Why do Chinese consumers fear additives in their food?

For 36-year-old Jiang Luxiang, every trip to the grocery store involves a lot of counting. “If there are more than three additives [in the ingredient list], then don’t buy it,” the Zhejiang-based health blogger tells TWOC, quoting a teacher from her college nutrition course whose rule for healthy eating she has followed scrupulously for the past 15 years, and even improved on: “Nowadays, I sometimes won’t buy products with more than one kind of additive.”

About five years ago, Jiang also stopped using soy sauce, vinegar, and other condiments with artificial additives, as she believes these products are bad for her health. “Humans should eat foods that occur in nature; that’s the rule of the universe and of nature,” she declares. To her 18,000 followers on lifestyle app Xiaohongshu (RED), Jiang advocates a natural diet consisting of vegetables she picks fresh from farms and cooks in simple ways (such as by steaming or frying in olive oil), coarse cereals like quinoa and yams, and natural condiments like rosemary, cinnamon, and mint. “You eat in order to make your body healthy,” she believes.

Jiang’s methods may be unorthodox, yet the concerns driving them are decidedly mainstream. Last month, well-known soy sauce brand Haitian faced public backlash for allegedly using “inferior” ingredients in its domestic products, compared to those it sells overseas. Customers alleged that the company’s soy sauce sold in Japan only contained natural ingredients, while the same product in China has numerous artificial additives, such as preservatives, artificial sweeteners, and flavor enhancers. At least one of these ingredients, sodium benzoate, has been linked to cancer, reviving public concerns over food safety.

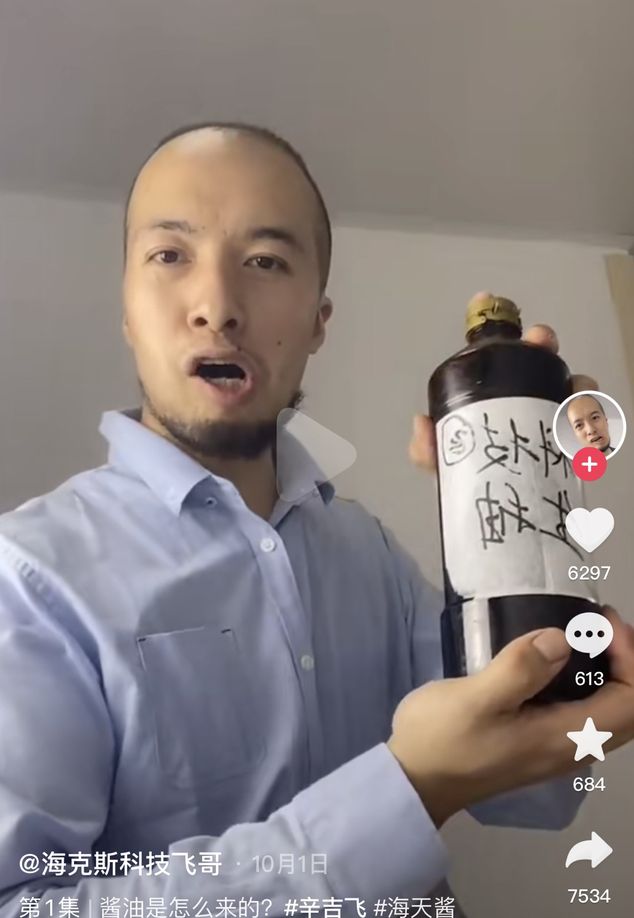

In the aftermath, a viral hashtag related to the controversy accrued 270 million views on Weibo, allegedly started by Xin Jifei, a former food blogger from Liaoning province who had accrued millions of fans on Douyin (China’s version of TikTok) before he deleted his account in September. Xin’s videos exposed the misuse of additives in the food industry, from making fake steak to milk tea without any dairy. In one of his viral videos from last August, Xin showed how one could use sliced chicken, salt, pigment, edible essence, and beef tallow to mimic the flavor of beef jerky.

Used mostly for enhancing flavor and prolonging shelf life, additives are widely used in food products worldwide. Different countries have their own standards for the use of food additives, which was the explanation Haitian gave for the differences in their Japanese and Chinese ingredients. However, as the Chinese public becomes increasingly health-conscious, numerous controversies have erupted in recent years about the use of chemical additives alongside general food safety scandals.

The history of food additives can be traced back over 10,000 years with the discovery of salt, a natural preservative, from evaporated seawater. In the Han dynasty (206 BCE—220 CE), bittern, the liquid remaining after salt is harvested from saline brine, was used as a coagulant to make firm tofu. In the Northern Song dynasty (960—1127), people added nitrite to preserve meat, and potassium alum to make fried bread sticks. In the sixth century, Jia Sixie, a leading agronomist, recorded a method of using leaves as natural pigment to make cold noodles in his book Essential Techniques for the Common People (《齐民要术》), one of China’s oldest agricultural encyclopedias.

Food additives have been widely used in processed foods in China since the late 1990s. At that time, preservatives, sweeteners, pigment, and other chemical food preservatives were sometimes sold in bulk in shops that also carried other chemical products like pesticide, leading many people to view food additives as dangerous or poisonous even today. In 1996, the Ministry of Health (currently the National Health Commission of the PRC) released a set of sanitary standards for food additives, outlining the types of additives permitted and the appropriate dosage. In 2007, the ministry released a set of national standards outlining limits on additive use.

