revered and infallible “Old Big Brother,” in every aspect of social and political life. That, of course, meant the broadcast exercises despised by the intellectuals of the Republic of China were brought back in full swing. In fact, aside from the idea that these exercises could be easily linked with political propaganda, they were cheap, convenient, and did not require any equipment—perfect for the then impoverished China.

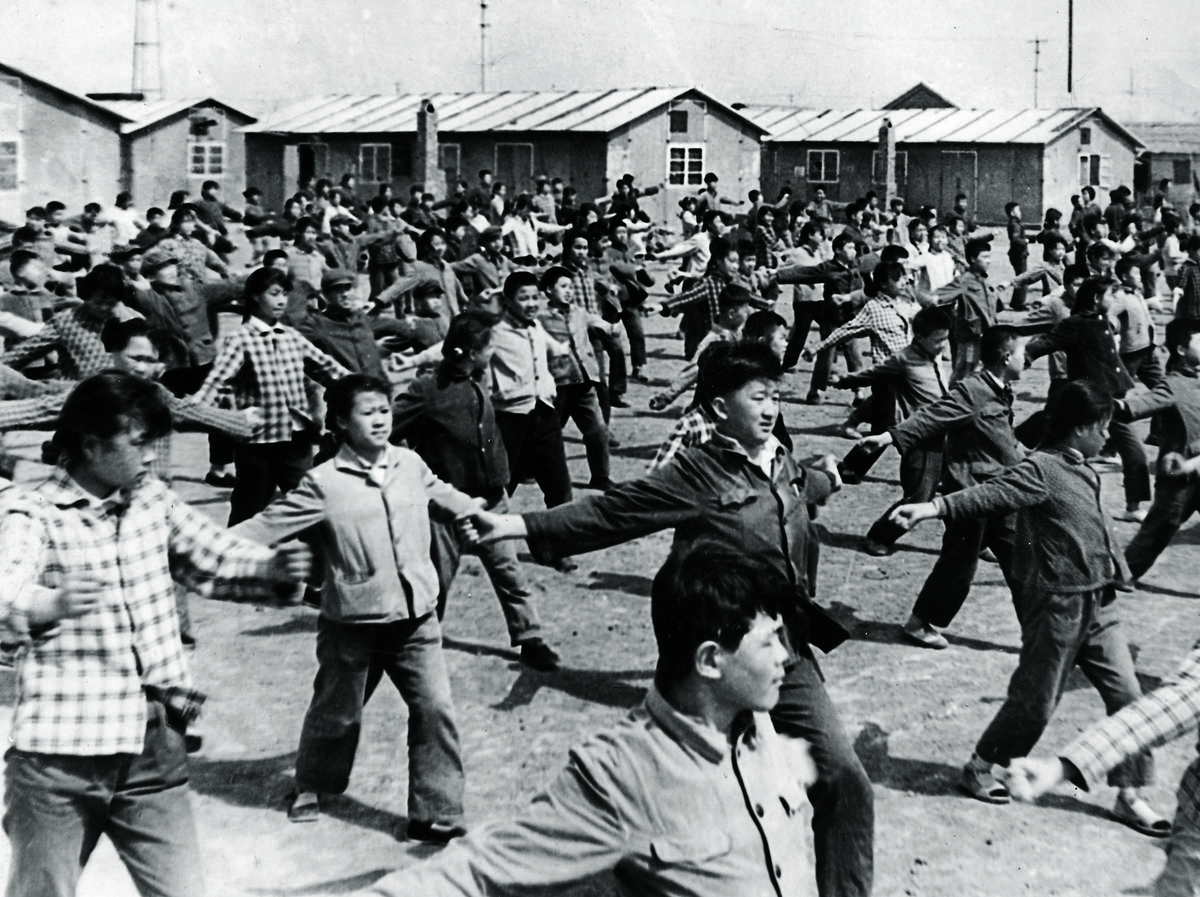

That move officially started a tradition that is still annoying Chinese school kids to this day. In 1951, the China National Sports Association and the Central Broadcast Bureau jointly released the “First Broadcast Exercises.” It was such an event that the People’s Daily published several editorials on the subject, calling for mass enthusiasm and participation. Numerous “Radio Exercise Popularization Committees” were set up all over the country, and a series of 40 stamps were released in 1952 to illustrate the exercises. The workout was carried out for the benefit of “productivity and national defense,” as Zhu De (朱德), the then vice president, put it. The most well-known slogan from that time was, “Everyone should work out. Every day we should go to the exercise ground. We must stay healthy so that we can go on working for our motherland for 50 years!”

It was mandatory for the staff of all schools, governmental sectors, and factories go out to an open ground punctually at the sound of the radio music to practice for ten minutes twice a day. The beginning of the exercise usually featured a quote or a slogan; during the Cultural Revolution, the prelude was “Chairman Mao the Great Leader taught us: popularize physical exercise, strengthen the people’s health, stay alert for enemies, and defend our country!” Even the eye exercises—a minor derivation particularly designed to protect students’ sight in 1963—started with, “Protect our sight for the revolution! Now begins the eye exercise.”

These halcyon days of broadcast exercises have come and gone, relegated to history, but the practice is still going on today—albeit with much improved methodology. Today, Chinese middle school students wouldn’t find the radio exercise posters of the 1950s so unfamiliar; despite changes in China’s political climate, radio exercises have remained in schools, indelibly linked to the curriculum. Much like its heyday 60 years ago, the students participate in it twice every school day—once at the beginning of the day and once around ten in the morning.

Much has changed, even the radios have disappeared, evolving into speakers, iPhones, and the like. The political preludes are gone, morphing into something vaguely related to exercise, such as “the sailing of hope” or “let your dreams fly.”

It’s hard to tell whether the exercise is making the students more spirited, healthy, or united; every school, of course, features youngsters hanging their heads and shoulders, bored and tired, skillfully minimizing their movements to the right degree so that they can both save energy and not be picked on by the teachers sternly overseeing their workout.

From Germany prior to the Napoleonic Wars to the intellectuals of Republican China, right on through to the Cultural Revolution, broadcast exercises have certainly been part of history, and who better to keep this glorious tradition alive than the blank faces of staff members outside a hair salon near you.

This a story from our issue archives. It was originally published in May 2015 in our issue “Startup Kingdom,” and has been lightly edited and updated. Check out our online store for more magazine issues and books you can buy!