However, the safety of food additives remains a major public concern. For instance, powdered monosodium glutamate (MSG), one of the most widely used flavor enhancers in the world, has been accused of causing health issues including hair loss, amnesia, and even cancer for more than four decades, despite evidence suggesting it is not dangerous to consume in moderation.

Despite the public aversion, sales of food additives continue to grow. A report from Qianzhan Industrial Research Institute estimated the total sales of food additives in 2021 reached over 134 billion yuan, with an annual growth rate of 5 percent. Another report from Huajing Research Institute in 2020 noted that the output of sweeteners in 2020 surpassed 230,000 tons, an increase of 10.5 percent from 2019, due to growing demand for low-calorie sugar substitutes from health-conscious consumers and people with diabetes.

In contrast to the more than 4,000 legal food additives in the US, China has only legalized over 2,300 additives used in food, with just 10 new additives granted approval each year, which Cao Yanping, food and health professor at the Beijing Technology and Business University, believes can help alleviate the concerns of the public. “Ordinary people don’t know how food additives are made and how they get assessed [by the authorities],” says Cao, “so they tend to think, ‘If we have to use [food additives], then could we use less of it?’”

Some experts believe food additives have been unnecessarily demonized in China. Sun Baoguo, member of the Chinese Engineering Academy, noted during a lecture in Guangzhou in 2017 that about 80 percent of respondents in one survey blamed food safety issues on food additives, which Sun thought was misguided. Sun also pointed out legal food additives are often confused for illegal chemicals, like the melamine from China’s 2008 milk powder scandal, and emphasized that whether an additive was harmful depended on the dosage.

Cao agrees, “Everything can be harmful and toxic. You shouldn’t eat too much salt, sugar, oil or even drink too much water.”

Some unscrupulous vendors do use illegal additives to further enhance the flavor of their food and maximize their profits, as Xin regularly exposes in his videos. This also exacerbates public misunderstanding of legal additives. In 2011, China Central Television exposed a brand of steamed wheat bread sold in supermarkets for using tartrazine, a synthetic dye banned from use in flour products, to give the bread an appetizing yellow color. In 2019, the owner of a Zhejiang restaurant was charged for using 1,070mg/kg of aluminum potassium sulfate, over 10 times the legal amount, in making deep-fried dough sticks to enhance the flavor and cut costs. He was sentenced to detention for five months and fined 5,000 yuan.

The deep-rooted public aversion to additives also hurts legitimate businesses. Another food blogger, Liu Song, went viral this August with a video showing how vendors can use a spoonful of evaporated milk to give mutton soup a tantalizing white color that they would otherwise have to boil all night to achieve. Subsequently, a mutton soup restaurant owner on Douyin had to livestream her soup-making process for two days to prove that she boils her soup in the traditional method, after netizens flooded her page with accusations she was faking the color with additives.

In August, an article from the China Food Newspaper, a publication under the China Light Industry Association, criticized Xin for “selling anxiety” and “publicizing illegal methods” with his videos. But Jiang, the health vlogger, believes Xin is in the right for exposing abuses in the food industry and helping raise public awareness of illegal additives. According to Xin himself, his videos have been reported by users many times and Douyin had asked him in September to “improve” his content, after which he decided to delete his account.

Demand for additive-free products is also booming due to health concerns. According to an article from the Beijing News, Lechun, a Beijing-based yogurt brand marketed as containing zero food additives, witnessed its sales reach over 10 million yuan within three years after its establishment in 2014. However, in 2020, the State Administration for Market Regulation drafted a new regulation, which it opened for public feedback, suggesting to ban the use of terms like “zero additives” on food labels as it misleads customers about what food additives are.

Jiang estimates that her food expenses run are more than double those of an average person who doesn’t try to avoid additives, but doesn’t consider it a great hardship. “I don’t buy other stuff like beverages and snacks. I eat better, but not like those who say they eat delicacies,” she says. She believes that in the beginning of the reform period, people in China mostly ate in order to feel full, and accepted that some additives were necessary to preserve food, but these views are changing. “With our current technology we can preserve food without additives, but the costs are higher,” she says. “If our nation supports a zero-additive policy and offers subsidies, then the industry will take responsibility and develop a social conscience.”

Professor Cao, however, points out that “zero additives” doesn’t necessarily make the food better or healthier. He recalls that as a child, his family in Hebei used to make soy sauce in jars without any additives, but this sometimes developed harmful bacteria. “If food doesn’t contain additives, then you won’t know when it goes bad, but if bacteria has grown inside it could cause much more harm [than food additives] to your health,” explains Cao. “The vast majority of food-borne diseases in the world are caused by microbes.”

Cao doesn’t think people can live without additives. “Why do people prefer [store-bought] beverages to homemade juice? If you just make juice at home out of an apple or pear, do you like the taste? Probably not,” he says. “You can’t protest additives at the same time you enjoy the taste it creates. It makes no sense.”

Corrections: An earlier version of the article stated that tartrazine was banned in food, when it is only banned in flour products. The State Administration for Market Regulation only issued a draft of a regulation to ban the words “zero additives” in food packaging; the regulation has not gone into effect at the time of publication.